Editor's Note

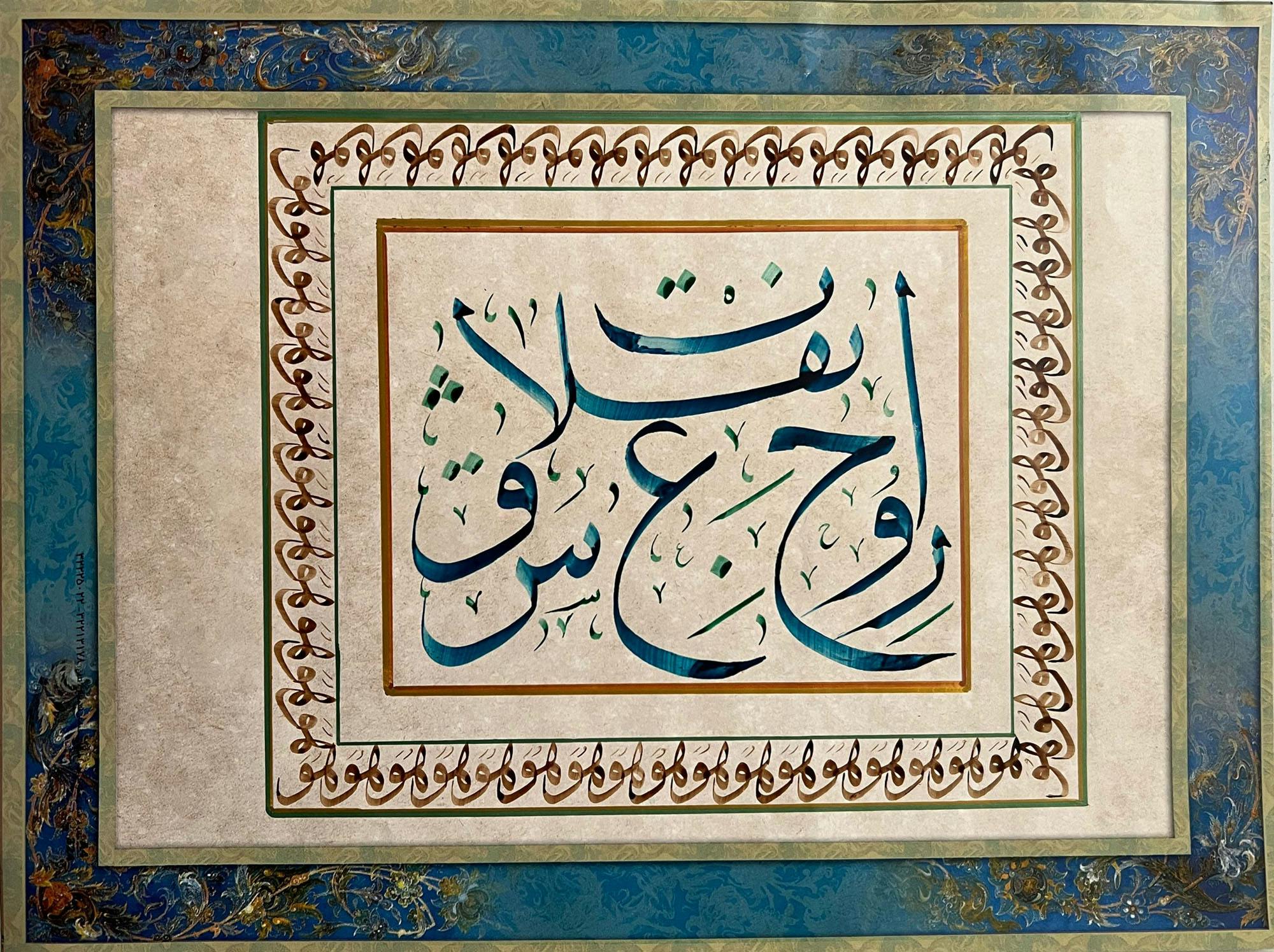

One of my earliest core memories has been fighting for and longing to live in a world without gender, caste, and societal hierarchies. My father and I debate on such matters, him advocating for Punjabi tradition that upheld such hierarchies and me advocating for Sikh tradition which abolished them. This dissonance has strained our relationship ever since I was a little girl. Witnessing the differential treatment between my brother, my sisters and I led me to question patriarchal traditions ever since.

