Our editor-in-chief Raji Aujla sits down with Alexander Neef, general director for the Canadian Opera Company (now general director of Paris Opera) and artistic director of the Santa Fe Opera Company, and Ravi Jain, the multi-award-winning artistic director from Why Not Theatre, to have an honest conversation about the current state of the arts in Canada.

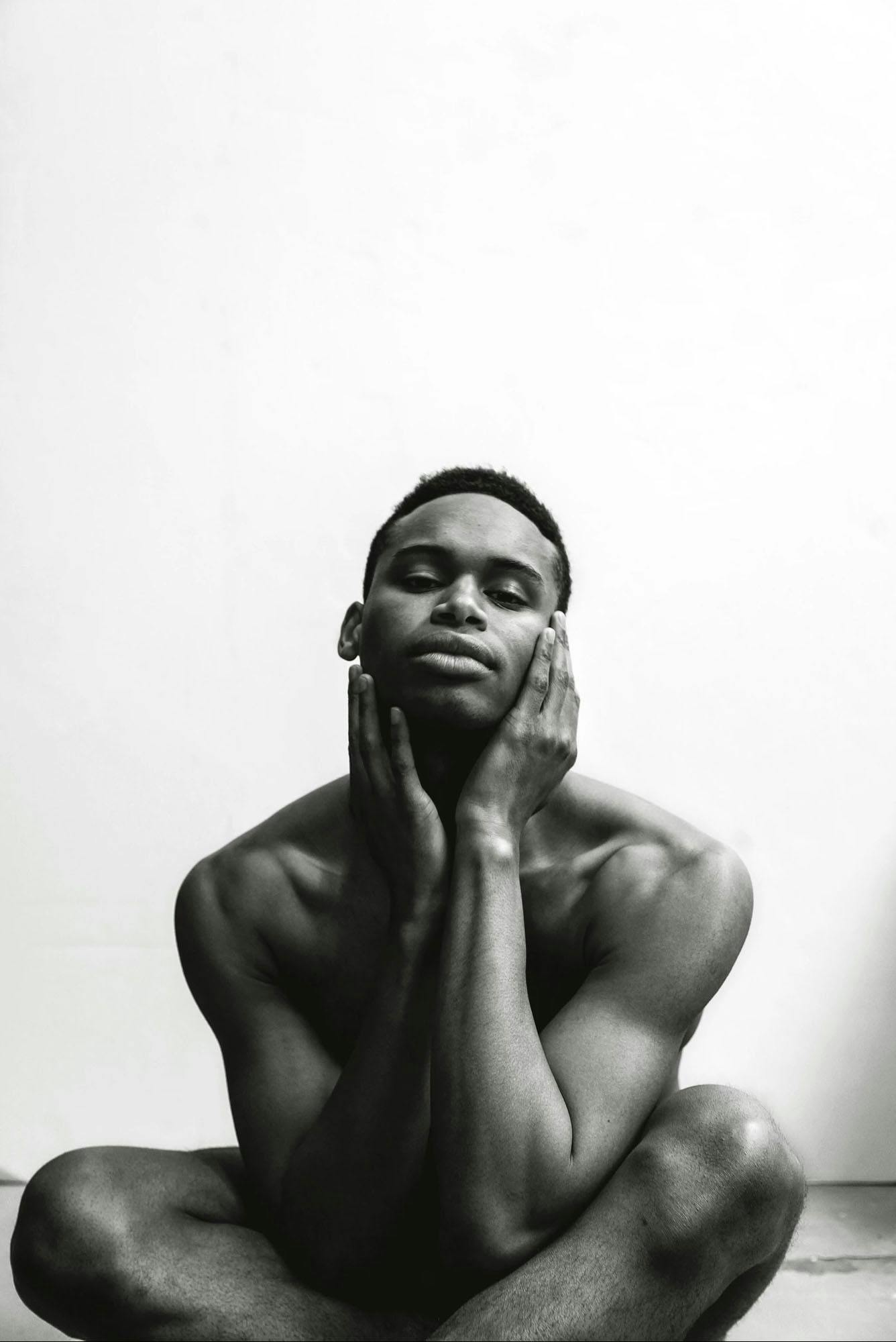

Art is the way we share with one another what it means to be human.

