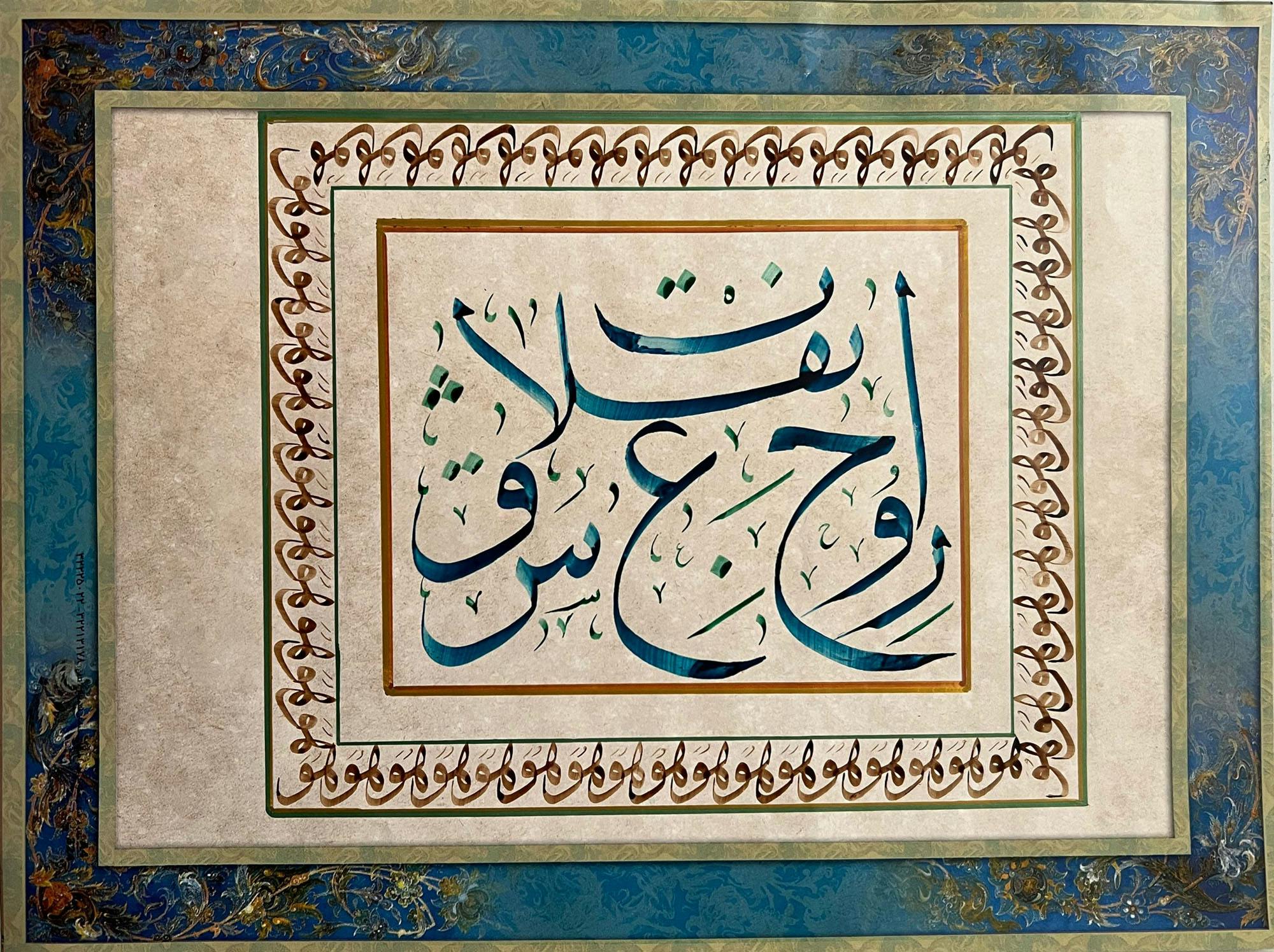

Portrait of Bao, Creative Biologist

Model: Xiyao (Miranda) Shou

In a not so distant future, a not so simple reality persists – ten billion people are poised to want the same thing that perhaps we all want.

More.

More housing and healthcare, greater access to education and more robust energy systems. And because we have been told we deserve more and newer and better, ten billion people will try to squeeze their bit of abundance from a planet already parched and gasping for air.

But perhaps there is another way?

In this era of increasing turbulence – think climate change, the encroachment of fascism, and the perpetual imminence of war – we need something to hold on to. While the tension between scarcity and abundance (the threat of too little and too much ) may present a great challenge, amidst this landscape, artists and artisans, designers and makers have perhaps one of the greatest opportunities to guide us as mediators of our future environments, to provide some semblance of a path forward.

