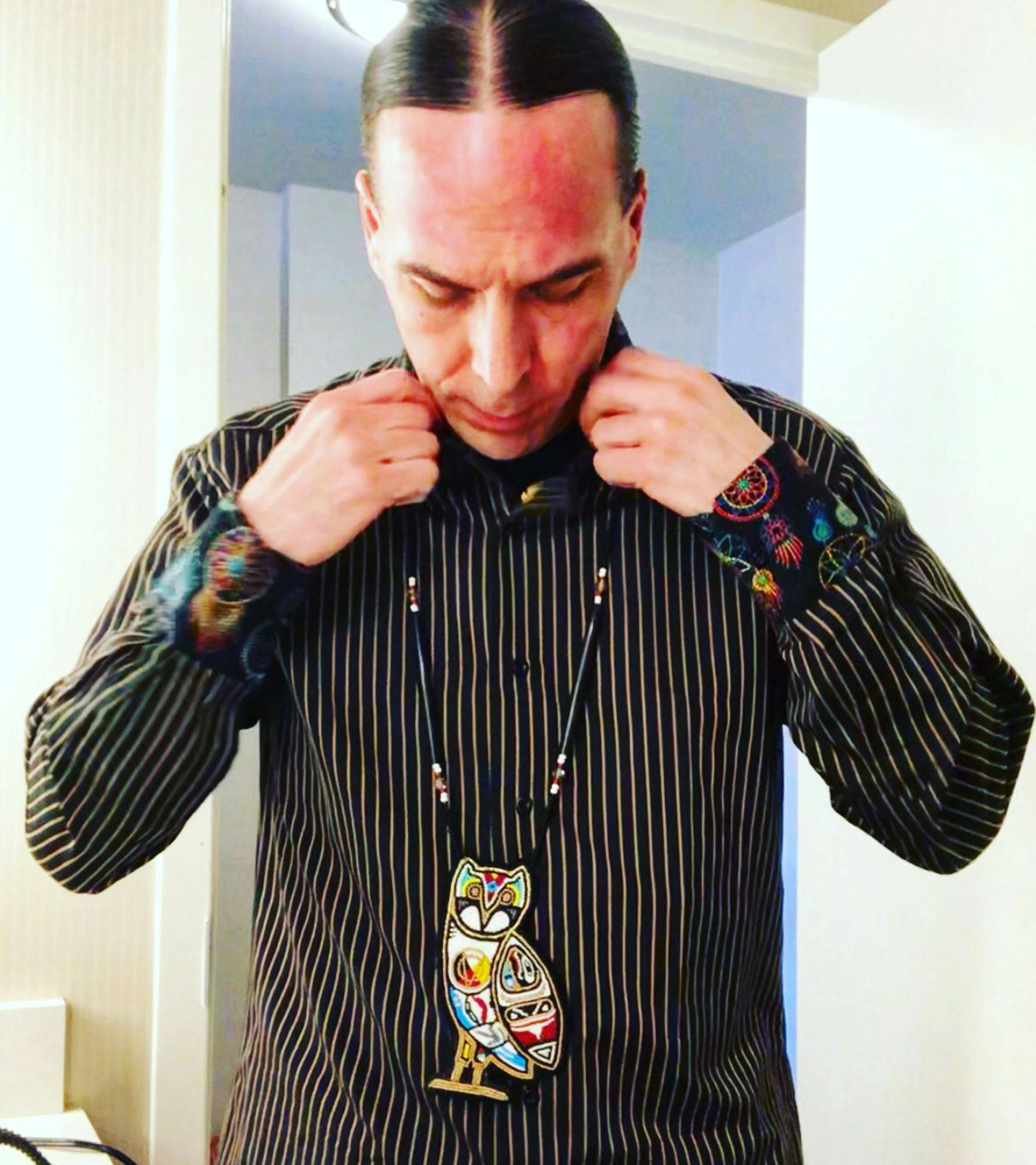

Keep Moving On is a moving recount of a Sikh-Punjabi immigrant family, written by Brampton rapper Amrit Singh, stage name Noyz. Navigating family history via oral retellings and the ephemera of old passports, photos, and music records, the work focuses largely on the relationship between the author and his father, but also their roles within a larger extended diasporic family, and the broader Sikh community.

Singh deftly switches between his own perspective and that of his father, Satnam, to create an engaging narrative that somehow manages to be an adventure novel, thriller, memoir, and historical epic.

His prose is beautifully layered; imbricated throughout with anecdotes as metaphor.

Two of the most vivid examples involve a rural train accident—a clash between India’s agrarian history and it’s industrial ambitions; and a storied ancestor languishing in a Hong Kong prison during WWII for upholding his religious beliefs—a pattern that unfortunately repeats itself for many of the men featured in the book, up to and including Singh.

The events of his various male relatives’ lives, particularly his father, are gripping and prescient in their retelling—the former micro transforms into the present macro.

Early life in Nawan Pind during the Green Revolution (India’s agricultural industrialization reform period), connects forward to the Farmer’s Protests earlier this year, one of the largest strikes in recorded history. Hardships endured during droughts and monsoons give insight into the life conditions that are to be expected as we face climate change on a worldwide scale.

Migrant routes undertaken through Latin America into the US, or wrangled by coyotes through multiple Central Asian countries in a bid to reach the Mediterranean in search of lucrative work as sailors, reflects migrant flow crises presently being faced on multiple continents. Satnam’s seafaring days offer us a window into the intricacies of the global supply chain (including a reference to a blocked Suez Canal), currently under incredible strain from the COVID pandemic.

One of the areas in which the book excels is the author applying his own mental health background (personal and professional) to his relationship with his father.

There’s a scene where the elder Singh is only able to share some of the more intimate details of his life by doing busy work. This interaction- moving in a way that keeps his mind more open via bodily repetition and distraction- while not labelled as such, feels reminiscent of EMDR therapy.

We also get to bear witness to the generational shift; the author struggling to cope mentally and relate these challenges to his family, who find themselves in work, spirituality and art, but in a way that they are unable to share with their children.

While the book is quite rich in scope, there are some observable gaps. There is some interrogation of the role patriarchy plays in Punjabi culture, although the emphasised effects are largely on men, such as the inability to communicate emotionally. This inclusion is important, however the effect on women is notably absent. This is most evident in the passages focused on Singh’s mother’s protracted battle with cancer, that while given a fair amount of coverage in the text, she’s afforded comparatively little interiority. Similar dynamics play out with the grandmother and grandfather.

Singh borrows from Black intellectuals James Baldwin and W.E.B. Dubois, as a way of framing the Sikh-Canadian experience while also referencing this country’s settler-colonial history and national identity as it relates to racialized violence towards Black and Indigenous peoples. However, used in this way, these connections felt to be missed opportunities to explore solidarities and collaboration. This includes the uncritical use of the model minority trope, without recognition of its deployment by the white overculture to tier marginalized communities with Black & Indigenous communities at the bottom.

As a Sikh-Canadian, discussions around land, history and imposed colonial borders in Punjab, should take on a deeper and complicated meaning when we place them alongside the ongoing battles for Indigenous sovereignty in Canada.

With that being said, Keep Moving On remains a vital text towards understanding the Sikh-Canadian experience.

Exposing readers to the world of chain migration, anti-Asian racism, cultural frameworks and beliefs around service and community, as well as the impacts of intergenerational trauma imposed through state violence, and how these communal histories inform present day experiences.

A likely inclusion in future university syllabi, as it sits at the nexus of literature, immigration studies and mental health, Singh has made a compelling entry to the Canadian literary landscape.