- Diane Ragsdale

Raji

Professor Diane Ragsdale said, “Art is the way we share with one another what it means to be human. Which art, where, by whom, serving whom — all matter greatly in these times.”

Ravi

Historically, we, as a country, have supported sustainability and organizational stability over risk and innovation. That speaks to the kind of art we make and the kind of art that is valued and supported.

Alexander

It becomes more of a general thing even in countries where creativity used to be supported more. Sometimes we start these conversations too late — the scope we set for them starts too late because we never look at who has access to the right training and the right education. We need to open up so much more. I’m not only saying that because it takes organizations such as mine out of the line of fire, but it’s not an invalid point. It’s about the people we hire and work with, but it’s also about the people we can hire and can work with.

Ravi

That’s interesting because in terms of the opera, there’s a specific expertise and training required like there is in ballet. I’ve had conversations with various theatre schools about the history of racism, its influence in the arts, exclusion in the arts and who gets practice. It’s an interesting conversation about who is responsible to ensure that training can be broadened.

Raji

Elaborate on that.

Ravi

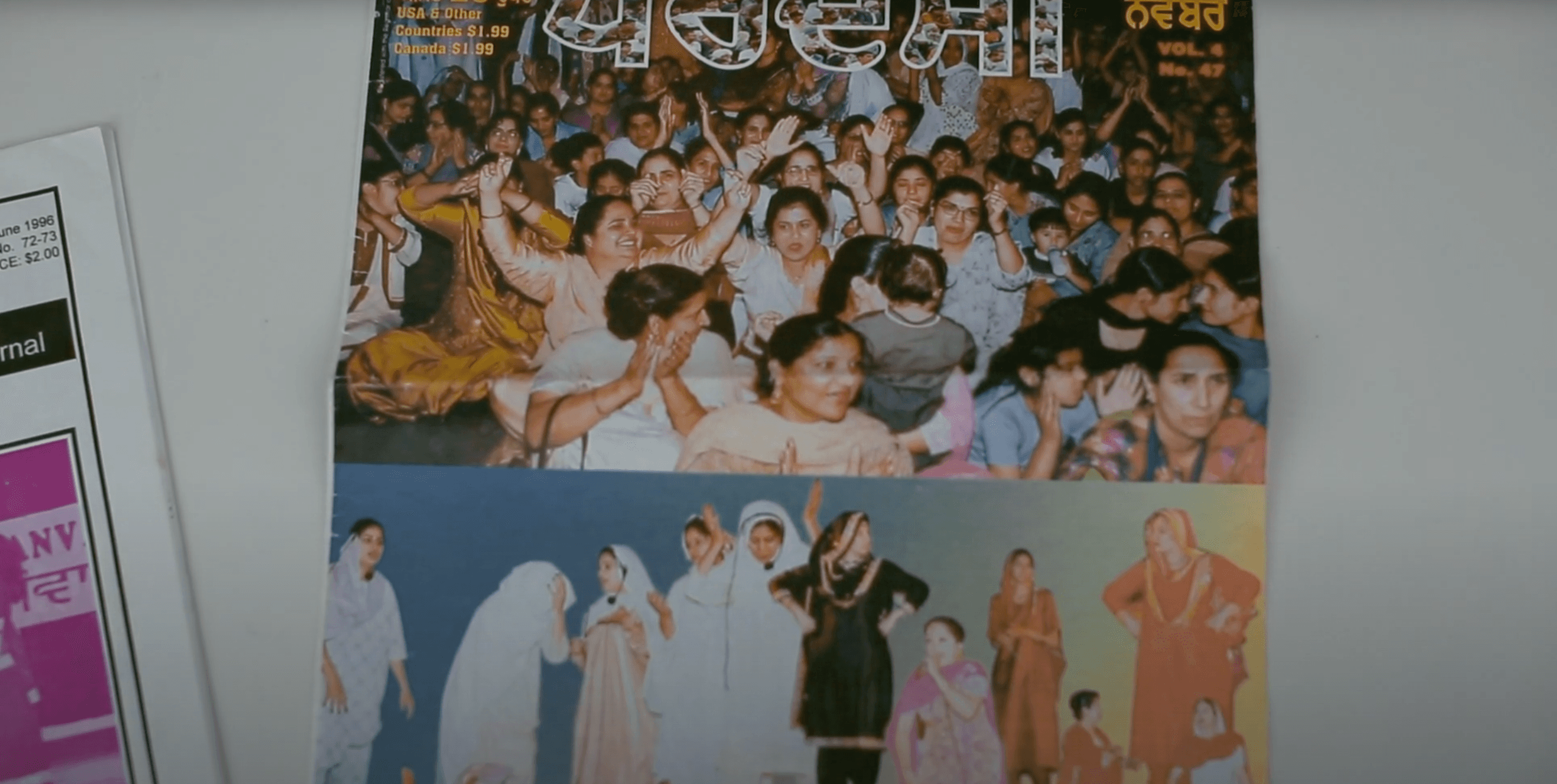

I can speak to it specifically from a Canadian context. The Massey Commission is a good place to start as it still shapes Canada’s arts and culture policy 70 years after its report was released. It assumed that Indigenous culture was not really a thing to be invested in; that it was going to be wiped out anyway so wasn’t deemed to be viable art. It invested a lot into the classics, the opera, ballet — that inheritance from Europe — and over time that became the reaction in the ‘60s and ‘70s to say, instead of doing this European work and American work, let’s do Canadian work.

Then there was an investigation into Canadian voices in the ‘80s: what’s a Canadian story and what is Canadian? What about all of the people of colour, black people, and Indigenous folks, we’re Canadian too. You see an emergence of these cultural groups, but what doesn’t change is the funding to support those groups at the same level as the historic companies. Over time, that separates the world of the arts as high art, low art, community art, and preferential treatment starts to fall more towards higher art forms. That’s where the money is so that’s where we as a society believe art lives.

