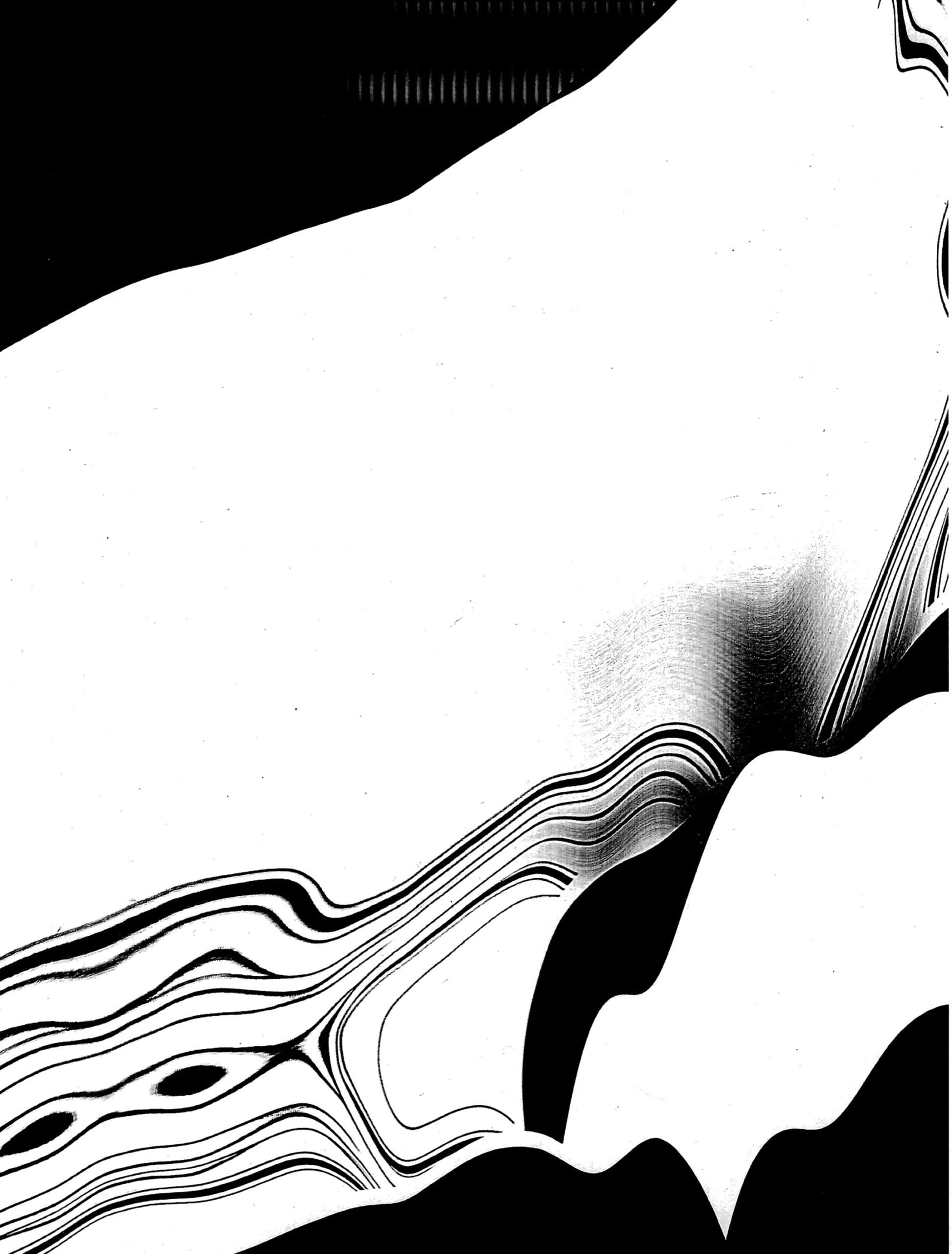

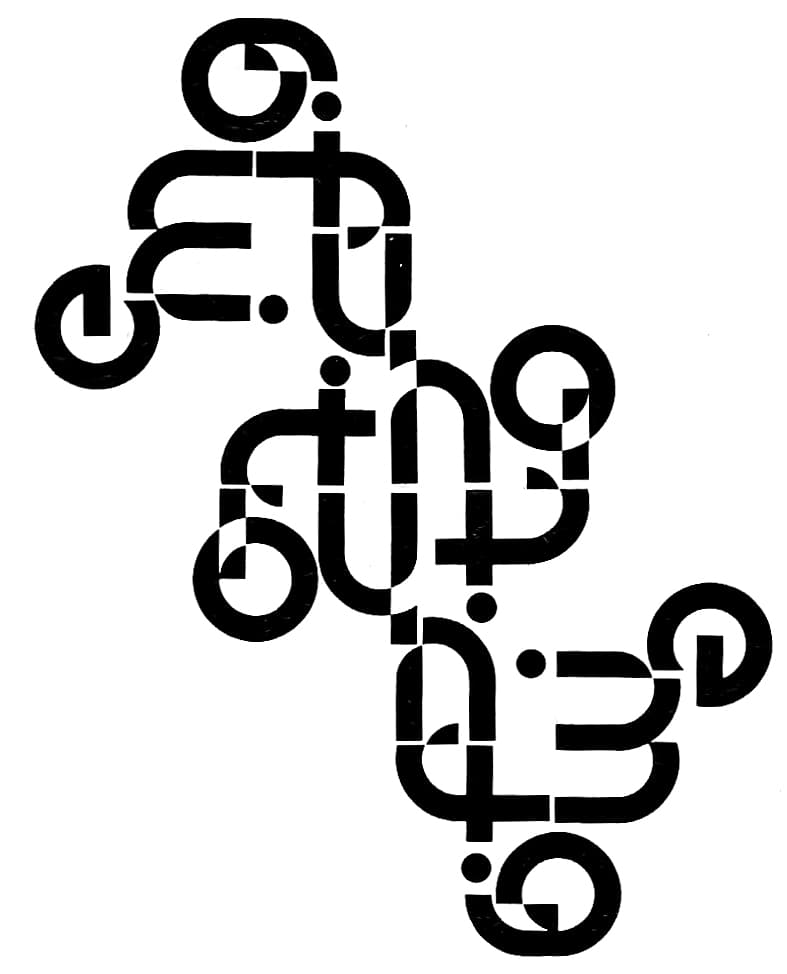

Page 104 from Surface Tension by Derek Beaulieu, published by Coach House Books

Page 105 from Surface Tension by Derek Beaulieu, published by Coach House Books

About a decade after the French Revolution, a boy walked out of the woods near Saint-Sernin-sur-Rance. He had been spotted by villagers and caught by hunters a few times in the years before. But he had always run away to the woods again. This time, however, he came out on his own. And he remained in society until his death in Paris three decades later.

Victor of Aveyron, or the wild boy of Aveyron, l’enfant sauvage, couldn’t speak when he first emerged. He was covered in scars. He only ate raw foods. His hair was gnarled. He was so used to the cold that he would venture into the snow naked, in joy. He was thought to be about 12 years old and may have lived, alone, in the woods from the age of 4 or 5. Was he lost in the chaos of the Revolution, or something more mundane? His origins were never determined.

As news of his feral upbringing spread, the naturalists and philosophers of the Enlightenment—granted institutions by the Revolution—became fascinated by Victor. For many of them, language was what divided the “distinctly human” from the animal. The natural history of the human needed to move beyond mere speculation. And here was someone of both worlds to study, or something trapped between neither: a human without words.

Page 7 from Surface Tension by Derek Beaulieu, published by Coach House Books

Itard’s teaching relied on a common assumption about language: that it is primarily communicative. We speak in order to communicate with others. To transmit our intentions, inner expressions, and desires. As infants, we want food, an embrace, or a toy, and we learn to utter a word that stands in for the object, so that others might accommodate us. We learn language in order to communicate. We replace pointing with words. Or so it’s thought.

But teaching Victor by attaching words to what he wanted didn’t work. He would point, and exclaim, and gesticulate his desires when he had them. But no words were ever welded to his pantomimes.

And then, suddenly, one day, he uttered a word. But the first word Victor let loose – lait – didn’t come when Victor wanted milk. After Itard heard the word and poured him some milk, Victor didn’t drink it. He didn’t want milk. But Victor was overjoyed that Itard had recognized it. He was overjoyed at the recognition of having produced an abstraction shared by them both. And the joy overran his body. A joy that wasn’t limited to fulfilling a need. An immanent joy of abstraction.