He would take me to Dukhia uncle’s house as a disciplinary event, hoping the town’s Sikh academic elder would impart some perspective to change my way of being. My way of being that was on trial included playing soccer with boys on the playground in kindergarten or questioning why my brother wasn’t held to the same household duties as my sisters. My brother had disproportionate emotional affection, individual freedom, labour exemptions, and even, financial access. In fact, even cultural festivals and practices favoured him, Lohri to Rakhri, celebrating his gender over mine. At the age of five, I staged a coup and told my mother I would stab myself if a rakhri wasn’t tied on me too. The scene was successful in a Bollywood film (India’s most influential cultural driver) yet I was thoroughly ridiculed. The truth is, my conviction about gender was earnest and true and not satirical. I was exasperated by the dissonance between my cultural and religious practice as I couldn’t understand gender difference. I was too young to articulate this fluid world I longed to live in- one that felt more aligned with my own Sikh beliefs than the socio-cultural segregational orders of society which I’ll elaborate more on later. When Dukhia uncle asked me why I’m misbehaving, I asked him to explain how gender differences can exist in Sikhi and that if he can help me understand, I would stop my inquiries. He looked at my father and said, she’s not wrong. It’s a shame that I was delighted in this acceptance- that an elder male had to validate my values.

Nothing changed. On the drive to Mission Hill Elementary each morning, my mom would recite directives to her daughters. There were three of us but as the youngest, and in accordance with universal notions of beauty, popularity, rebellion, her messages were mainly directed to me as I posed the greatest risk assimilating to Western modernity. Most of my friends were white and as a fair skinned and skinnier girl, my parents were burdened with ensuring I remain chaste and not corrupt like other girls in town. “The girl child carries the burden of the household name and reputation. Our family honour, the honour of your ancestor’s turban, rests upon your shoulders as girls. It took our ancestors and us a lifetime to earn this from society and yet it can be taken away within minutes by you,” she would explain.

“Neemi rakh ke turnah,” she would demand. This means look down as you walk.

We were never to receive or respond to the gaze of others, especially that of the male gaze. Any act of defiance towards this would be inspected and surveilled by the community of South Asian immigrants. They mostly lived on Mission Hill, the region in Vernon where the Sikh Gurudwara was situated, and as a result, most South Asian immigrants as well. School was a mere five minute drive from our home in the lower income neighbourhood of Vernon, B.C.

Seeso aunty, Jaswinder aunty, the Mission Hill diaspora culturally reified the messages of our socio-cultural upbringing- oscillating in its contradiction of what the ethos of the egalitarian religion is versus the patriarchal cultural practice. We would pass the Gurudwara en route to school and bow our heads in Its direction. Such a Presence would devoutly contend the Punjabi experience of subordination and for me, the teachings of the faith held more influence. Despite such a resolution, my material circumstances weighed on me stronger than my spiritual conviction. Suppose growing up in a sociocultural and religious panopticon had significant consequences to my consciousness. I often wonder if the seeds of agoraphobia were planted in me then.

My parents imparted the teachings of Sikhism with so much care to my siblings and I at a young age as well. It was their way of preserving their own sense of identity and belonging while being away from their homeland or perhaps an investment towards ensuring these teachings carry forward into an unknown future on new lands. Both reasons are understandable to the migratory experience and for me, prove to be fundamental to my core being. The faith instilled notions of seva, equality, self determination and social justice in me which I practice to this day. My spirit never delineated from these ethical codes because any other way of being did not make sense to me. This caused tense divisiveness and conflict between myself and others in both the Punjabi home I resided in and the Western world outside.