Alexander

None of this was part of the conversation when I came here [from Germany]. It was completely foreign to my world. Over 12 years, I have had this personal journey of slowly understanding these issues and beginning to discuss how my organization fits into and positions ourselves in this environment. This is an infrastructure that has been built over 70 years. What do we do with that? How do we open it up? How do we provide access? There’s a lot of information on bias and unconscious bias, why we hire certain people and not others. I come back to access to talent. We have the artist program that trains about 10 young Canadian singers, and it’s open to any Canadian every year. We don’t solicit people to apply, but the applications received don’t give an accurate representation of Canadian society. How do we reach them?

I wouldn’t be here today running the COC (Canadian Opera Company) if there hadn’t been free education in Germany. My social background didn’t prepare me to run an opera company or even to be able to acquire the level of education that would’ve allowed me to run anything. The only way I could do that is because my parents didn’t have to worry about how to find money to send me to university. When we talk about the most important equalizer, it’s free education. A true merit-based society is only possible if it has an important component: a high-quality, free education. And not to devalue your point, but we’ve moved on from what the Massey Commission considered valuable for this country in terms of art and our general artistic output.

I wouldn't be here today running the COC if there hadn’t been free education in Germany. When we talk about a true merit based society and the most important equalizer, it's free education.

Ravi

I was speaking with Keith Barrker, artistic director at Native Earth, one of the largest native theatre institutions in Canada, of which there are so few. He’d been on a call with the Canada Council folks to see what’s allocated and to whom, and most Indigenous organizations have a budget of $50,000 or less. How can innovation thrive and communities grow if they’re not given enough water to grow the seeds? How can we create systems that allow more voices at the table to get more resources to be able to function, thrive and create the next artistic movement?

