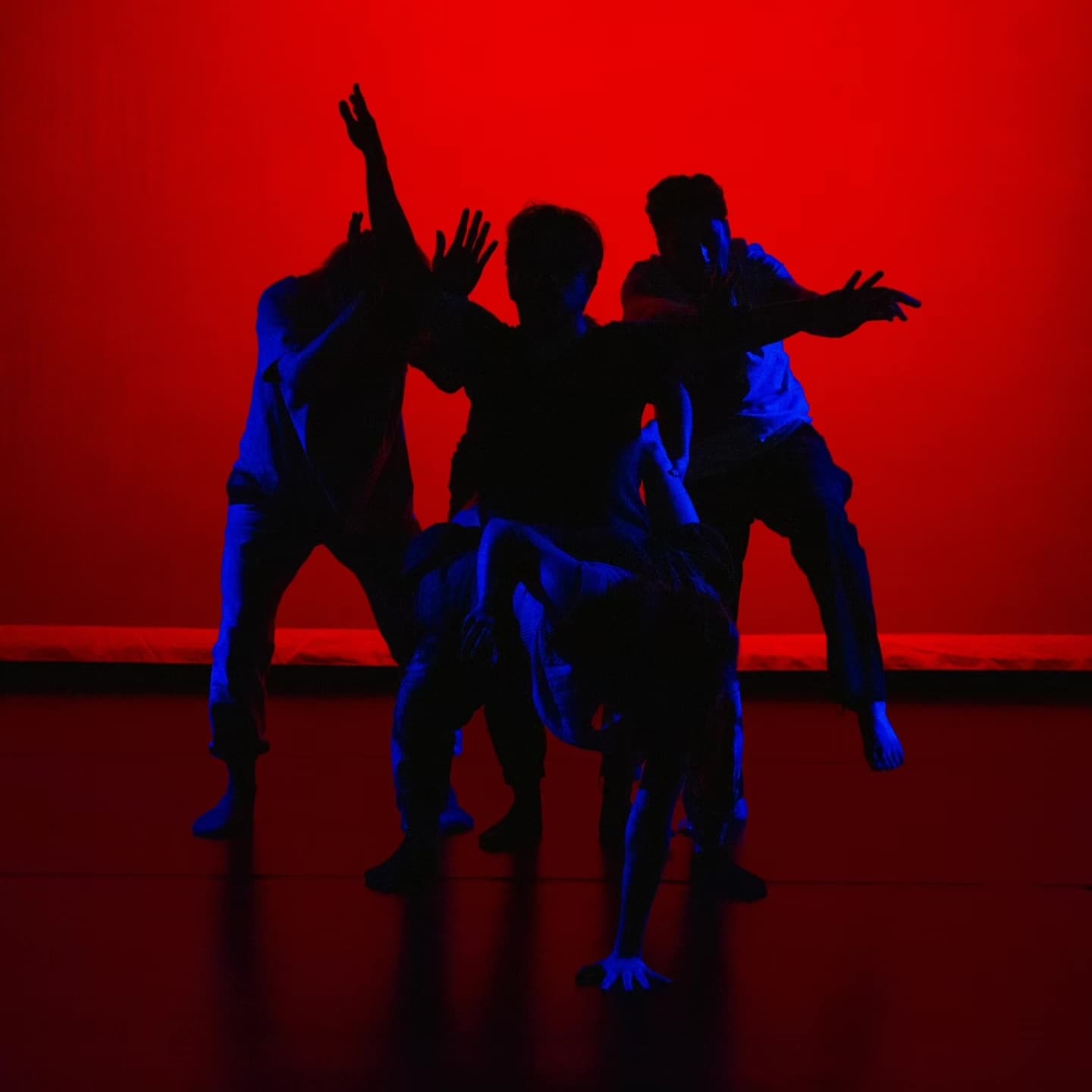

Becoming with the Ogre, the Phoenix, and the Faithful Friend

Benoît Lachambre and Ricardo Rubio Dance Through The Process of Eco-Somatic Drag

The credit for on stage photos are: Gloria Minauro / Isóptica

If dance is prayer, rather than performance, how can our micro-expressions serve as confessions? What characters—flora or fauna—can possess us through mimicry? Seasoned dancers Benoît Lachambre (Quebec) and Ricardo Rubio (Mexico) explore the intricate ways we choreograph our bodies into performance—replacing the fogeyism of the stage for the sacred.