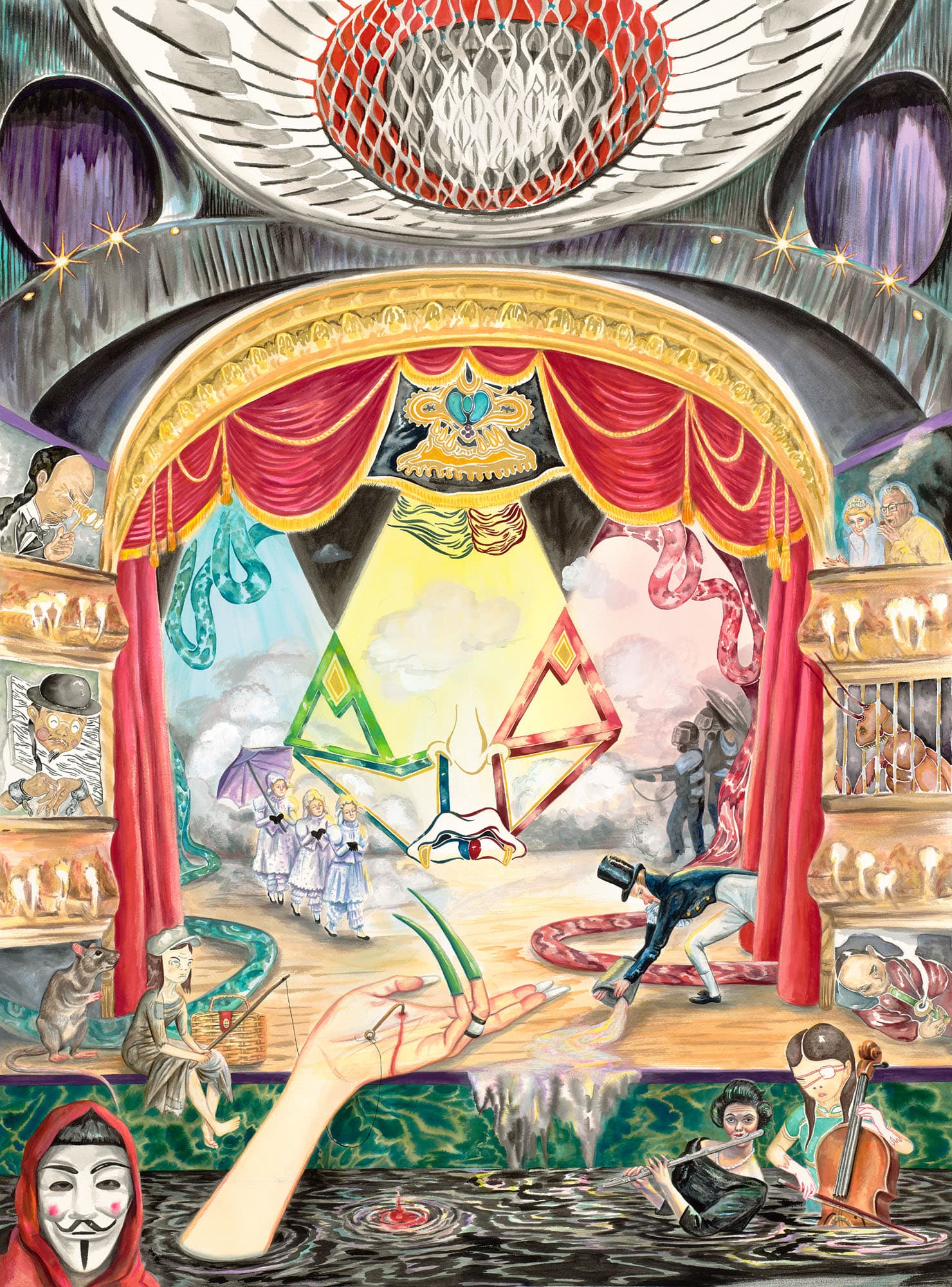

The togetherness I sought was found in the imaginary. A new world created from a place of healing rather than trauma. Futures that resist patriarchal colonialisms. Futures that, based on ancestral knowledge, build ecologies of truth serving all visible and invisible beings in a collective consciousness. This world transcends race, caste, class, sex, borders and barriers. This world was inspired by the matriarchal divine– one that practices love above all- even if the current world continues to extract from such an abundant practice. My perpetual atavistic curiosities coupled with pessimistic futurism currently inspire how I look to build a conceptual new world. Our territorial lineages have created hierarchies costing us the health of both matriarchal divines: Mother Nature and Earth Mother.