I went to school in Paris and lived there for 2 years, right next to the Bastille. I would go to see new opera that really pushed the art form forward, and a lot of that was coming from Canadians like Robert Lepage. The exclusion of different perspectives and different communities has limited our country’s ability to harness innovation to advance the art form and enrich our culture.

Alexander

The problem we then deal with is that even though the general resources dedicated to culture and the arts from the government have increased greatly, they’re still largely insufficient to create what you described living next to the Bastille. First of all, Paris has been fostered as a centre for creativity for centuries. There’s a critical mass both from the artistic side, and also from the side of the public, to that openness for things that our audiences aren’t as open to receive. They are still grappling with achieving a basic level of familiarity with certain art forms, and the arts in general, which doesn’t make it easier.

The only advantage is when we do one of the most popular operas, many audience members will see that particular opera for the first time. It could be an unconventional and radical interpretation, but it would be their first Carmen. The upside of an audience that is familiar with the repertoire is a greater sense of ownership in the art. Plus the government, I don’t know when you were in Paris, but when I left there 12 years ago, the government subsidy was 65% of the budget, which multiplies your opportunity to take greater risks. The risk aversion big organizations in this country have is because of revenue pressure. The COC is a $40 million-dollar operation and I can only take a calculated risk if I can balance it with the rest of my season. We have a very fragile environment and that leads the whole sector to be conservative.

Raji

There seems to be this cycle of who you’re trying to please, how you’d like to innovate, the limitations that you have and then the government not stepping in to support all of this. Is that what you mean by the “fragile environment?”

Alexander

There’s a strong tendency to do what you already know will work. Sometimes you go to battle for something that you really believe in and sometimes you have to pick which hill you want to die on. There’s a completely untapped audience out there for all of us and we have to figure out how to get in touch with them. Fragile environment or not, they require that effort.

Ravi

Salt-Water Moon by David French is a classic of the Canadian theatre canon. A lot of drama school-trained actors [of colour] were praised for excellent performances during classes and workshops, but never cast in the production. And so when Nina Lee Aquino from Factory Theatre invited me to direct a play, I chose Salt-Water Moon, cast non-white actors, employed “standard” Canadian accents instead of Newfoundland ones, pushing the play closer to today and audiences further away from the same old, same. The older, regular theatregoers saw a new way to look at a story they were familiar with on the page and stage, while an entirely new and younger audience felt invited, seen and reflected in theatre for the first time.

The door was opened for a risk to be taken and it paid off with rave reviews and revenue as we toured the production across the country. The scale is different to what the COC works with, but the thing that drives our company [Why Not Theatre] is creating that space for new possibilities, exploring new ideas and expanding the audience base. We’ve grown to have an operating budget of $3 million with no venue, which is unique in the landscape of independent companies in Canada. What role do we play in risk and innovation, and what role does the COC play with the limited amount of risk that you’re able to take? Are there ways for us to work together that justify the balance sheet, advance the art form, increase diverse voices at the table and utilize our collective expertise effectively?

What role do we play in risk and innovation, and what role does the COC play with the limited amount of risk that you’re able to take? Are there ways for us to work together that justify the balance sheet, advance the art form, increase diverse voices at the table and utilize our collective expertise effectively?

Alexander

It’s not too late for me to open the door for that. You’ve given me a lot to think about. It’s interesting, what we were supposed to be doing right now [during the coronavirus pandemic] was a revival of Aida. We premiered it in 2010, at the beginning of my time at the COC. The director Tim Albery and I decided early on to strip down Aida’s typical pageantry to focus on the tale’s emotional heart. We didn’t want people going into an imaginary Egypt for some feel-good idea of Aida. We wanted to focus on what the piece was really about: human relations. In opera, people thought it was still okay to paint faces back then too, but we made the decision not to do any of that. This was before anybody was talking about political correctness. A good part of my audience got really angry about the show. They felt cheated out of “their Aida experience” because we didn’t give them what they thought Aida should be about. However, there were others who said this was an eye-opener, that opera wasn’t stuffy and could actually be relevant and about them. That was my first moment of risk-taking at the COC, and I felt it paid off because nobody who saw that show forgot about it.

