Home is Where the Art is

Imagining Afghan futures and feminine space with artist Hangama Amiri

Images: Courtesy of the artist

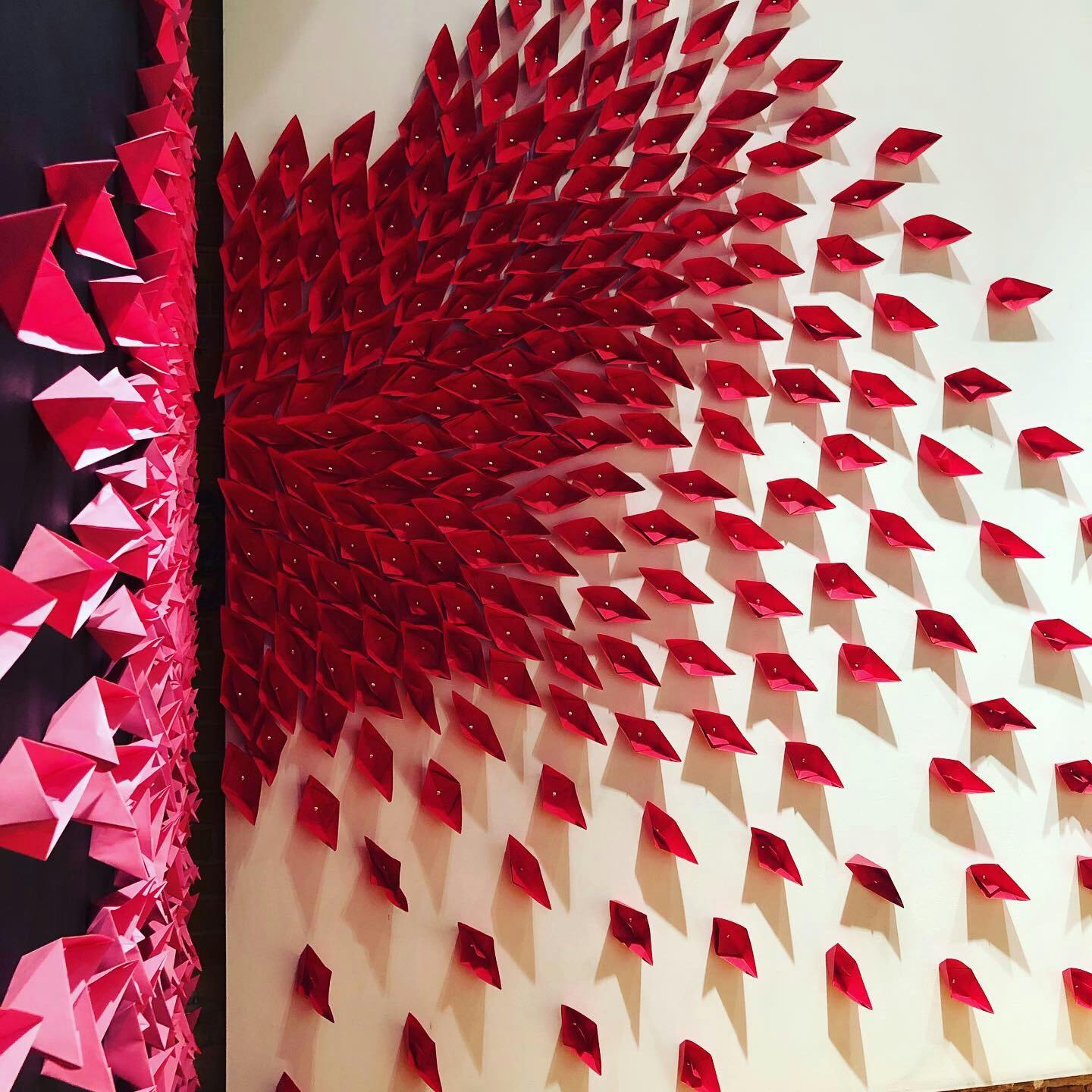

Hangama Amiri, an Afghan-Canadian artist, finds herself at home on the margins and in mobility. She uses fabrics and photographs to weave together memories and materiality as a cross-cultural dialogue. She believes in “using the white walls [of a gallery] to show a slice of colour of [her] reality, as a way of making history.”

