Spaces for Hesitation

On language, discomfort, and the opportunities for solidarities in the colonized state

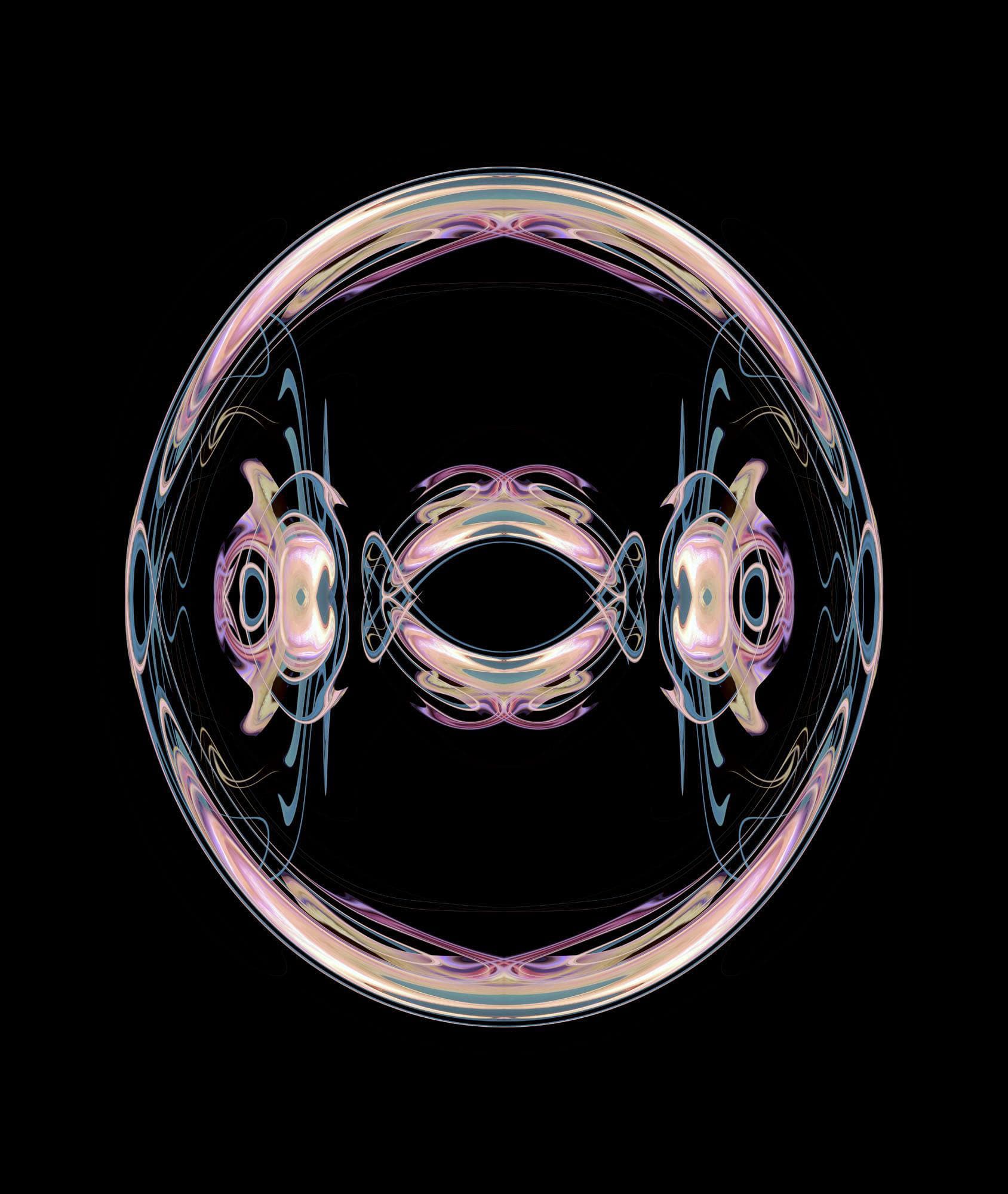

Kosisochukwu Nnebe, “I want you to know that I am hiding

something from you / since what I might be is uncontainable,”