Indifference is our biggest enemy. Ideally, people are supposed to love what we do, but I prefer they hate it than be indifferent to it.

Ravi

To contemporize something and make it relevant for an audience today in that context is challenging.

Alexander

It is, but I’ve come to simplify my thinking about it. Things become classics for various reasons. The whole trajectory is saying to people,

yes, we do Mozart, Verdi, Beethoven, Wagner… but we do them as 21st century people for a 21st century audience. We’re not some time travelling company that does Shakespeare by transporting you back to Elizabethan England. We do these works because we still find in them something that moves us, not only as audiences but also as artists.

Raji

Who do you think you’re responsible to? Are you looking at what you think the audience needs or what your board directors would prefer to see?

Ravi

We’re always building work for the multi-ethnic audience of today and tomorrow. Our responsibility is to not only produce groundbreaking and relevant work for them, but also ensuring they’re not priced out when it comes to tickets being accessible and affordable too.

Alexander

My responsibility is to ensure the place doesn’t go bust. I don’t feel that the board at the COC controls the programming. Of course, some of them are very opinionated and there can be creative conflict between us at times, but there are certain things that I would not consider up for compromise. Every artistic leader has to tread that line because this is about art, culture and business, not personal satisfaction. The board made a decision to hire me to be a steward of this company and I take that very seriously.

Raji

How can we innovate in the arts when we’re programming so much in advance? We have to have a certain level of foresight but in the case of a global pandemic we could not have prepared for, how do we produce something quickly to respond to a need right now?

Alexander

There’s a great play from 2500 years ago called Oedipus Rex, where the city of Thebes is struck by a plague, the citizens are dying and no one knows how to put an end to it…

Raji

But you couldn’t produce something like that at short notice.

Alexander

You could. If it was possible to rehearse right now, we could have Oedipus Rex ready for performance in four-to-six weeks. When it comes to reacting to day-to-day politics or current events, it’s different for art forms such as cabaret or stand-up comedy, but for theatre, it can miss the point. We want to do things that resonate with different people and different situations in different ways over time.

Raji

How do we make sure our artistic productions respond to the needs of a generation that consumes art differently? There are case studies in the private sector, Mejuri and Glossier, who built a digital culture and strategy first, as that’s where consumers are. From there, they opened a bricks and mortar. Here, we have arts with bricks and mortar, but no engagement. Arts have a hard time innovating because they’re not viewing themselves as tech-focused companies, optimizing the power of analytics to learn about consumer behaviour.

Recently, the New York-based This Is Not A Theatre Company staged an immersive play. They brought an experience to your own home that was experimental, multi-sensory and participatory theatre. The product infrastructure was every day technology — a smartphone and social media — curated into an experience. There was no production necessary, just organization. How can our arts organizations utilize technology more efficiently and effectively?

Ravi

A major part of the process that we need to figure out is what the translation of our analogue art form to a digital platform looks like. While there are those individuals and institutions that are already way ahead, not everyone is equipped to make that transition at the present time. The audience in this digital world is actually everyone. Platforms exist where we can broadcast live and direct to 20,000+ people instantly. That’s a fucking arena. I’ve never had that capability before. You could whip up a sketch that responds to things immediately, but speaking for performance art and specifically theatre, it requires meaningful time, thought and process so that it will be impactful.

Alexander

By nature, what we do is analogue. Either we are not proud enough of that, or there’s insecurity because we are led to believe everything needs to be interactive. Digital engagement is a means to an end to get people back into the theatre. Everybody is doing something right now to stay connected with their audience because we can’t give them the real thing, which is that gathering of people in a space inviting them to go through an experience together. That is irreplaceable by anything digital and we need to hold onto that. We are one of the few spaces where that is still desired and required in a world that’s moving fast, product is pre-packaged and people don’t want to think too much. The difference between a digital experience that you watch on your device and being in the theatre is that we invite people to be their own camera in the theatre.