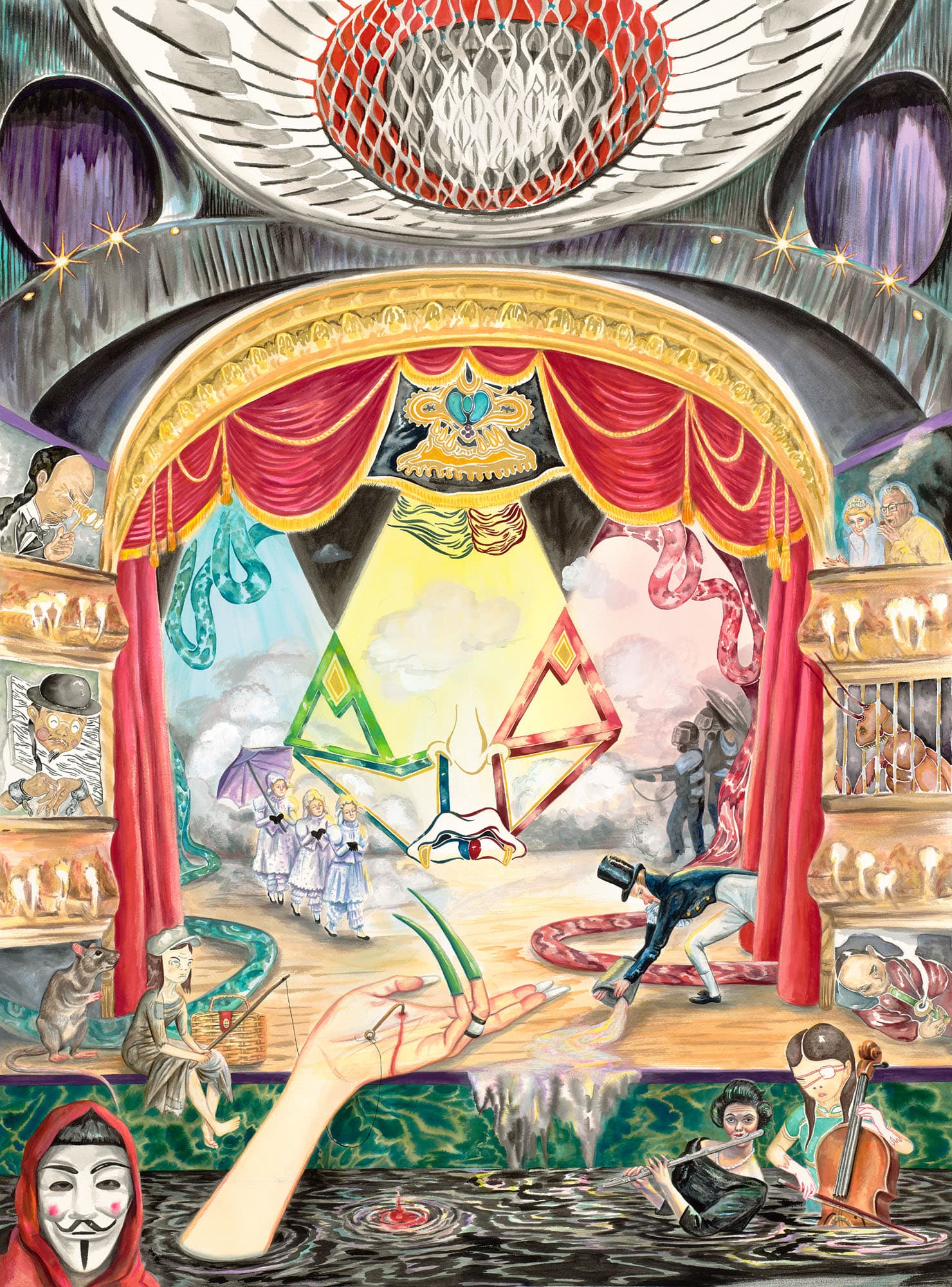

Enter Memory Work and the Mothers of Invention (MOI). Initiated by From Later studio with artist Rajni Perera and the Memory Work Collective, this speculative work imagines a world characterized by collective care and politics that value nurturing over growth.

“Hello love. Take a moment to settle and in your own time, close your eyes. We’re going to visit a future. I’m going to guide you. You can let go of whatever is on your mind for now. It’ll all be waiting for you when we return.” The narrator’s voice guides me through the sonic landscape of a future Toronto. It is smooth and mellow, bright and in moments almost ethereal. From the space between my headphones, I find myself thinking – sure, I’ll go wherever you take me.