2019

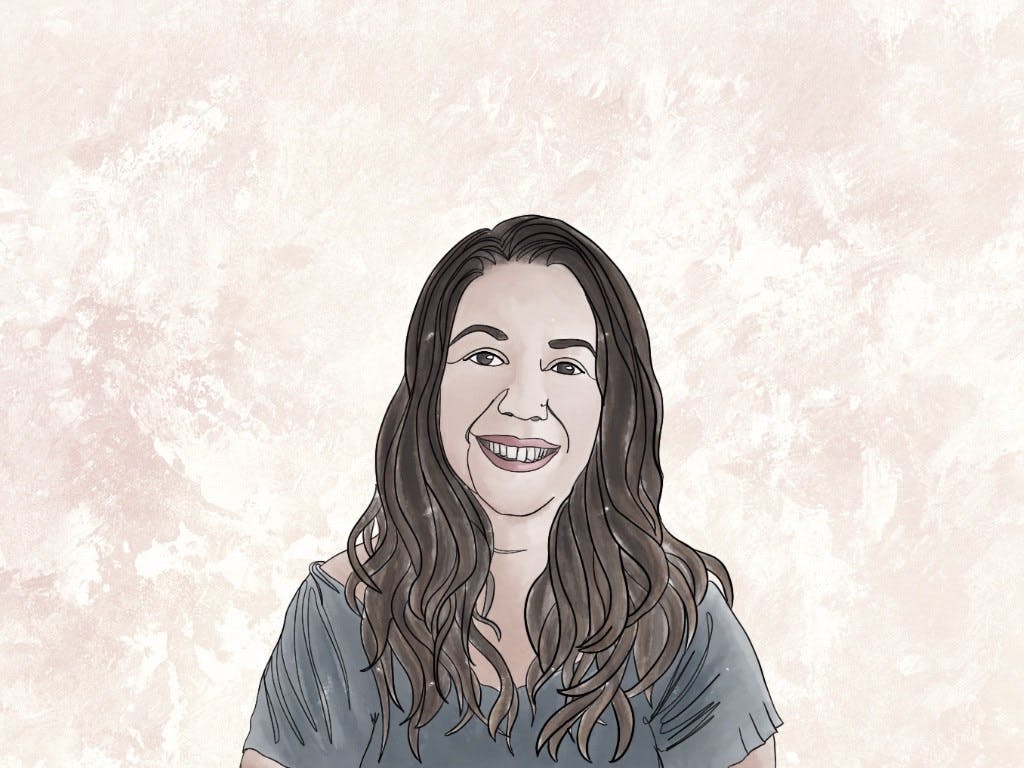

Meghan

Kosisochukwu

Meghan

We’re talking about silence in this issue—the various ways in which it is felt, embodied, mobilized, and politicized. Your work mentions hesitation as a generative form of affect. Hesitation and silence are so often intertwined.

Can you speak to how hesitation lives in your practice?

What does it mean to you?

Kosisochukwu

My interest in hesitation as a form of affect comes from my exploration and use of phenomenology, and specifically Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s approach to phenomenology, within my art practice. In his take on the study of lived experience, Merleau-Ponty is particularly interested in the notion of sedimentation, which speaks to the way in which particular forms of perception become naturalised. Contemporary feminist philosphers such as Alia Al-Saji and Helen Ngo have taken on this line of thinking and deepened it in innovative ways that trouble the naturalized perception of race. For them, creating space for hesitation in how we understand and perceive race creates an interstice, an opportunity to trouble the process of racialization altogether, to re-think race and how we understand it.

I’ve been interested in fostering hesitation in my practice, creating works that aim to create and play on moments of hesitation. A prime example is my two-part 2019 installation “I want you to know that I am hiding something from you / since what I might be is uncontainable”. The first piece of the installation was conceived of as a game of hide-and-seek that the audience was unwittingly brought into—invited to find a representation of me that was hidden in the room.

The work played on the assumption that the audience would navigate the room in a number of different ways and that the varying levels of involvement would yield different experiences. One option was for an audience member to enter, become confused and bored by the installation and leave. The other would be for the audience member to be equally confused but attempt to better understand the work by walking up close to the red banners on the wall and spending more time in the space, gauging how best to experience it. The final option would be to come in, hesitate, spend time in the space, and finally step onto the podium—which was fashioned after a slave auction block—and look through the red plexiglas at the banner. This action would enable them to see hidden images that could only be viewed from that particular position in the space. Hesitation is present in all three options, but it is only through sitting with it, pushing past it and engaging with the work that one is truly able to experience the installation.

The first piece of the installation, “I want you to know that I am hiding something from you” was conceived as a game of hide-and-seek that the audience was unwittingly brought into...