Ravi

A younger audience may be integrated with technology in a way that our generation might not be, but that doesn’t mean they don’t engage with the arts. Again, we communicate and interact with groups of people that have been excluded over time. We have to find the right language and relevant work that illuminates for them what is unique about this way of engaging your time.

Raji

Digital does not need to be the answer. I agree with both of you about time being an important factor in the creative process. And being in a physical space is my preferred way of consuming art. Alexander spoke of a fragile environment. What can be done to help strengthen it?

Ravi

The fragility in our environment is the working structure, in particular for the freelance artist. In this environment of entrepreneurship, there are many self-employed artists that need help with building a sustainable career in the arts. Generator T.O. is one great resource for them. They’re an organization that mentor, teach and expand the skills, tools and competencies of independent artists and producers.

As an arts community, our duty is to serve artists and serve audiences.

As we can’t serve audiences in a physical space right now, we should be focusing our time being of service to artists, especially those facing pervasive, systemic barriers in the arts rooted in racial and gender bias and stereotypes. Our crew are currently helping young women of colour get access to mentors, people and institutions all around the world. That’s one effective use of the Zoom video-conferencing app as we all navigate the pandemic. We have to develop our collective skills and strengths because no matter what happens when we come back; those barriers will still continue to be there. So if we can’t serve audiences right now, maybe we can fix our sector — address the challenges and systemic barriers in our sector and get to work on them so that when we come out of this, we emerge stronger.

Alexander

From our perspective, I’m looking at the number of people I feel responsible for in terms of maintaining their livelihoods. It goes in different circles from the core staff, administrative staff, and members of the orchestra and stage crew, along with others associated with temporary contracts. That’s an ecosystem of hundreds of people we work with throughout the year that depend on us having activity. My job is to not only produce art but also to find enough money to pay everybody. People rarely think of leaders of large organizations that way. If 20% of my day is artistic, it’s a good day. I wish we had stronger organizations in different sizes so that we could sustain the general environment because you’d pass that institutional strength on to others.

Ravi

Where do the arts make a societal impact in terms of your reference to social justice?

Alexander

We spoke about access to free education and how that is the only effective equalizer in many ways. Artistic practice and arts education ties into that. It’s great to have free access to learning math, languages, physics and biology but learning artistic practice allows people to think independently. The most important thing about interacting with the arts is that it builds transferable skills, individualism and creativity.

Look at Albert Einstein; he was a passionate musician who played the violin throughout his life. It’s important not to negate that. Scientific practice and artistic practice are closely linked and the brilliance of a scientist comes very often from creativity that was trained in artistic domains. Our society has trouble understanding that and regulates the arts to this corner of leisure and entertainment when the essence of it is building up those transferable skills, creativity and individualism. We need that now more than ever.

Raji

What do you think are the long-term effects of arts education and how it carries itself out in society?

Alexander

We talk a lot about future leaders, but we’re not really training them in the art of leadership. We don’t allow people to have free access to artistic practice. What develops and builds leaders is the ability to be a creative individual, not following the mold.

Ravi

One of the most important things artists do well is listen. We listen to what’s going on in society and then put out a vision of the world that we aspire to achieve. Whether it’s a hardcore political piece or a light comedy, that message is still there. The arts is about activating people to think differently, to dream possible worlds, to dream alternative visions of existence, and to see the world reflected in a way that provokes them to want to make change and build a better world.

Alexander

It’s important that we also listen to each other. The ability to agree and disagree is a discourse that needs to be at the same level. Disaster doesn’t have to strike if we don’t share the same opinion. We can talk about it. That is the opposite of the polarization we’re seeing at the moment where some people think if they don’t agree on everything, then there is nothing to talk about. This idea that my truth is the only truth is crazy. In a way, what the arts teach us is that there is no truth.