There is a calmness in her existence on the margins; the ideas of displacement and misplacement inform her art, as does the inability to choose between belonging or amalgamation.

Amiri has lived in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Tajikistan, before immigrating to Canada, and she distills this mobility into visual narratives of women’s lived experiences in Afghanistan.

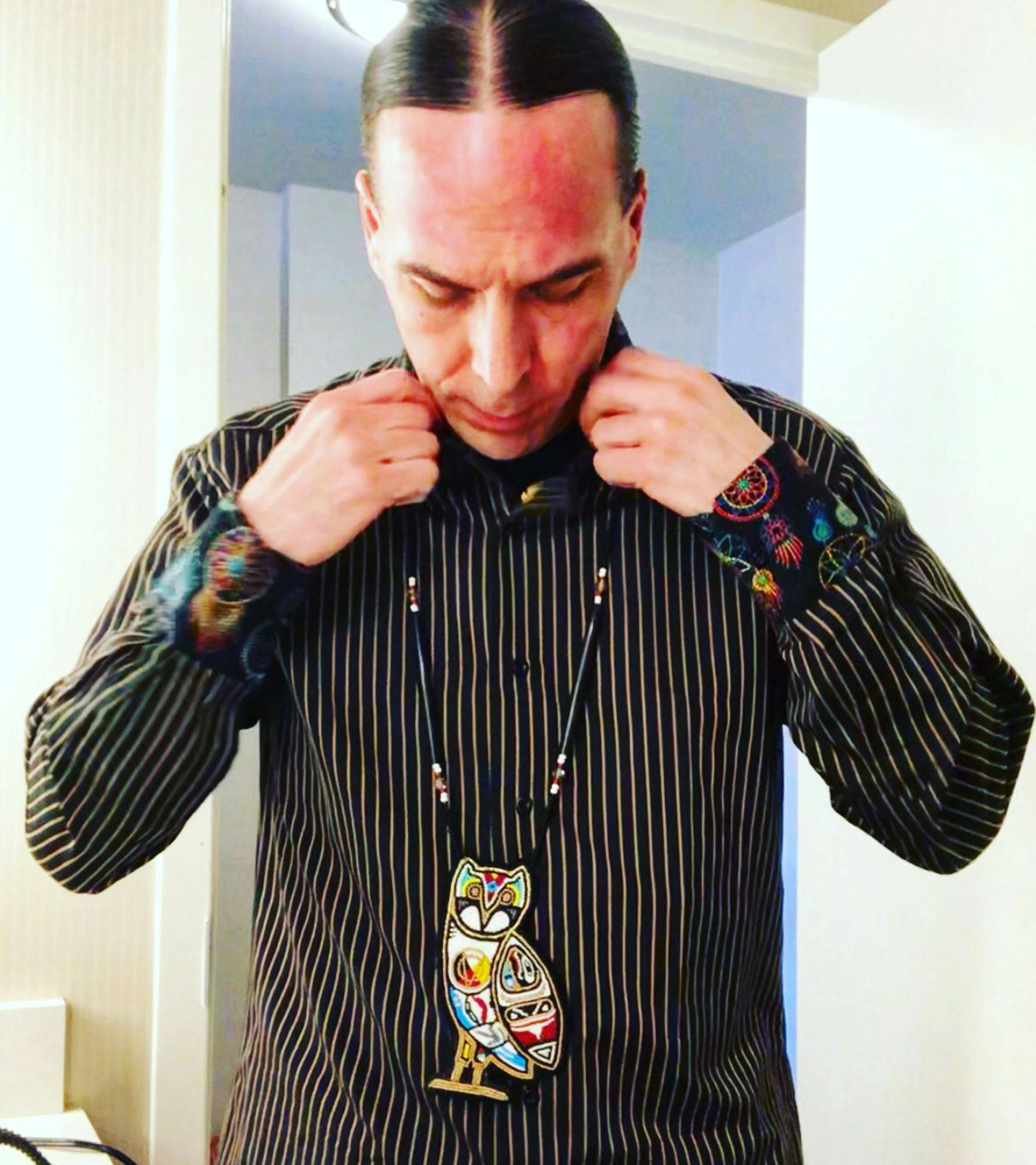

The chaos of the pandemic coincided with political turmoil in Afghanistan, and Amiri experienced “a sentiment of grief,” which she expressed through a self-portrait. In a paradoxical visual, she used the image of a wounded deer, who was cheated and betrayed by a friend to represent Afghanistan’s political crisis.

The pandemic and lockdowns have been a period of self-reflection and longing for ‘home’ ; like many of us Amiri experienced this period as a time of remembrance and reflection about what it means to be away from home and family. This emotional experience has been central to her life as an immigrant; on the idea of home, she says “sometimes one becomes a child who wants it back.” Her art and the narratives she constructs using canvas, textiles, and photographs are an expression of this self-awareness and nostalgia.