Kosisochukwu Nnebe, “I want you to know that I am hiding

something from you / since what I might be is uncontainable,”

2019

Meghan

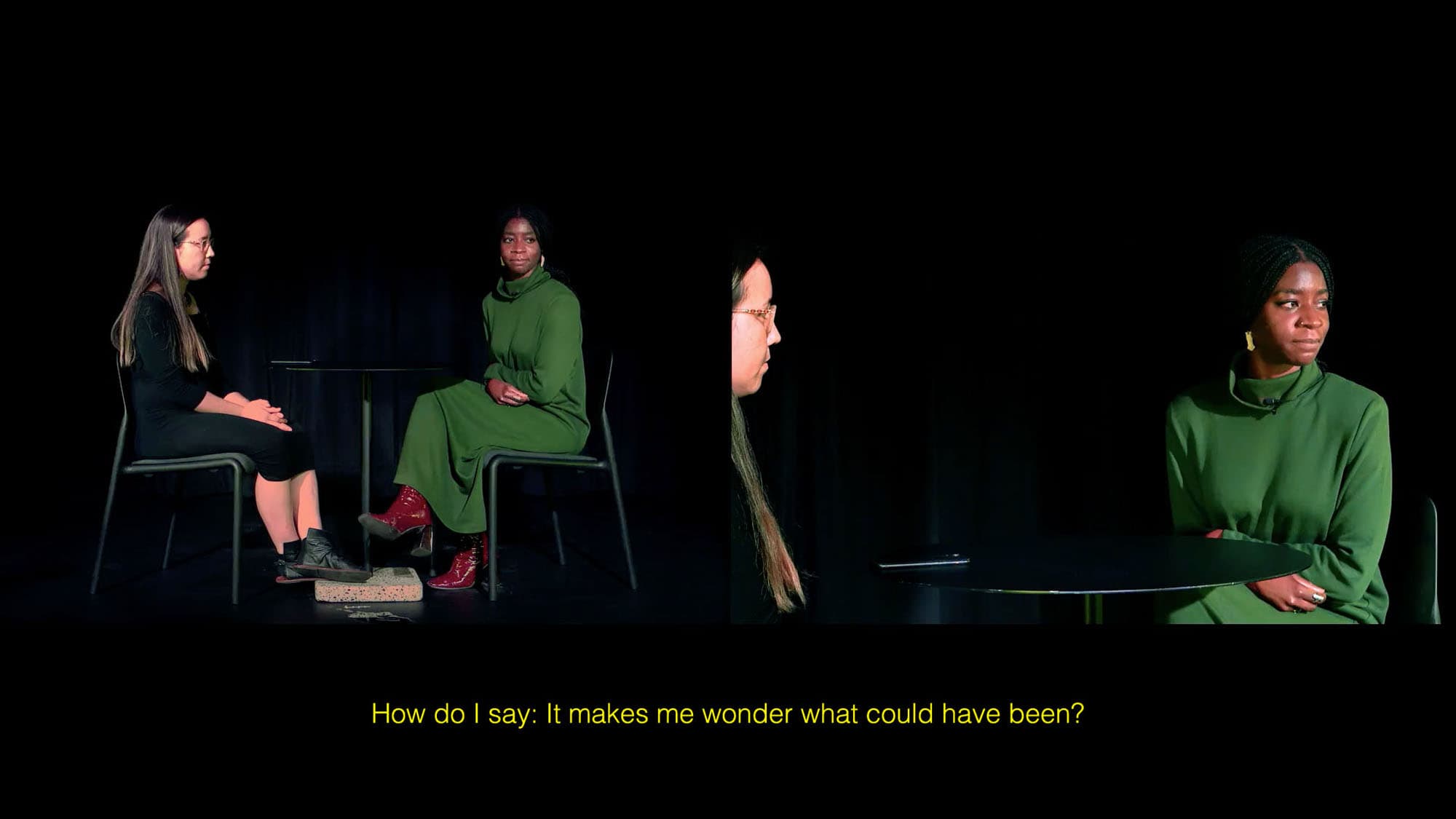

Watching “The ancestors are meeting because we have met,” it seemed as though time, silence, and hesitation created these multi-dimensional pathways for relationship. Can you speak to what you felt in those moments of listening and communicating?

Kosisochukwu

I love this question, and appreciate the opportunity to go back to the work, which was created in collaboration with Katherine Takpannie, an Ottawa based Inuk artist and dear friend of mine, in a way that touches on elements of it I’m only coming to see in hindsight. In a way, there are aspects of how this work would speak to and draw attention to hesitation as a generative form of affect that I had envisioned when it was first conceptualized.