This world is luscious without being excessive. In response to mass global disruption due to climate change, the City of Toronto has become a haven city for climate refugees. From the rich narratives and visuals to the cultural artifacts like ‘Ancestral Intelligence’ (an alternative iteration to Artificial Intelligence) and ‘cosmetic healing,’ to the aprons worn by members of the MOI, designed by Tala Kamea and Naomi Skwarna. This world has been formed slowly and intentionally. In conversation with Macy Siu and Robert Bolton, the research process itself is reminiscent of a collection of rituals in co-creation, in community. Each member of the Memory Work collective building on the offerings of their collaborators with a palpable deference towards their counterparts.

The world of Memory Work asks a lot of the listener and viewer, but it doesn’t belong to us, and may not even be for us. And yet, we find ourselves here, meditating on a collection of alternate realities and future presents.

Memory Work by Memory Work Collective

Embellished photography: Rajni Perera with Omi Thompson;

Costume design: Tala Kamea and Naomi Skwarna;

Concept: From Later

Photographed by: Samuel Engelking

This is not an exercise in predicting what will be, but a protopian provocation of what could be. We are invited to consider: What kind of collective future emerges through the incarnation of lots of new things? There are new terrains to explore, innovate within, and learn from in the world cultivated by Memory Work. New spaces of interaction, new entities to collaborate with, new design and production languages to unearth, new infrastructures, new histories, new technologies. We see these brought to life in some of the notable members of the Mothers of Invention. A loosely knit movement of political, business, and spiritual leaders, the MOI seize control of the world’s institutions, ushering a transition to new means of equitable exchange and the adoption of cooperative models in the face of lackluster resolutions to climate change in the early parts of the 21st century. Bao is a creative biologist, working with materials made from living things. Timesha, a cosmetic healer from a long line of healers, whose practice tends to physical, cosmetic, and spiritual well-being. River is a transitionist. Dom reinterprets ways of working with the land, showing us how to coax natural infrastructures and bend our human-made systems to the ways of nature. Ego is a leader, a synthesizer, she bears the moniker of the loving matriarch of the Mothers of Invention. Sam a serial surrogate, just 17 when she livecasts her first embryo transfer ritual, she’s become an influencer of sorts.

What Memory Work is bringing forward feels radical. At first glance this new world may induce apparitions of utopia. I promise you, it’s not. As N.K. Jemisin reflects in a recent interview on world-building “The catch is that revolutions hurt people. Revolutions — the most vulnerable people who are already struggling now will fall off a cliff when such a time actually happens. So revolution isn’t always a good thing. But it means something […] that people are in much larger numbers imagining better worlds or just different worlds.”

The point here is not to build a world that is pristine. The aim is to make a possible future more tangible so that we might choose which parts we’d like to adapt towards or mitigate against, what we might rework or completely leave behind. To transport the audience into a space of agency and perhaps even accountability, to hopefully reframe the notion that we must simply resign to the future happening to us. There is of course a deep privilege that comes with even being able to consider multiple paths forward, but that’s the beautiful thing about Memory Work, anyone can find their way to it in some manner or another. This world hasn’t been cocooned in some corporate tower, behind closed doors. It is of the community, in community.

Portrait of Ego, Organizer, Model: Zanette Singh

Portrait of Dom, Rewilder, Model: Cheyenne Sundance

Portrait of Sam, Serial Surrogate; Entrepreneur, Model: Mecha Clarke

Portrait of River, Transitionist, Model: Dori Tunstall

Portrait of Bao, Creative Biologist, Model: Xiyao (Miranda) Shou

Portrait of Timesha, Cosmetic Healer, Model: Jennifer Maramba

If you have the chance to make it out to The Bentway, you can visit the mural located at 250 Fort York Boulevard, Toronto, Ontario, at street level, on the east side of Strachan Avenue, under the Gardiner Expressway. A “monument to Toronto’s potential,” it offers yet another portal into the speculative future world ushered in by the Memory Work collective. And if you have some time, call 1-855-910-2050 while you’re there (or even if you aren’t), to be taken through an audio immersion of each of the six Mothers of Invention.

Because our cities and systems are inherited, I believe we have an obligation to those who come after to build better. To be designers and makers who engage in small and large acts of future-making that are locally responsive and globally engaged. Perhaps then some semblance of a path forward manifests in that space between our uncertainties today and our opportunities for tomorrow where we ask “what do I hope to leave behind and for

whom?”