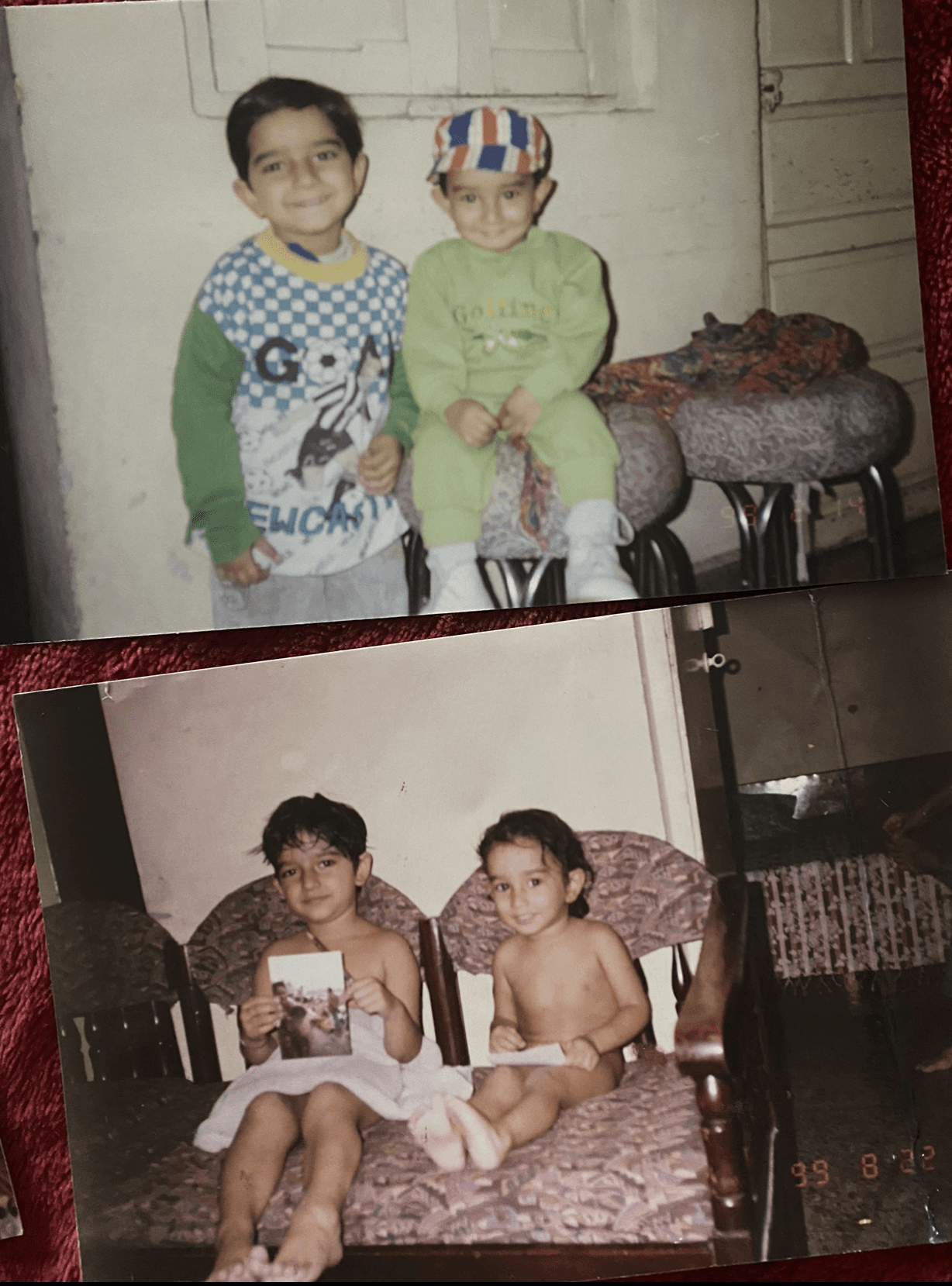

My childhood has been somewhat unconventional.