I wanted the moments of hesitation when we struggled to find the words to say in our native tongues – struggled even to repeat the translations shared with us by our parents – to speak not only to the colonial violence that has deprived us of our ability to know our mother tongues, to speak them fluently; I wanted those moments of hesitation to also point to an opening, a possibility of making the world anew by reclaiming these languages that have resisted destruction, that were never rendered obsolete and remain ours to learn and breathe life into once more.

What surprised me, however, was my own discomfort with silence, my tendency to jump ahead and attempt to fill empty space with words. I see this, in particular, in contrast with Katherine, a difference, I believe, that belies cultural difference in a way that is so subtle at times but became readily apparent to me in re-watching the scenes. I know much of it can be chalked up to nerves—we were filming in front of a crew, so it was actually quite nerve-wracking at times—but part of me wishes I had slowed down a bit more. That I had sat in those moments of silence and contemplation for just a second longer. That I had let the words and translations sit on my tongue for longer, let them melt and savoured them as they were—foreign but familiar, new and ancestral. I wish I had listened more intently to Katherine and her parental figure as they spoke Inuktitut and thought through the differences between it and Igbo. There are so many things I have left to think about, including around silence—I know I am only just beginning to parse through what this all means.

I wish I had listened more intently...as they spoke Inuktitut and thought through the differences between it and Igbo

Image: Kosisochukwu Nnebe (in collaboration with Katherine Takpannie),

“Ndi nna nnanyi na ezuko maka na anyi zukoro / Imaaqai,

suvulivut katittut katisimagannuk / The ancestors are meeting

because we have met,” 2021

Meghan

Your work on the relationship between language and imperialism. Can you tell me more about this exploration?

Kosisochukwu

This exploration is very much an outgrowth of my Masters research into Black-Indigenous solidarities, which itself stems from work I did as a policy analyst with the Canadian federal government leading engagement with Indigenous communities on the development of a national food policy from 2017-2019. That work forced me to engage with the question of what it means to be a Black woman on these lands—for me, specifically, the uncedeed and traditional territories of the Algonquin nation—but it also brought me to question the impacts of colonialism and imperialism in my own connection to the land of my ancestors—to our cosmologies and distinct ways of knowing and being.

As I learned more about Indigenous worldviews first through my work as a policy analyst and then through my work curating They Forgot That We Were Seeds, an exhibition bringing together eight Black and Indigenous women artists around the theme of food—I began to feel a sense of loss and a concomitant desire for reconnection. Through a focus group for my masters dissertation, language emerged as that thing that not only allows us to connect with ancestral knowledge but is what holds it, keeps it alive. The work of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o then became influential in helping me understand the ways in which language has been used as a tool of imperialism, fostering a “subjugation of the spirit” that was meant to go alongside the physical subjugation ensured by other forms of violence. In many ways I became fascinated with the idea of language as a kind of archive and cultural carrier that bears the mark of encounters between different cultural groups and nations, be they friendly or violent, becoming both the wound and the bridge for many colonised peoples.