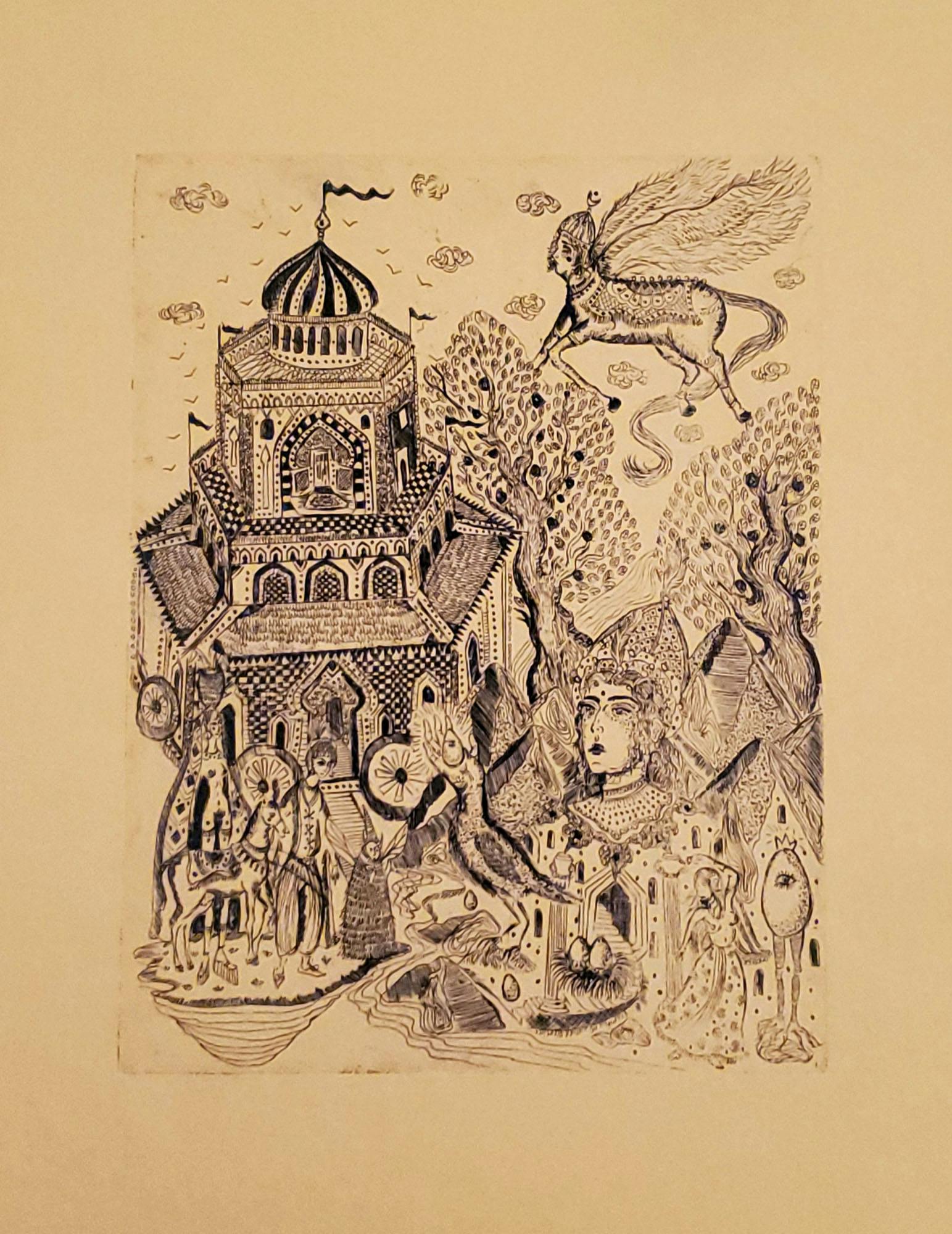

Focusing on diasporic identities and personal feminism, her art is contextualized by memories, war, asylum, loss, and fear, expressed through fantastical images, she creates a visual narrative imbued with both materiality and cultural history.