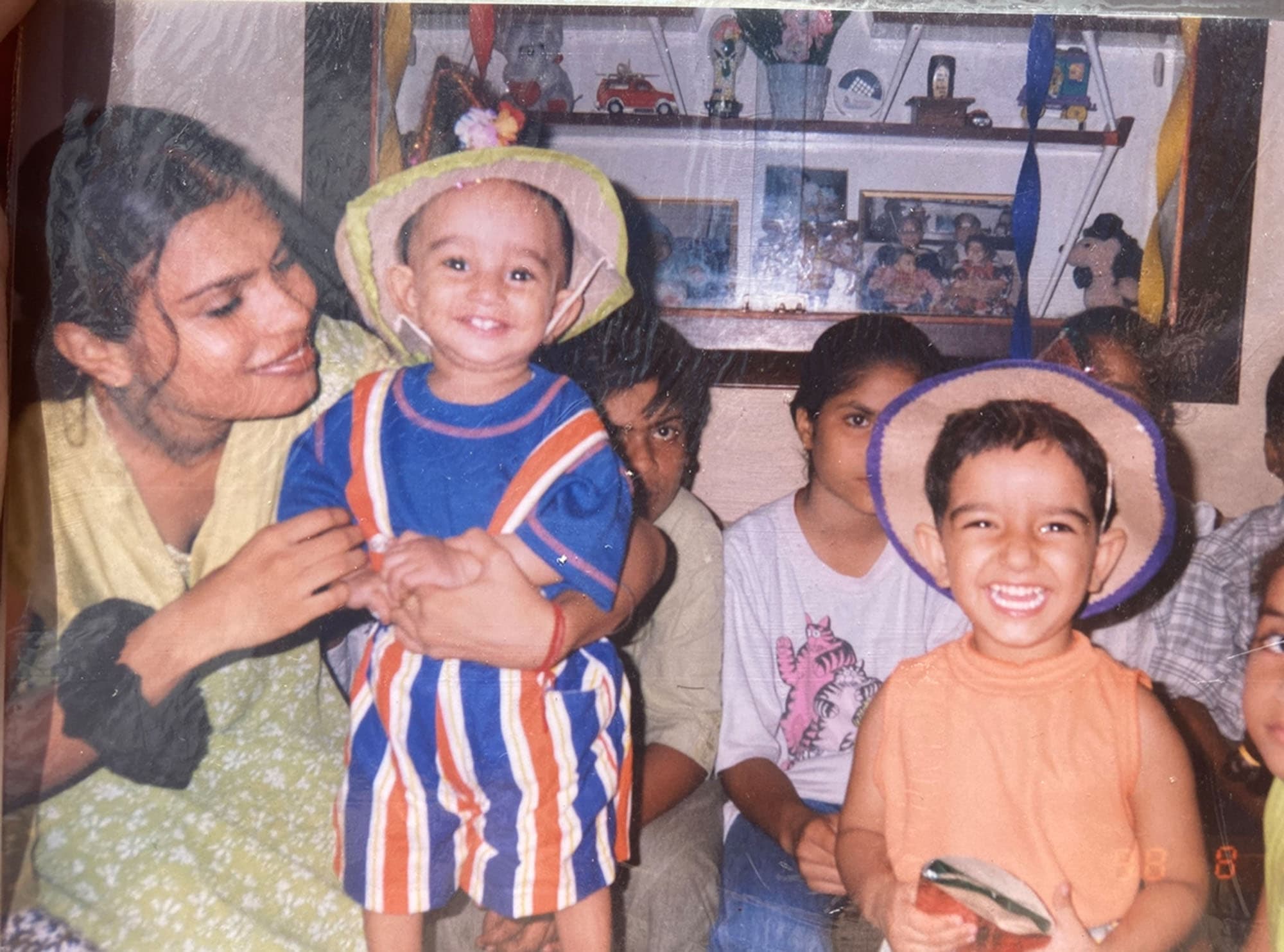

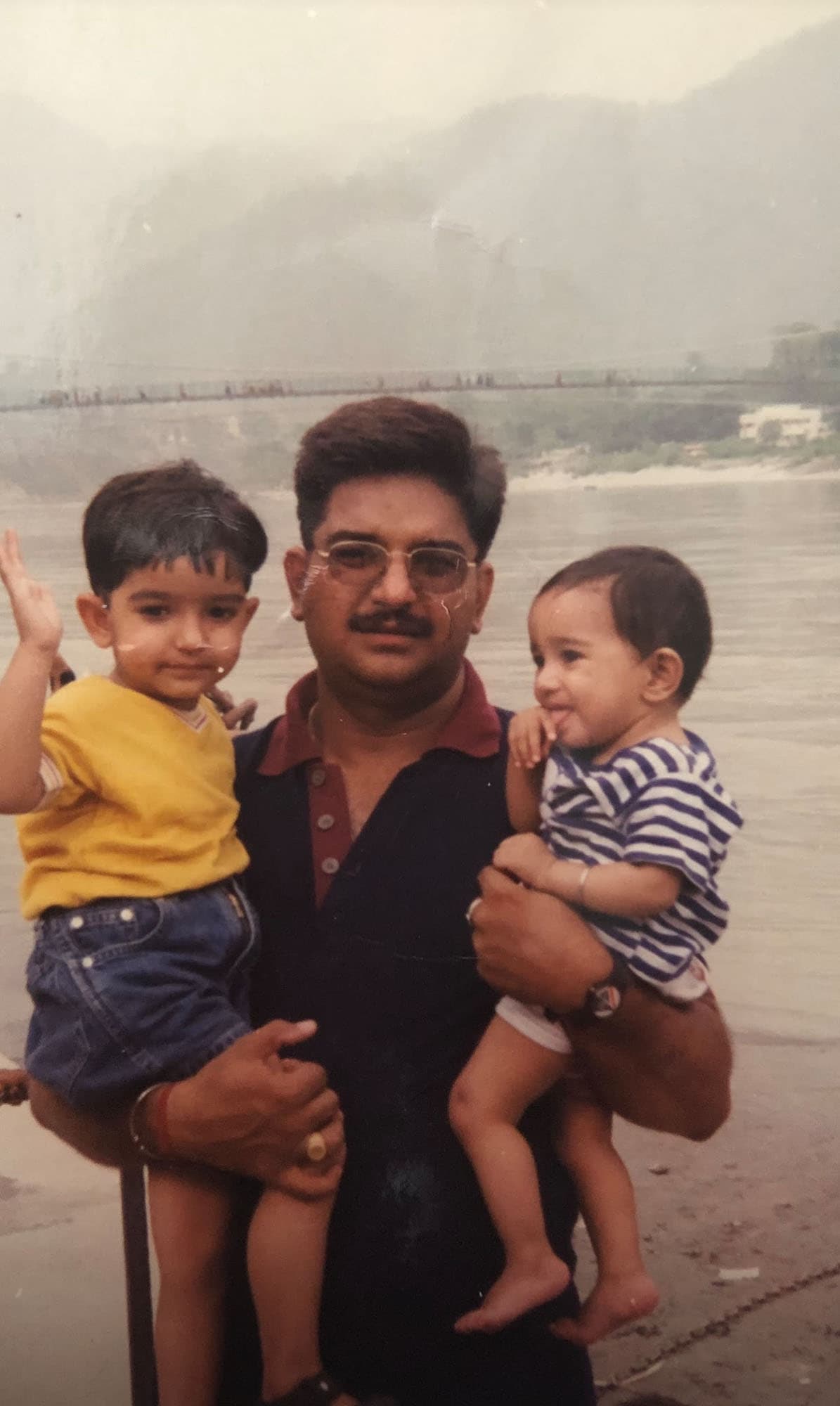

Born and raised in India, within a Hindu family, in a metropolitan city, I was the first grandchild in the family. Everyone was convinced the baby was going to be a boy. On one cold Delhi afternoon, my mom’s greatest wish came true when leaving the hospital with a baby girl in her arms, me.

