We have a 6 month child. When the world stopped to show its sickness, we moved to the Quebec countryside, 15-minutes away from my childhood home. I am grateful for our walls, the land, the security, but at times, feel caged by the proximity to familiarity. In past lives, my constructions of self shifted relationally- talks and walks ebbing with airs of difference. The luxury of escapism. I am back to the familiar limestone faces of my past, reminded that it is easier to construct versions of self when the histories of self aren’t minutes down Highway 105. Perhaps, that is why I sing – to have the freedom to experiment with identity in a way that feels safe. Perhaps, I sing because the dichotomy of degradation and distinction is a form of flagellation. Perhaps, I sing to reclaim a body that I didn’t have comfort in for a long time. Perhaps, I sing because I have the privilege of singing and I need the money. Perhaps, I do not sing right now. I listen. I hear the circles of time in these thin walls.

While this piece documents the soundscape of my home within the span of an evening, it was written over the course of many. Differences in the tones and timbres that are perceived orally and transcribed in written word mark the shifts in cognition at various states of sleeplessness – and states of wellbeing. Writing on the sounds of my home within pandemic parental isolation was an act of feminist politics to mark the noises of ‘the domestic’ as artful. Here I acknowledge that radical reflexivity and abandon in written word is not nearly new, but new to me. The practice of writing in such a way has changed my attention to sound, listening, and ‘music’ alike.

In acknowledging the phenomenology of new motherhood as both a transformative and subjective experience, the drive to mark this space within the COVID-19 pandemic proved problematic. First, in the tensions between the acts of listening and writing on listening. In writing on sound, the internal sounds (specifically, the mental construction of sentences) often dominated –or washed out – other sounds. These internal sounds often superseded the act of listening itself, either by muddling or distracting. The repercussions of transcribing sounds and the effects of sound through written word was also troubled by recall and performativity. When I was able to write reflectively during the process of deep listening, the synesthesia of sound and word was more intuitive and poetic. This was often in moments of solitude, which were rarely found. When writing was a more conscious act, engaged in a remembering of sound, or a listening to ‘archived’ versions of sounds, I struggled to resist the impulse to construct a narrative rooted in individualism and teleological narrative. As an interpreter by trade, reflexivity is challenging, as it demands an interrogation of self and I struggle with the vanity of the process.

When listening to the sounds of my daughter, I was rarely physically able to write. The possibility that my daughter was subjected to my distraction and internal sounds engendered both a sense of guilt and reticence toward documenting her noises. Here, I consider whether archiving the domestic was perhaps more exploitative than political. Was I producing work at the cost of my family’s privacy? Was I distracted from attending to my daughter by considering her sounds? Acknowledging the theoretical and gendered tensions that exist in legitimizing the ‘public’, rather than private, through written word, I now more wholly understand the value in safeguarding, in concealing. Radical, wolven protection as a means of love and an antithesis to hungry knowledge. Perhaps the domestic goes unarchived, not because of its lesser productive value, but because gaze is not welcome here. It is in these tensions of performativity, exploitation, selflessness, privacy, deep-body femininity that are the inherent and inherited contradictions in my positionality. And yet, this process was both cathartic, formative, and stirring.

6:00 PM

The pulse of my home lives in a front neck tension between elation and dehydrated tears. My soundscape is a dishwasher and child’s breath. The drum of iron-rich well water slogs through the ventricles of my partner in domesticity, etching white, circular stains on its guests while my baby sleeps. I feel the inaudible in Motherhood. The weight of her breath in the space between midnight synaptic thoughts that foggy the possibility for clarity. A vibratory thing. A feeling, not a sound. A hummed gratitude for the empty-bellied breathlessness of watching.

The night noise of my home can be described as the ways in which electronic appliances fill the anticipatory gaps between child sounds. We are quiet here. We don’t make music, but the oven timer has a four bar tune that we conduct for the baby as a joke. The sting of the HEPA air purifier peers through our bedroom door (she still sleeps in the bed. I couldn’t lift her when they cut her out of me.) By the time the air reaches the living room, it is tuned to a C5. The initial woosh of the dishwasher marks the beginning of the cycle – it’s pulses ride upon the drone of recycled pure air in our attempt to layer sound to cancel noise. The furnace rattles unaffordably and my head tingles with overstimulation. My partner has noted my oppressive desire for quiet. It may be my whiteness or the sliver of my father’s hyperactivity that has filtered through my genes. Filtration- of sound, of air, of water- is a ubiquitous conversation in our home.