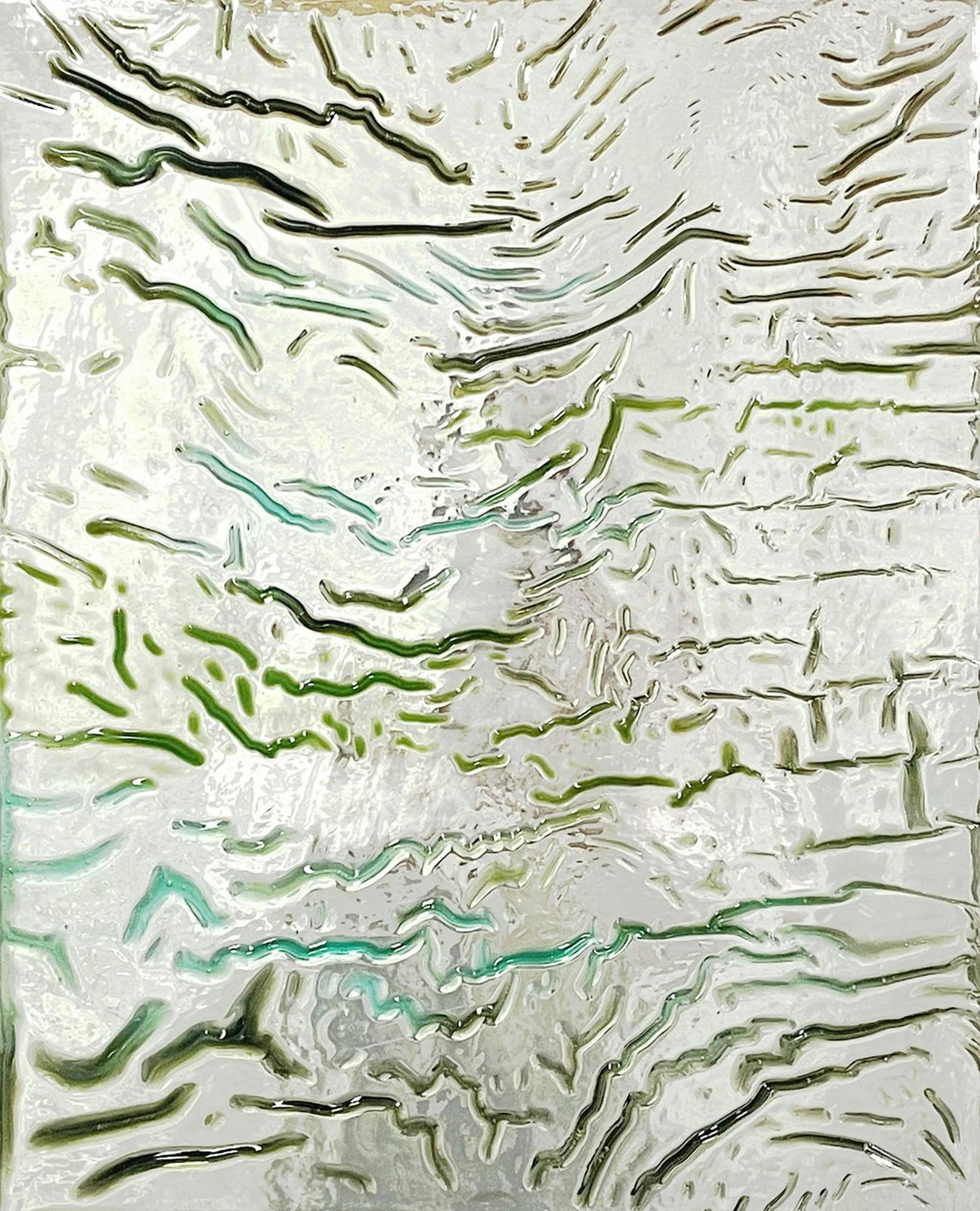

Her use of fabrics, and their attendant textures and compositions, foster a particular aesthetic quality; cultural experiences are woven, entangled and enmeshed. Through this process, metanarratives of Amiri’s story are transmuted, defining her as a person in constant flux.

Amiri’s memories from her time in South Asia serve as a material residue in her art, of lived experiences and conversations with family in Afghanistan. For Amiri “in between-ness is mobility, new ways to express [herself].”

As a storyteller she brings together bazaars, Bollywood, textiles, intimate relationality, dialogue with her subjects, and interaction with mundane objects such as photographs or clothes. Together, these lend a sensorial quality to her compositions; I can almost hear the bustle of the bazaar and rustling of fabrics.

Listening to these images I’m reminded of home as a familiar physical and emotional experience, and the accompanying memories, smells, textures, noise, people, interactions, and language.

Using sites like a military tank, in a desolate location in Afghanistan where lovers meet, away from possibility of communal condemnation but near a symbol of military conflict, Amiri brings her memories and personal politics to life. These images are metaphorical, allegorical, political, personal, cultural, historical, autobiographical and social in a way that the “storyteller is amalgamated and made visible and invisible in the same instance.” Inspired by photographs, memories and conversations, “Bahar, Beauty Parlor” explores the politics of beauty in Afghanistan, dichotomies of private and public life, the visible and invisible.

Amiri’s art is also inspired by an intergenerational conversation, between a past lived by her mother when “Kabul was the Paris of Afghanistan,” and that of Amiri’s generation, where lovers meet on a military tank.

The salon is close to her heart, acting as both the past and possible future. She remembers her mother’s love for nail polish and that her uncle always associated her mother with nail paints; an anecdote sharply pointed at the irony of contemporary Western notions of seclusion associated with Afghani women. This distinct transition in the cultural experience of Kabul between Amiri’s memories and those of her relatives, is made visible in her art as a dialogue with different temporalities.

Amiri’s visual storytelling is an expression of diasporic communities seeking belongingness and comfort (through the familiar) on the margins and in mobility.

As a storyteller who narrates and historicizes memories with longing and hope, Amiri’s art explores the dynamics of gender, socio-cultural norms, interpersonal intimacies, East-West experience, geo-politics and the resilience and futuristic visuality of self and belonging. On the question of taking her art ‘home,’ Amiri says she would like to open a salon in Afghanistan, but this vision has been postponed until it is politically possible. Hope persists in her memories and art.