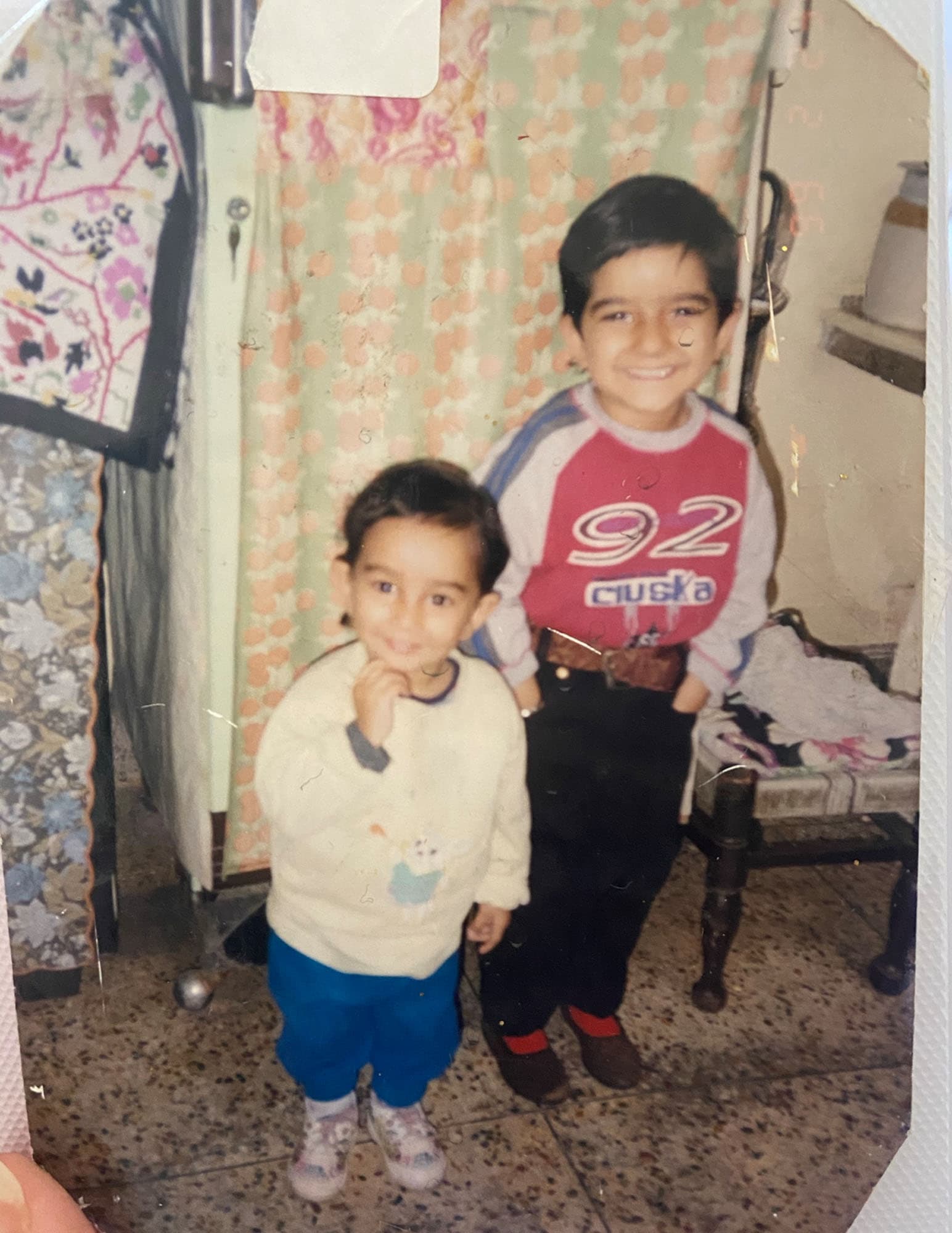

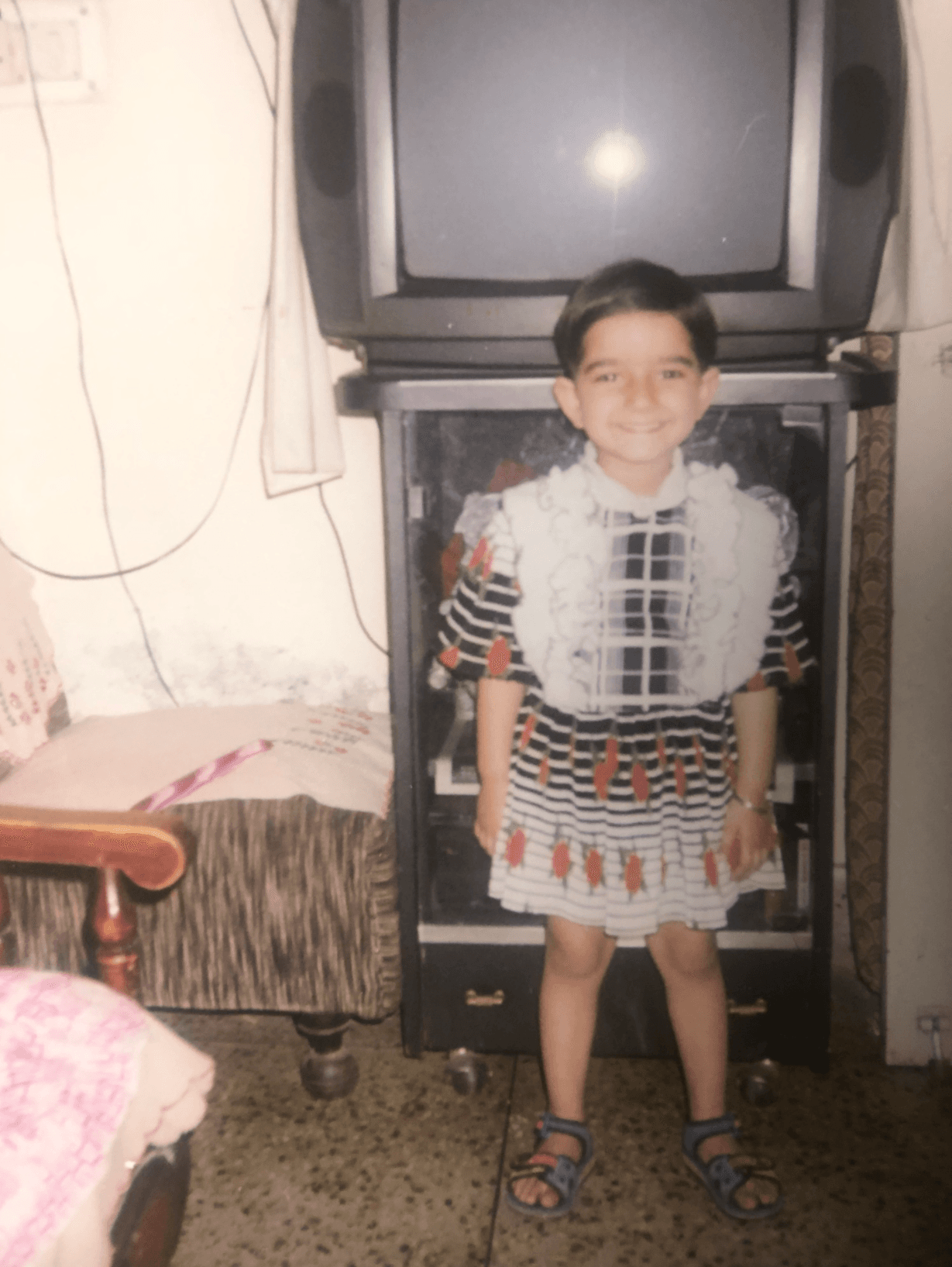

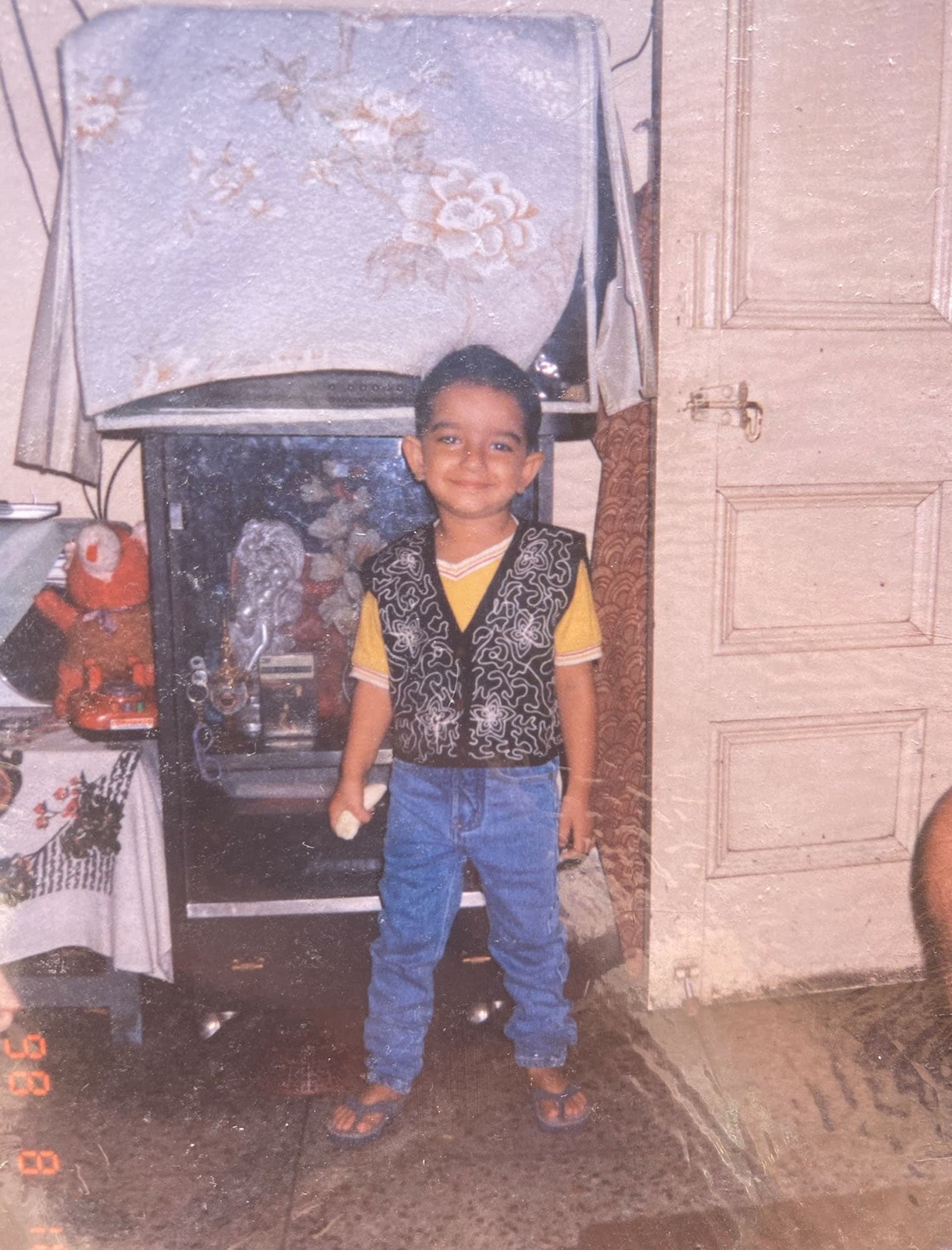

There was no explicit direction on how I should perform gender growing up. Wardrobe played a perfunctory role rather than social. I dressed up in what my parents thought was cool or when cold, what kept me warm. I went to my dad’s barber, keeping a short cut because long hair proved difficult for my parents to manage. I’d play cricket with boys while pretending to be on X-Factor with the girls.

We didn’t talk about gender or sexuality in definitive terms. No one told me gay is bad growing up. Nobody told me it was okay either. My family didn’t talk about it. The neighbours didn’t talk about it. The media didn’t talk about it. The LGBTQ+ community was unfamiliar to me.

The Khusaraa* community was the only exception. They are recognized as a third gender but our interactions were limited to just celebratory occasions. We’d bring them over to sing songs and bless us during special moments, like the birth of a child or the purchase of a new home. I didn’t get the opportunity to have conversations with them.

My curiosities-and stubbornness- led me to determine what felt right and wrong for my own self. I had crushes on school boys and also my best friends who I’d play dolls with. My first kiss was with a girl from my neighborhood who I’d play house with. I pretended to be the working husband who would come home to his loving wife.

I don’t think there is a Hindi word for people who love outside of the “norm.”

Nothing was ever forced upon me. Who I should be in public and private settings during those days was pretty fluid. This fluidity led me to explore the world the way I saw it and I drew my own conclusions from it.

This changed in my pre-tween years.