Ravi

Or that there’s many truths.

Raji

Maybe that’s the one truth, that there are many truths.

Alexander

If we can accept the fact there are many truths, there has to be a framework for that that makes for a more equal society.

Raji

How can this awareness, building education and empathy within the arts, lend itself to bridging some of the barriers that the sector is faced with?

Alexander

A part of the issue when you’re fragile is that you’re less likely to share. A silo mentality can form whereby you only concern yourself with your turf, your audience, your donors and your art form. This mentality reduces our capacity to make major progress. Sharing in a fragile environment might seem a difficult thing to do, but we have to learn to do it. The moment we speak as a sector instead of as individual organizations is when we gain more strength, not only with government but also in our communities, with our donors and with our audiences.

Ravi

In the smaller communities and organizations, sharing is a big part of how we survived. I’ve heard the higher up you go, the more siloed things become. We created collaborative producing models that brought together small pools of money to make big pools of money so that everyone benefits. In terms of coming together, one thing we may lack is what the shared analysis of the problem is. We may not have similar thoughts as to why things are the way they are and why inequities exist [within the sector]. If we can all come together and recognize where we’re the same — which is that we all have the same problem right now in that nobody can access an audience — there are many differences where we need to understand how we’re not the same. And that’s not in a negative way. For example, the three of us are very different people because of race, gender and sexual orientation. There are many things that make our experiences in life different, yet here we are with a shared passion for the arts. Those differences are significant and important to create a healthier ecosystem, society and art sector. But you just can’t have a conversation without addressing those inequities because they continue to play out even in the recovering of this pandemic. Certain organizations can be on the phone with ministers and heads of major companies and others can’t. How do we figure out a way to recognize those privileges and create a more levelled playing field? Of course there are those that don’t care about those things, and that’s fine. We don’t all have to have the same fight.

Alexander

In many ways, we don’t. But in the end, we’re working towards a common goal. That might sound idealistic because if push comes to shove, you’re going to take care of your organization first. But what I’ve learned over my time is that when you open up and share resources, it benefits the whole [sector]. We’ve played a small role in creating a more active opera sector in Toronto by sharing basic resources from allowing staff to answer questions from independent companies about government advocacy to writing your first grant. For a couple of years, we had a company-in-residence with Against the Grain Theatre (AtG). We gave them an office, computers, paid their phone bill and gave them access to the resources of a bigger company. We were separated by one floor in our building, so if AtG needed anything, they just had to come down. Even though what we did in terms of monetary compensation was rather insignificant, it allowed them to develop and grow. People questioned me about my decision to help build our own competitor. I’m of the opinion that the more people that like the opera in Toronto, the more people will end up at the COC.

Ravi

It’s amazing what kind of impact a small contribution can have. We went from zero to $175,000 from the Canada Council and that changed our lives. It allowed us to grow into an institution.

Alexander

It creates a much bigger outreach platform for the art. And I should be totally committed to that. There are only so many people, even with the best efforts, that I will ever be able to reach. If we can help other companies to reach more people, we build a critical mass for opera and the arts.

Ravi

You’ve come from Europe and been at the COC for 12 years now. Your next move is as general director of Opéra national de Paris in 2021. Is there more organizational renewal in Europe?

Alexander

Change in leadership for most organizations occurs every ten years. People think that is a good time to get a project done and then someone else comes in on the bedrock of solid organization. Institutions think of themselves as things that need renewal. However, it’s taken me twenty years to build the relationships that I needed to make things happen. That’s why boards don’t really want change because our organizations are so uniquely identified with their leaders and there’s no separation from that. We all have this urge to keep what’s working — rather than thinking long term about the future — which stalls the renewal of the sector. In Europe, changing leadership is a natural and necessary evolution rather than an unwelcome event.

Raji

Why are people so afraid of change in Canada?

Alexander

It’s seen as something that makes a company more fragile. In my case, there may have been a preference for me to stay and continue the project. However, if the transition is managed the right way, it’s a great opportunity for the COC.

