The Non-Linearities of Queerness

The Non-Linearity of Queerness | An exploration of life that takes place at life's time: a boisterous "teenagehood" that emerges mid-age, a contemplative elderhood that emerges at the age of five—what if our life cycles took on a freeform?

The Non-Linearity of Queerness | An exploration of life that takes place at life’s time: a boisterous “teenagehood” that emerges mid-age, a contemplative elderhood that emerges at the age of five—what if our life cycles took on a freeform? What intergenerational communities may emerge from the pull of our own becoming?

Gathering from examples of queerness as an embodied way of being (as opposed to the confines of mere identity), this exercise in imagining shows how we all benefit from fluid, free-flowing futures and how queer folks create these fissures of freedom in our day-to-day existence: in our readiness to face familial trauma, in the creation of our own communities, and in wondrous, new textures of self.

Of one antidote to the white supremacist culture of urgency—that which falsely imposes a rushed disconnect from the body in order to reinforce power imbalance—Kenneth Jones and Tema Okun prescribes coming back to breath, and in turn, back to our embodied selves.

In this queer body, blooming with teenagehood angst and seasoned with the timeless wisdom of my kejawen Elders, I witness the colonial hauntings of such urgency and notice the ways it possess time markers whose linearity evades me: of welcoming children, building partnership, harvesting success, and, perhaps, even finding the privilege of stillness one can call home. In response, this queer sense of self practises a cyclical ritual: inhaling the expectations of compulsory heterosexuality, exhaling an expanded sense of wonder that asks, “If I am off the colonial trajectory, where, then, am I headed, and on whose timeline?”

My work with grief often reaffirms this non-linearity, engaging with the idea that we are simultaneously in the past, future and present, at all times. It is merely our focus that shifts from these tenses—not because we will it, but rather, because we are expected to do so while living with the conceptions of colonial time. Triggered by a secret scent, an unmistakable sign, a shared song; those of us who time travel through grief’s portals know the distinct ringtone of this calling and its abruptness. Those of us are born into grief—in my case, brown skinned, origami-ed tongues by languages unlearned, child of a father orphaned by motherlandlessness—we inherit this space time mobility before we have language to call it by.

Much of my work with grief is interconnected with time and how capitalism forces us to move unidirectionally in it. I find myself summoned by community members who are ready to “do something” about the pace of their bereavement, eager to process and desperate to move on. As we name this urgency and the systems (and voices) attached to it, what emerges is the revelation that our grief merely flows from a source that is arrhythmic in ways that are not unlike love. It is the interruption of that grief—our shame, the impossible pressures to go back to the way things were, an exhaustion from institutions that want to schedule that grief neatly outside of the work day—that creates resistance and causes immense pain. The work is in protecting our time from the insistence of so-called healing, and surrendering to the way grief actively shapes our personal topography in life.

Queer non-linearity is an embodied grief that allows for an exploration of life that takes place at life’s time. Freed from the exigencies of fertility timelines, we find ourselves with free-form fluidity: a first kiss in our late 20’s, a sexual awakening in our 50’s following a divorce, children in our early 40’s. We become drawn to one another by affinity rather than age, lean onto one another in ways that blurr romance, create our own blueprint to gender and find euphoria in complex answers that make a playground of the binary.

Isabella Fischer

I have written about reclaiming cultural relations with time. In Portals: Decolonizing Futures Through Time Travel and The Javanese Calendar, I was pulled by how language shapes our worldview of time, investigating how my own ontology is informed by the tenseless conjugation of the Indonesian language and the way my Javanese ancestors look to nature for its calendrical time-keeping. What is emergent in my conversations with colonial time is its fictionality of “loss.” Despite the imposition of a Gregorian calendar and 8-hour work day—or what Robbie Dick of the Cree Community of Whapmagoostui calls artificial suns— the body is time kept by something timeless that contests the past as something that slips away from us. As cultural people, we know this. I meet my ancestors again and again through an inward migration that simultaneously connects me to times that have “passed” and have yet to happen. I follow an algorithm of ritual that instantly connects me to a wealth of kejawen knowledge unaffected by the passing of time.

