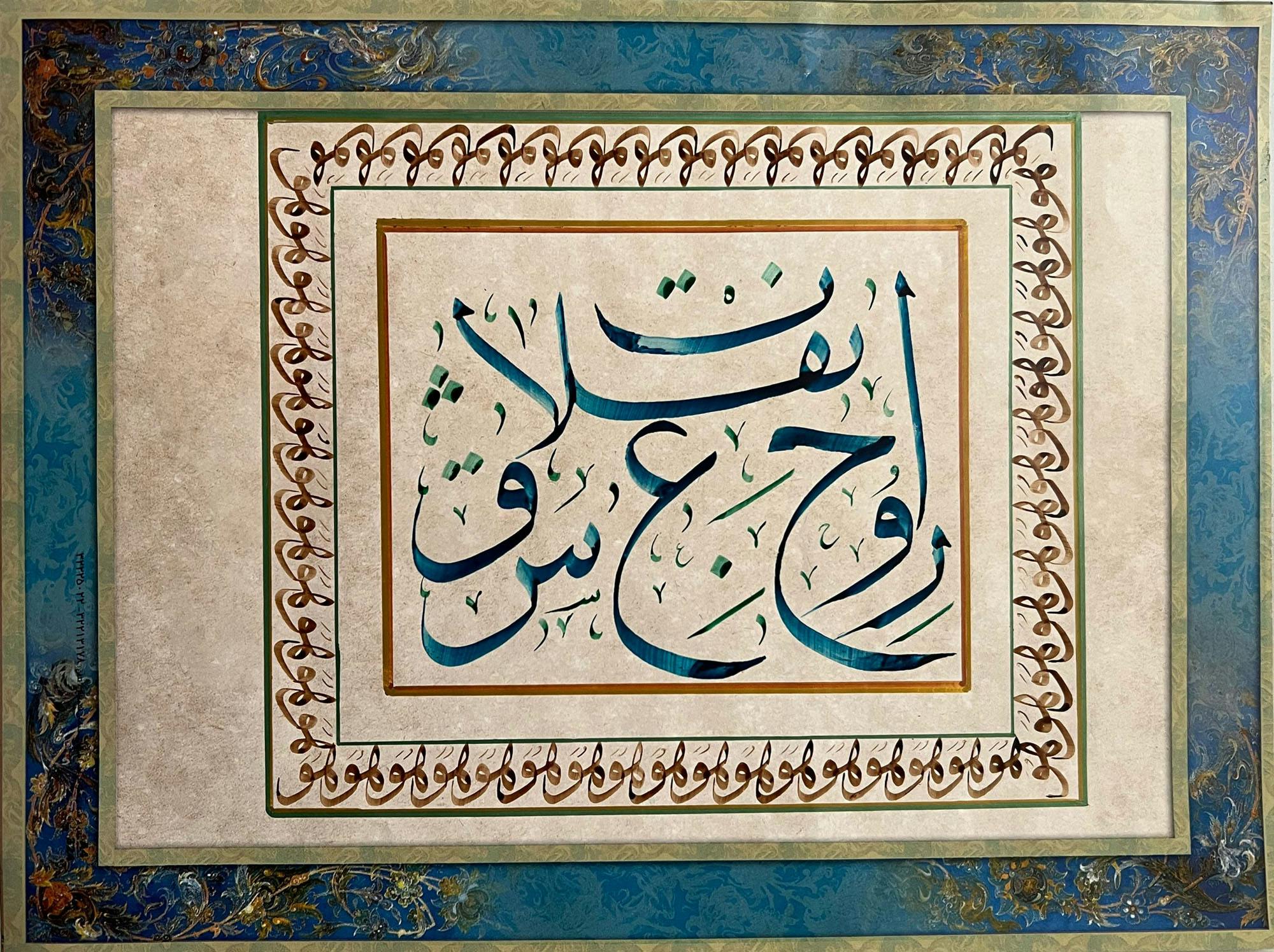

Rooh, Ishq and Inquilab : Towards an Understanding of Ecumenical Mysticism

Calligraphic writing as a tangible connection with our divine and its role in transcending temporal and structural boundaries.

tire ishq kī intihā chāhtā huuñ, mirī sādgī dekh kyā chāhtā huuñ

ye jannat mubārak rahe zāhidoñ ko, ki maiñ aap kā sāmnā chāhtā huuñ -Allama Iqbal

[ All I desire is the ultimate love of God, that is how simple my desires are. The heavens are for the religiously devout, I only desire to be able to see you (understood as oneness with the divine)]

Calligraphy as an art form for me is a manifestation of tangible oneness with the higher spirit that not only transcends the boundaries of structured religion but also temporalities. It is an inward looking communication with oneself (inner self), the medium (visual art) and the higher spirit (God) to overcome the disadvantages of verbal language and boundaries of representation (especially in Islam and Sikhism). Islamic theology believes that the pen is one of Allah’s first creations. Sufi philosophers saw this as the first intellect where the mind, body, and soul connect in mystical entanglements through writing. The centrality of script and calligraphy becomes an important experience for the soul’s emersion into the divine, for ishq and sukoon (peace within body and mind) through khatt (writing) and dhikr (Sufi practice of repeating the name of the beloved).

The coming together of Rooh, Ishq and Inquilab enmeshes the spiritual and political towards a radical understanding of love. ‘Alif’(the alphabet) and ‘Hu’(a term used in Sufi dhikr) have a powerful mystical energy for the calligrapher, similar to the chanting and writing of Ek Onkar for the Sikhs, both are connected to spiritual cognition. The Arabic script and the concept of the primordial pen are central to the connection with Allah and Islamic visual culture; a person’s life is under the shadow of his deeds being documented by the divine pen.

The spiritual connection between the pen, ink and paper are mentioned in the writings of Guru Nanak Dev Ji, who said :

“Burn emotional attachment, and grind it into ink. Transform your intelligence into the purest of paper” (Ang-16).

The impression of ink on the paper, was an experience of coming together with the beloved for Sufi Qadi Qadan,

As paper and writing on it have no distance between them, So are my beloved and myself.

And Jalaluddin Rumi believed :

My heart is like the pen in your handFrom you comes my joys and my despairs

The role of the ink and the pen in these mystical writings express the desire for oneness with God as an intimate act of submerging. Sufis were the earliest Islamic calligraphers. They used the practice as a way to visualize their beloved, and experience a kind of physical intimacy with the divine through repetitive writing and chanting. These early Sufis were also teachers and guides, transmitting knowledge through interiorizing the mystical names of God as jalal (majestic) and jamal (beautiful). This act of writing the names of God was a meditative invocation, where the souls of the Sufis connected with their divine, and desired annihilation through love- a complete submersion of the body and soul in the love of their beloved transcending temporalities.

The act of writing rhythmically created a sense of peace, patience, and focus on the divine. Personally, the experience of listening to Asma-Ul-Husna or looking at the 99 names of Allah, evokes a sensation of closeness with God. It is, for me, the closest possible experience of seeing the physical attributes of the rabb (God). Growing up in a Shia Sunni family, and seeing Allah, Muhammad, and Ali, written in beautiful Nashtaliq calligraphy, I internalized them as sacred objects and icons. The calligraphy becomes a sacred object in its own right, that is venerated, where the tangible and emotive come together to embody the soul’s connection with the divine in a visual space.

Sufis visualized the beloved (God), through the physical act of joining the huruf-e-tahajji (alphabets) as an expression of intimacy, like Hu ‘هو’. Such intertwined alphabets represent the physical intimacy that Sufi desired, to the extent of becoming one with God as God, Anal Haq (انا الحق meaning I am God).