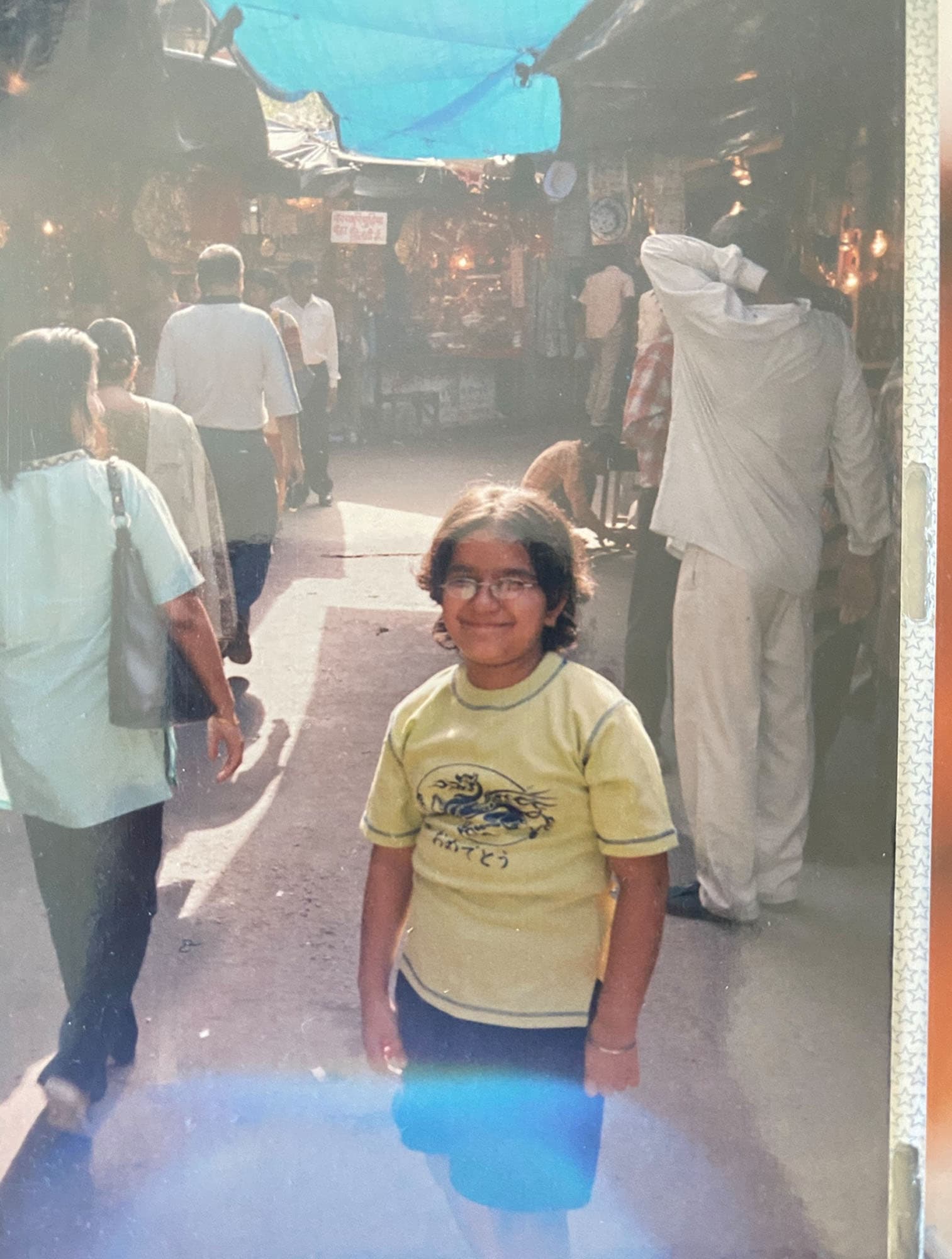

I moved to Canada at the age of 11 and gender was predominantly categorized in the binary, pink or blue. This binary felt ubiquitous, especially how girls expressed their sex through such gendered expectations. The use of makeup and fashion, norms surrounding universal beauty standards, the polarized culture shocked me. My lack of participation in assimilating to those standards were flagged by my worried parents who began coaxing me to be like “the other girls.”

I didn’t because I couldn’t understand.

Queer People have been present and existed throughout human history, especially in the pre-colonial world. However, the act of loving, and our performance of it, felt politicized in the West. It felt like gender was used as a tool to further push the narrative of othering rather than natural. I did not understand this. I couldn’t understand that an act so sweet and gentle as queer love could ever be met with cruelty.

To be honest, I still don’t understand this so this culture shock still exists for me today.

Instead of focusing on that normative ubiquity,

I sought out different kinds of people from all over the world who expressed themselves in the creative ways that best suited them. It was fascinating to see this in practice, and I believe this informed my way to move forward in my own queer journey. Even though my family and I never explicitly talked about the community, our acceptance to let others live their own life was mutually understood and respected. My parents were in awe of the drag queens who strutted down Church Street. My mom thought these 6” tall women were nothing more than glamorous models on their way to work.

As I learned more about this space, I shared that knowledge as much as I could with my parents.

I made sure this was discussed in our house even though I wasn’t fully out yet. I still recall taking my first social sciences class and learning the difference between “sex” and “gender” – the knowledge blew me away. Accepting that gender is performative, the various pieces of the puzzle began falling into place for me.

Learning the language, the acronyms, the meaning behind it all – it was a struggle to identify with something that didn’t confine me into a box. I hated labels but later understood the importance that comes from having your lived experiences expressed to others with such ease. It also helped me mould this fluid idea I had of my self identity into something I could communicate with people.

I recognize that my experience is very unique and privileged. The openness afforded to me in childhood, to be free to truly explore the idea of myself, and my stubbornness to trust in my own sense of right and wrong, has led me to be who I am today. There is loads to say about the impact of lack of representation I had growing up but when I look into my history, and how in precolonial India gender and sex and desire for whomever were considered natural, even powerful, I see myself amongst them.

*transwomen (male-to-female transsexual or transgender individuals) in India