Zzzzzzshhh pa pa pa pa

I came here, shivering nights, terrified of the bones of newness. I had no fluids and I thought the water would kill you, baby. I trained my body ragged for sleeplessness with panic-eyed chaos. I knocked a hole in the wall and melted into a version of a woman whose tight hips meant that she was less than whole.

Chugging metallically against pale trickles, my friend spurts over the sound of my love’s conversation with his father. It huffs deep waves and closed throat breaths, rumbling in an effort to gift privacy. I eavesdrop and then worry about the Manganese in the water, my baby’s health, and when I will afford to buy a well filtration system. It is my privilege that allows me to filter water and sieve hardness from my daughter’s future. Pulses and focused jet streams accompany the thoughts that jolt inaudibly during the working night hours. Sentences being constructed as clearly as spoken. Projects for next life survival.

“This project aims to examine the role of the relational in cross-genre collaborative forms”…

Shhhhhhhzzzz zzzzz zzzzz zzzzz

The dated version of feminism I carry has appropriated versions of maleness that don’t hold water in these times, but I work for us and I work and I work. I know- in theory – that these constructs of productivity should be challenged, but my night mind is a survivalist vulture and the words, and new theories, and new knowledges snap fiercely. It is somewhere between anxiety, guilt, and luxury.

Can you hear chests tightening? Hips popping and ligaments restructuring? What does dehydration sound like? There is a squeaky space where my collar bone connects to my neck muscles.

ZZZZpp ZZZZpp ZZZZpp CAH

My daughter cackles and my love goes to her as I tap invasive words about their life. Writing words feels false and hungry. I hear him working her, bouncing and doing the Shhhh song that we do when she nevers sleeps. She never sleeps but I’m not going to tell you that. I know she is close, when she lets her neck go loose. She likes the feeling of speaking through the rhythm of our bounce. My tapping is making my neck sick. This is not the time to tap. My neck cracks and it is hard to hear through her magnetism.

The closed mouth ‘ng’ sounds (like the end of the word ‘sing’) calls me to the bedroom. She doesn’t open her mouth when she needs to feel closeness. The safeguarding of our sound and our open-mouthed vowels is a consequence of womanhood. I was once told that if I sing without a generosity of openness, that the noises are for myself and not for the people. Goat trill of hunger, or the need to be close.

I used to trill to be close to people, my girl, I understand.

She releases the back of her throat as she drinks. Soft ‘cuhs’ where the back of her tongue flicks her palate. Her unsoiled finger flesh tips against my chest and we sleep.