Raji

The risk aversion is high in Canadian arts. It can be counter-productive to have a board consisting mainly of businessmen whose forte is solely the bottom line as you need to manage risk and innovation for the creative industries to grow. How are they governing for cultural growth and the legacies of our arts organizations?

Alexander

We keep repeating to ourselves that we have to be businesses, and in some ways, that’s not wrong. I think accountability, caring for resources and not wasting them is important everywhere but I’m not sure if that makes us a business.

Raji

Business literacy is important, but diversification on the board is equally important. Having inclusive representation made up of diverse perspectives and expertise, such as artistic directors and multidisciplinary creatives, would be a competitive advantage. You spoke of education in recognizing that art is a daily part of life. How do you advocate more for the arts to the public?

Alexander

The one thing that the arts do is build identity. It’s the only thing that lasts. I go back to Greek tragedies from two thousand years ago. It boggles your mind how they still resonate. These are what built Athens and Greek identity all those years ago. They created this art that was shared with the community. Nobody remembers who was running Athens in those days, but those poets are more famous than any leader today. I think that should teach us a lesson.

Raji

For nation states, it’s easier to build a shared consciousness on what identity in arts is. It’s harder in Canada, where it’s multicultural.

Alexander

But it should not be impossible. In countries like Canada, we’ve never really tried.

Raji

Multiculturalism has become our identity, but only at the surface level. If you dig deeper, you realize the truth of how much our cultural identity, as reported in the media, is the identity of colonial Canada. The banner of multiculturalism hides the real truths about Indigenous cultural genocide, disproportionate crime against people of colour, inaccessibility to clean waters… you start seeing that multiculturalism isn’t a shared definition. How then do we build a collective identity that is agreed upon?

Alexander

It’s going to take political will and a genuine desire for unification. Unfortunately, it’s easier to play people against each other than play for each other. And in our dynamic, we mostly care about how we secure re-election.

Ravi

If you had a variety of artistic organizations above $10 million dollars, you would see a change in the field of representation. Imagine there was a smaller opera company that was dedicated to Iranian dance or Chinese opera, had a building downtown and worked in partnership with the COC. You would see a different voice represented. We have a desire to embrace multiculturalism with words, however, the actions fail to amplify the range of voices and therefore it’s hard to hear them. It’s like giving someone a tiny speaker and microphone at a big concert while the next person has a huge surround sound system. Who do you think is getting heard?

Alexander

I would love to see that kind of space, but simply do not have a dollar to invest in it because of risk aversion. You have to have capital and a specific mandate to do certain things. We have institutional strength. Rather than try to build from scratch, which will take another 50 years, how do we connect that with the art form that you already have the expertise and experience to do, not have white people do South Asian opera but to create that space within your organization; put those in charge who know what they’re talking about, allow them to emancipate themselves and take up more room. People would then look at us as not only producers of western opera, but as a home of all kinds of musical traditions.

Raji

Yes. The one thing I would push back on is I’ve been in that precarious situation where it felt like I was employed because I checked off so many boxes: command of communication, check; South Asian, check; woman, check; millennial, check. And then to be given a broad mission such as “attract, expand and enhance diverse audiences” was a tall order for the one person of colour to fulfill. It’s a lot of pressure to accomplish so much with a singular mandate that, if not fully achieved — because it’s a lot for one team, let alone one person — sets a bad example to risk employing young women of colour to solve centuries of colonial misconduct. Without a system or structure in place to support and implement diversity strategies, it’s performative and will not succeed.

Alexander

I completely agree.

Raji

The requirement from an institution is the need to help foster, nurture and incubate that mandate; it’s a dual responsibility. That third party you bring on board — such as an artistic director, consultant or publication — works in harmony more effectively when everyone is aware of all the barriers and joins forces to confront them.

Alexander

I think Ravi and I should have columns in this magazine because we’ve only really scratched the surface.