In examining eco-somatic techniques, Benoît and Ricardo redefine posturing as shapeshifting: an authentic and transformative engagement that transcends the conventions of the 2D and brings us in conversation with the biota. In this reconceptualization the body becomes a tool, in service to greater cosmic forces.

Together, Benoît and Ricardo offer a multidimensional exploration of complex social identity and invite the reconsideration of our more-than-human existence.

Eco Somatic Trans-formism & Character Embodiment

Benoît

Shapeshifting is my passion. I focus on the effects, energy, and radiance. Recently, I’ve been creating “energy cradles” with voice, connecting with plants and elements, and exploring different types of polymorphic architectures of energy.

With the cradling of energy, I meet the different elements and the different life forms. And often what happens: if I sing to the plant, the resonance of the plant comes back. The sound comes back to me and the plant, in a sense—if I could put it that way—I feel the plant starts to shine inside my body.

They teach me, transforming my body’s knowledge. I’m curious about extended relational dancing, bonding with elements, and learning from them. The plant is the teacher and it starts to shift and manifest inside of me and transforms the knowledge of my body. Its shape, its fibers teach the body and transforms [it] from the inside— like the bloom of the coconut tree.*

Collaborating with Ricardo is transformative. Now, things are starting to happen more in the moment. Like today, when [my friends and I] went to the volcano, we made a little circle on the cold lava and the lava started to shine so strong. The heat of the lava enters the body and says in a very sacred moment, “Now you need to pray.” I surrender to the experience, letting it guide me. I have to yield to what’s happening.

Yesterday, I felt connected to a jaguar spirit in an ecstatic dance ceremony. There was an emblem sculpture of a jaguar (Chaquira) and I took off my shirt, I was full of sweat and performing the energy of the Jaguar—shaking the peyote energy and in a trance. I felt like I was hearing a certain spirit, perhaps the jaguar itself. It’s not about choreography, but about intuitive response, prayerful movement. I’m learning humility and service through this process. My dance practice is more and more about prayers so we can acknowledge the forces that are coming to us and how we can serve the forces. So the idea of choreography is more as something that must be done.

Ricardo

For me, [the] stage is either this concrete space or a very abstract and sensorial space where my soul—which is my anima‚—can flourish and can give me some information that can coexist with this reality.

It’s not this masculine power to control but this immense power to shapeshift and transform myself. For traditional dancers, it’s always a quest. We often find theaters restrictive due to many rules. The stage needs rethinking. Every artist should go very deep into their soul to see what they do in this space. What’s the sacredness of being there? Our dance has a ghost behind [it] that triggers the question.

Bodies

Benoît

When many bodies—each serving complementary purposes—unite, they collectively hold the knowledge that needs addressing. Surrendering individuality collectively, serves a greater purpose. In ecstatic dance, each person serves a purpose. Each did their part, I did my part and my part led me somewhere. I had to resolve something personal, lay down and heal about what I resolved. I knew it was time to lay down at a certain point. In that moment, I felt some of my ancestors might have begun to heal through my body. Someone came up behind me and clapped a few times and when the clapping stopped, it passed through my body and stopped the intense moment I had gone through. A man sitting next to me witnessed what I had experienced and remarked, “Yes, that’s how it is.”

It became obvious that there was another purpose outside of “just” dancing. As playing bodies, choreography goes beyond patriarchal consumerism; it serves transformative and collective purposes, going into other dimensions and serving something greater than the individual. Surrendering to this, trusting it serves a global purpose. Now my question is: How do I proceed with art-making with knowledge of all of that.

Posture-Deception and Deviance

Ricardo

The way people think about posture can be likened to the interpretation of a painting; as cultures, we’ve established notions of what’s considered good or bad. However, it’s not as straightforward as it may seem. For instance, Western society now has decided that being different (read: individual) is better than being similar—there’s a desire to explore something “different” and something “new.”Whereas some other cultures have so much fun with and respect for similarities. I find that being like my ancestors [allows me] to be a better version of myself. I’m happy looking like my grandpa or imitating my dance teacher. There’s immense wisdom in these postures inherited from our ancestors. It’s interesting to see both ideas of similarity and difference coexisting in traditional dances.

The posture is a path to go back in time to connect to ancestry. Our gestures are our grandparents’ gestures, our ancestor’s gestures. I cannot get rid of them. Every time I mistake myself for being “myself,” I am constantly met with a thousand of different versions of others like me.