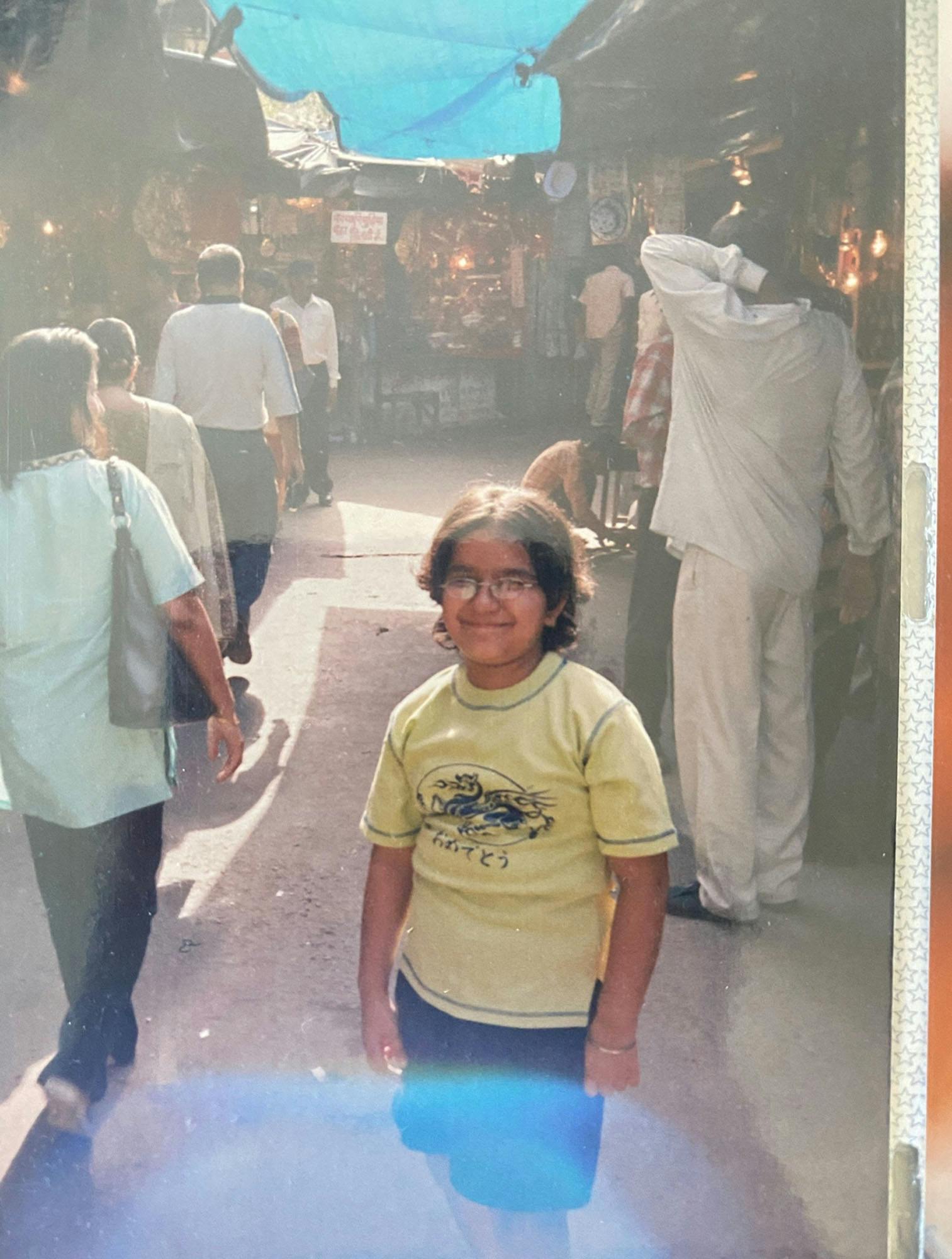

It’s been a year since the illness of the world became more visible. An old friend lost comes to me in a dream wearing a yellow tunic to mark a year. “I am an angel, she says. “I’m just checking in on your rehearsals.”

5:45 AM

In the morning, when the new sky peaks over the River Zibi – past the stolen golf course and into our little home, I hear a thud and I wonder if a bird has died and if houses and highways should exist between a forest and a river. I check on the imagined bird and listen to the sound of my gate. Heavy on the left, because my pelvis couldn’t let you come out ‘the natural way.’

Thud, tip, Thud, tip

I’ve learned to walk through my feet to help the pain and because I’m too tired to be graceful. Women are tired but we know better than to show it. My posture is weighted by the front-heavy newness of giving. I was taught to stand tall, but leaning forward to listen feels more generous.

Fast squishes of yellow, popcorn smelling digestion call me from the imagined bird. If I smile at you before the yellow sun, I won’t be able to go back to sleep.

Crisp open white diaper.

Wipe 1

Wipe 2

Wipe 3

Wipe 4

Guilty for the waste but not guilty enough to stop using them.

Drop

“We’ll give up meat instead.”

Crisp closed

My daughter crackles the sound of her finger-nail thin vocal cords awake with wide vowels. The clear ‘Ah’ kicked awake as it erupts into bubbles of spitty lip trills. She gurgles the spit from front to back, reaching her index finger into her mouth to help her tongue open her little cavity. I know from my past life that by circling her finger inside her mouth, she is creating space for phonation. I am self-congratulatory- I understand things like vocal development and soft palates and it makes me feel useful.

AGOO AAGAADAAAAA

I go to the kitchen to get a glass of water and take some vitamins. The water cooler of safety gurgles and I hear you grow.

I come back to your unsoiled fingers. When my body smells you I drip pearls of life on the hardwood floor. White liquids of your reliance. You have tempered my restlessness. I will find aquifers for you and will freshen air. I will pull disease from this earth before I let you feel harm. This is a whole body love.

We are going to Toronto to make an opera and I don’t know what to feel

The sound of metal tastes and surrenders. Of salt and futures. One year has passed

I cried the other night for the first time since you were born. When we were in my body together, I would cry into the still hours about the radon in the hills that was seeping through the basement cracks. My love’s voice is calm, telling me that he will support us when I go back to work. He will make us chicken soup and feed you at the right time. We are a being, we three. In these new walls, we are post-gender- filling the gaps and spaces of support and need with an osmosis of empathy. Everything has changed.

We installed a radon pump. It hums. My tears release my jaw and I can hear the space between my teeth unstick.