Queer non-linearity, is similarly spiritual work: we meet ourselves again and again as who we are, who we have been and who we’re going to be, against the memories of our loved ones and the system’s desire of our role in it. Ultimately, we follow a ceremonious call back to ourselves. Kai Cheng Thom’s Only Queer & Trans People Can Be Witches, describes “following the call” as a kind of closed magic. She writes:

our people have always followed the call

of wanting & willfulness, the flowering of forbidden knowledge

in the garden of our blasphemous bodies.

in the fecund soil of our secret hearts. we had no choice

but to answer the call. we were initiates

in a sacred order. summoned by a power

a purpose greater than ourselves, blessed

by the sacraments of blood and transmutation

we made ourselves new bodies

out of magic & moonlight. whole worlds

we built from desire & despair

we traveled time, shifted shapes

gave birth to legions of exquisite beasts

we spun the shame you gave us into gold

The term delayed adolescence, which describes queer and trans folks’s sexual awakening as a “late” coming-of-age, centers a compulsory heterosexual timeline by defining our queer blooms as off-sync. But queer non-linearity is a way of being that is exactly on time—our own time, with the body as a timekeeper.

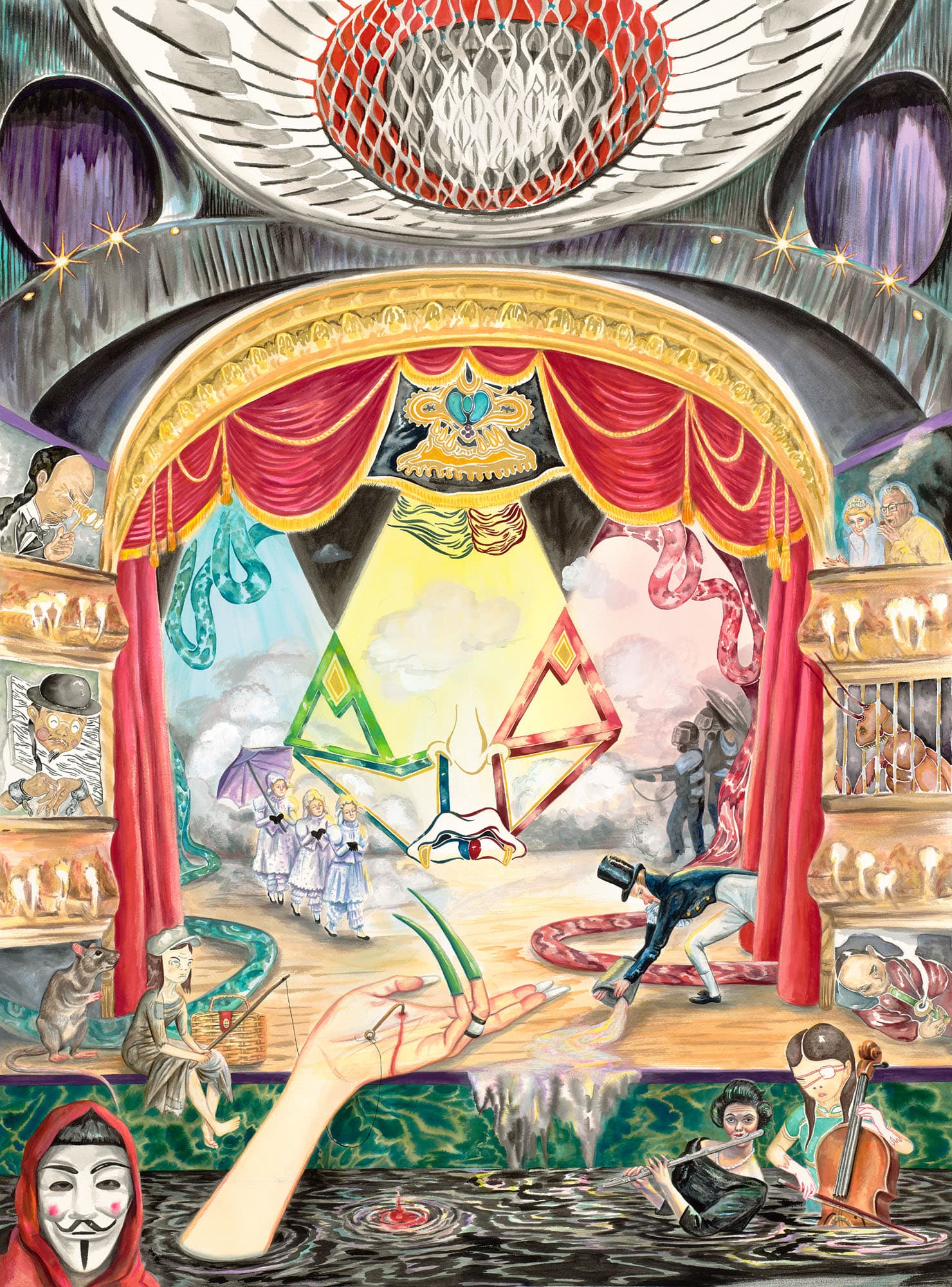

In my work, I am often asked what the opposite of grief is. And I believe that if grief is the long exhale in which we lose breath, that the inhale that precedes it is an epiphany. Queer non-linearity can be described as this eupnea through our metamorphosis—a process of becoming where we make ourselves new bodies, summon the power of our greater purposes. This epiphanized grief not only maps who we are and our roles in our communities, but also our positionalities in the ever-rapidly-changing terrain of the end-of-times including the colonial consequences of climate catastrophe. It involves simultaneously reaching into the past to inherit queer wealth from a quiet lineage of never-married or forever widowed ancestors, while also forcing us to be perpetually inventive because the erasure of our existence makes the blueprints a little more difficult to find—but we find them nonetheless.

But let me talk of the queer non-linearities I know now, and the queer future ancestors who are addressed at this present tense dwelling:

At the furthest end of East Vancouver—where a step off any east-facing sidewalk would have you suddenly in a neighbouring suburb—is the cosmique nook. It existed, first, as a spell between three friends, then manifested as a queer/trans enby home, with a backyard big enough for one border collie, a kitchen balcony suitable for one perspicaciously communicative black cat and a covid-safe open door policy for all our amourous anarchy. Where we have affinities in our desires to create a space of queer euphoria, in every other aspect we differ greatly.