Being myself is a negation of the past and the future. Biologically speaking, the body doesn’t understand true or false; everything is real to it. When a body assumes a posture, this, for me, is when it becomes interesting in dance. That posture might have been imposed on that body—it’s not their real posture, not what they want to do or what they are meant to do. While the mind may accept it, the body often rejects it. And not only the mind—every time we do a posture, our organs react to it: my liver, lungs, and heart have a specific point of view about that posture.

As a dancer, I’ve encountered instructors with differing methods. For instance, there was a small teacher, much shorter than me, who repeatedly urged us, “”Do as I do, imitate me, imitate me.” I was in a state of shock because we had such different bodies and I could not do what he wanted me to do. This experience prompted an ontological question: Is it better for me to memorize what other bodies are saying, other postures, or to acknowledge what my

posture is saying? Ultimately, it’s every individual’s right to decide whether to follow another person or listen to their own body.

Benoît

The pelvis, a dynamic structure, is intricately designed to receive force from the earth and effectively distribute it to the spine. This natural skeletal posture enables our bodies to efficiently absorb and utilize this force, allowing us to access our full potential and comprehend the underlying messages it carries. Posture plays a crucial role as a receiver of both force and messages. If we block our bodies too much, we hinder our ability to receive, potentially leading to anxiety.

We are designed to receive profound messages and engage in dialogue. This notion resonates in the intricate design of our bodies, particularly in our posture and the physical manifestation of our skeleton.

What are the ways that we, as individuals, can meet our strengths by opening our bodies so we can walk our path? Various bodies walking various paths. Each of us—despite our singularity—receives and is capable of receiving information, although we also can block it. Where one person may be closing off, another might be opening up, suggesting diverse pathways of reception and understanding.

The credit for on stage photos are: Gloria Minauro / Isóptica

The credit for on stage photos are: Gloria Minauro / Isóptica

Sacred Performance & The Role of the Body in Dance As Prayer

Ricardo

Quiero clarificar las causas, ya que con frecuencia observamos que las palabras perecen en nuestra sociedad contemporánea. I want to clarify a few points because in contemporary society, words often distort our intended meanings. Much of this revolves around clarifying words or techniques stolen from institutions such as the idea of “the stage”, and “praying” which is so embedded in religion and have little to do with everyday life.

What I find both intriguing and concerning in contemporary prayer practices is the absence of the body. When we engage in prayer from this perspective, it’s as if we want to solve something from the body. As if the body was wrong and not aligned. I agree with Benoît that praying has come to be seen in a very capitalistic way: if I do something (pray). I will get something. Like paying to get something and becoming frustrated when our prayers do not come true. We suffer from that because we are asking “the outside” to do something that is our responsibility.

I propose a different approach to prayer: to have an intention and to allow this intention to work inside of you.

The Limitations of the Stage

Benoît

I’m not attracted to the stage anymore. Dealing with the mass of the audience has become challenging. It’s hard to feel what each individual is doing there. On stage, my ego becomes very strong. A habit developed over 40 years of performing. I find it difficult to surrender on stage compared to other settings.

In settings where people are arranged in a more open, circular manner—allowing for interactions with different people—I feel more at home. In a more rounded place, I can let go and [be] improvisational. I love the term that Ricardo opened the conversation with: fractal. It’s amazing to get your body subdivided into an infinite empathy of what is happening.

In my European heritage, the stage has served the king, creating a personal conflict for me. I say, “Oh no, I don’t want to be in service to the human king that’s ruling everything nor to the hierarchy of power that is patriarchal.” I’m trying to shed away from this so I can get rid of that anxiety. Instead, I’m in service to something bigger than the power of the king, court and capital.

While I acknowledge some beautiful forces in stage performances, my personal politics lead me to view the stage in a negative light— a place of pressure to be perfect and seek approval. This is my personal struggle, shaped by past experiences but as these are the realities that I’ve formed. I recognize that others may have a more positive relationship with the stage. It’s a crisis I must navigate to move forward.

Ricardo

In performance, we’re not only observers. Dance speaks so much to our animality—and it speaks so much to our mammality. I invite people to a state of perception rather than receiving, which is a kind of passive sensation. The stage has emerged out of the building up of strong concepts like “dance,” like “contemporary.”

We create these whole entities—like Gods, with infinite power—and we forget that we create those things.

Ricardo

Ricardo

We’re the creators of the stage. It’s where big action may happen. It’s not this space where the lights are—it’s where the fire is, or it’s where the moon is, or it’s where we are all together. It’s where I find strength, not in controlling, but in shapeshifting and transforming. The stage isn’t limited to theaters; it can be anywhere, even at my home or in a restaurant. Anywhere your soul can flourish.