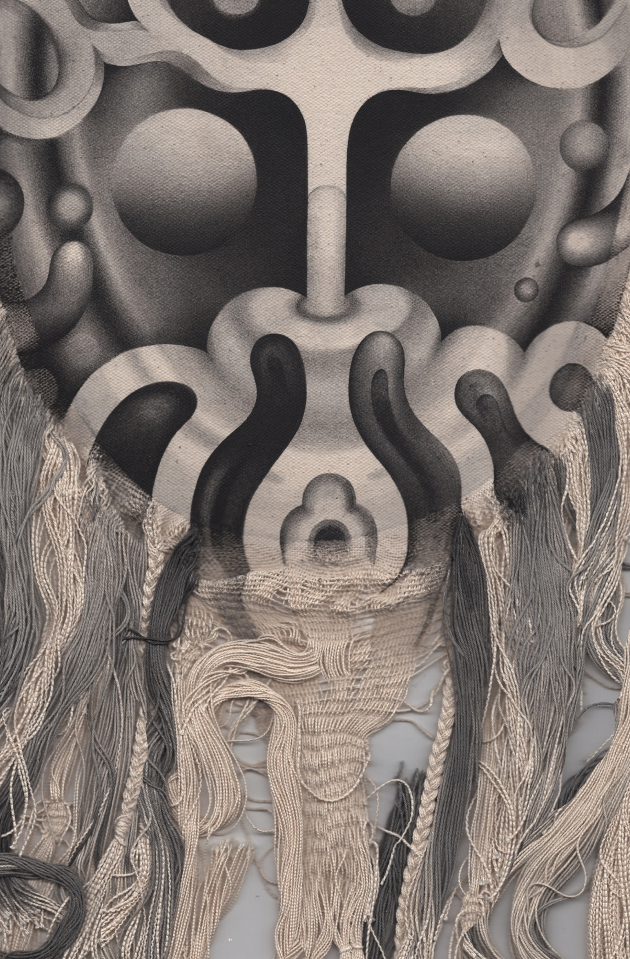

Image: Katherine Takpannie, Katiniakusii, 2020

I became fascinated with the idea of language as a kind of archive and cultural carrier... becoming both the wound and the bridge for many colonised peoples

Meghan

How is this exploration manifesting in your project, Rhizome of Babel?

Kosisochukwu

I’m really excited about Rhizome of Babel as a project that allows me to take a lot of these questions and ideas and apply them in a way that takes me further out of my comfort zone, both in terms of medium and themes. I’m grateful for Mozilla—the parent company for Firefox—for reaching out to me to be part of the annual digital festival, MozFest, and giving me the opportunity and time to further flesh out my initial idea/contribution to the festival.

As it stands, Rhizome of Babel is an interactive digital project that I am creating with the help of Lucas LaRochelle, a brilliant Montreal-based multidisciplinary designer and researcher, that re-examines the biblical tale of the Tower of Babel from an anti-imperialist and ecological perspective. The project sees in the original story’s valorization of a unified language evidence of imperialist conquest and epistemicide—the destruction of indigenous knowledge systems and languages. The final product will be an interactive audio-visual environment that envisions the abundance and diversity of human languages—an ecosystem in its own right—as an alternative vision of prosperity that privileges biodiversity over monoculture, opacity over transparency, relationality over hierarchy.

Instead of a tower, what the project aspires to is a rhizomatic network that stretches and expands sideways, that embraces and respects incommensurability, that asks that we develop new ways of understanding one another. Equally exciting for me is that the project will engage with ideas around biomimicry and nature-based innovation, as a way of reconceptualizing how we conceive of and understand language.

Meghan

Does your relationship to language live differently in your roles as a Senior Policy Analyst and as an artist?

Kosisochukwu

I wasn’t sure how to respond to this question initially—not because it’s a bad one, but rather because it’s one I’ve struggled to answer for a while now. What is interesting, is that I only recently remembered a statement I gave as a witness to a conference on social innovation and social finance I attended in London, Ontario in fall 2019 that speaks to so many of the themes I am now exploring but from a slightly different perspective. More specifically, in that statement, I make allusion to the Tower of Babel and the importance of finding common language as a way of creating a more inclusive social innovation and social finance sector. Here’s a quote so you can get a sense of how close yet different my ideas then were to what I am currently exploring:

‘How many of you are familiar with the legend of the Tower of Babel? In it, humankind attempts to come together to build a tower to reach the heavens, but is unable to do so because what used to be one universal language becomes mutually incomprehensible dialects. In our context, it is not only language that has the potential to divide us, but also these silos that represent different sectors, different organisational types, and different forms of knowledge production—be it institutional knowledge production within universities or knowledge that is derived from being in community or on the land.’

In this quote, and at this time, I was romanticising the notion of a common language in a way that saw in a diversity of terms and languages a potential source of division. This is exactly the kind of rhetoric that wa Thiong’o warns against, this belief that a universal language—often that of the coloniser—is needed to unite groups that would otherwise remain divided. Though the impetus remains the same, I am guided by a desire to bring communities together. The way I approach it today is through a desire to value incommensurability and the ways in which it forces us to relate differently, to find new ways of communicating, rather than feeling the need to make one particular, more ‘universal’ language more inclusive. Here I am turning to the work of Edouard Glissant to better understand what this can look like theoretically and hoping to find ways of bringing that into practice through the installation.

...this belief that a universal language—often that of the coloniser—is needed to unite groups that would otherwise remain divided.

Image: Kosisochukwu Nnebe participating in witness ceremony at

ECONOUS, a social innovation conference, in 2019.

Meghan

Kosisochukwu

Getting out of my comfort zone. Long walks. The Ultimatum on Netflix—it’s a whole mess. My family and friends. The knowledge that I am intentionally creating this life that I’ve chosen to live.