Between three 30 year olds: a curly-mullet bachelor student with a sacrosanct drip coffee ritual and endless cravings for freshly baked croissants; auncle to two nibblings and graphic designer turned UX developer with a regimented need for long kitchen dates (solo or with their favourite seasonal beau); and a writer, serving 75 hours of community service for civil disobedience, with a capricious mood ripe for revolution and a collection of retro tech. At our age, our parents had children, but as a looming baby fever grows, only of us contemplates that possible future.

In our circle: a 20-something not-out-yet sibling, a pre-school teacher who holds onto a fortune reading about their future lover, a straight passing enby surviving the corporate ladder, an academic estranged from their single mom who relapses into dating cis-het white men, a queer muslim urban planner, practically engaged lesbians and a very married gay couple who make award-winning flans.

Whenever I feel off the grid of society, I turn to the sacred texts of The Essential: Dykes To Watch Out For and find each one of our archetypes in these cult-classic characters. But I also notice extra cast members who don’t share an affinity in queerness: recently divorced, secret artists in the throes of academia, feminists who want to be late parents and adult children of abuse, all of whom have their own form of delayed adolescence.

Queer non-linearity exists beyond the imagination of cis-heteropatriarchy, not as a form of a protest but simply as being. If our existence serves as an uncomfortable reminder that straightness is a colonial invention merely a blink old and that compulsory heterosexuality depends on us to comply to create a labour force—these are symptoms of the system’s own unraveling, not our purpose. We are here because in our existence that expands the universe itself, we have always known we deserve joy and have consulted with grief to embody this euphoria.

In an interview with DMAG, Alok Vaid-Menon speaks of being perceived in a genderqueer eternalism: that we are, at once, a futurism beyond our present and also a pre-colonial artifact. In my non-linear travels, I find ancestors who take on the same form and find them again in the present in other lives. It affirms to me that we will exist again in bodies in the future by different names. And when they meet the deep grief that comes with the ways we shape the world—all of time will meet them there.