Feminism spoke to me as much as abolition. I began to vehemently centre radical love, eroticism, and joy as a manifesto to resist the deterioration of our current yuga.In doing so, I had the privilege to build a relationship with Debi Wong, founding artistic director of re:Naissance Opera. We connected over our shared thoughts on abolishing old systems of hierarchy and societal organization and approaching new world design from a space of joy rather than trauma. Our conversations coincided with Black feminist scholars I was reading at the time and the exploration of what it means to be a Sikh feminist abolitionist. My understanding of what Audre Lorde writes is that old systems of design cannot be dismantled by the master’s tools. It can spark a temporary change but not sustain the necessary changes of good that are required. Non-profit structures and governance models have been failing IBPOC-led organizations for a long time and consequently, IBPOC audiences as well. The events of the past three years during the pandemic have exposed the white supremacist and patriarchal biases in the systems and structures we worked within and organizational change has often been framed by corporate vocabulary and values.

We quickly realized that we’d need to assemble a team of IPBOC thought leaders from all aspects of societal design to think about new world design with us. This formed the Imaginarium, a year-long arts-based cross-sectoral world-building initiative to find solutions for governance and organizational structures. We built a team of IBPOC artists, storytellers, mental health workers, climate change scientists, leaders in the tech sector, and Indigenous knowledge keepers. This team of dreamers, as we called them, engaged in science-fiction inspired world-building workshops to imagine a society that embodies our shared core values and enshrines IBPOC worldviews marginalized by mainstream culture. Debi and I met weekly for eight months where we spoke about our prayers for the future, our ideas on approach, and hope for possible outputs. Willendorf (my matriarchal research collective) collected this feedback and designed the approach and felt experience in order to achieve what we intended to: safeguard the spirits of the participants so they can dream of better futures. We wanted the dreamers to feel safe, healed, joy, playfulness, and intelligence and to leave feeling a sense of renewed hope and community that surrounded them even once the physical experience was over. We thought about all aspects of the experience and emotion that we hoped to create for the participants of the Imaginarium and began to think about who to invite: Micheal Running Wolf, Howie Tsui, Renae Morriseau, Stephanie Wong, Teiya Kasahara, Debi Wong, Will Selvis Trevor Twells, Tarun Nayer, Kunal Lodhia, Dr. Andrea Fatona, and Rinaldo Walcott.

We flew those with available schedules to Vancouver, British Columbia to participate in person. They were paid above the suggested daily fees that CARFAC proposes. We lodged and fed everyone in a mansion surrounded by the old trees of Shaughnessy. The space had enough rooms for everybody and many spaces that encourage group participation. We meditated together to inspire connectivity. We foraged natural materials from the backyard and built physical worlds out of the materials collected. This inspired childlike wonder and a reflexive, joy-based creation. We didn’t invite anybody to document or photograph the Imaginarium. We didn’t want any external factors to shift our collective energy, observe our activities, and/or attempt to synthesize our ideas. We took care of our dreamers so they could take care of our Imaginarium in what I’ve always called circular economies of love.

Each step of the process was thoughtfully designed in my mind at a pace that felt true in my body. In an effort to resist western design modalities, I researched ancient ways of knowledge building and sharing, asking scholars studying Sikh theology, reading essays from Black feminists, engrossing myself in the lectures of Sarah Sharma, Director of Institute of Communication, Culture, Information, and Technology. The more I invested in my higher learning, the more I felt my body heal, the more I allowed myself to think about my earliest core memories. I reframed my experience as an unwanted girl child by forgiving my mother and trying to accept my father as he is. It became apparent to me that they too suffered from the same patriarchal systems of oppression in India as their foreparents did before them. I actively thought about the people in my life that broke my heart and trust as I underwent such a shedding and sent prayers towards them. Ultimately, I found myself summoning my ancestors to help inform my thoughts, validate my decisions, and guide my actions. Individual transformation was the first step towards realizing the dream of a world I wanted to raise our daughters in. That was and will continue to be the center point of Imaginarium, for me.