Victor would practice rolling the word “lait” around all day, and even at night, alone in bed. It wasn’t a matter of him wanting milk. He wasn’t communicating his desire for it. He wasn’t directing a request at anyone. There was just something in the pleasure of it. In producing the shape of a sound fitted to the shape of a concept. .

What the philosopher Suzanne Langer describes as the joy of bringing a concept to mind, rather than an object to hand.

That activity isn’t aimed at fulfilling an internal need tots have. They’re not trying to communicate, although, communicative partners will be important later. But first, they play with language. With its acoustic tendencies and forces—and its forms of feeling. Infants have to ingrain a language’s forces into their body, to make it a habit. As they tense their muscles to make air vibrate, using their cavities for resonance, a complicated inner choreography is taking shape. And so they babble in their cribs, without any partners, through the pleasures and challenges of doing so.

If you’ve ever learned a foreign language, you know how much the habits of your native tongue resist. How much the new sounds have to be practiced to be produced at all, let alone in fluent sequences of sounding. Eventually, you hope, sound after sound, word after word will be strung together effortlessly., aAs though each were naturally attracted to the next. And in a way, it would be, as if the rhythm of a language is one of the forces pulling speech together. Like gravity, it’s a field. Multiple rhythmic forces are acting on a sentence at any given time.

There’s a glimpse of babbling pleasure in Victor’s enjoyment of the word lait, detached from any use. An aesthetic pleasure. Unfortunately, And like most cases of children brought up without language, Victor never learned to speak much beyond this. A few words, some simple actions

One of the critical thresholds for language acquisition, it seems, is babbling. Victor began to babble all “too late”— only babbling words, and not their more molecular phonemes. The forces of a pre-syntactic and pre-semantic field to explore language as we know it now, were not. It’s a phenomenon we’ve noticed in studying chimpanzees and apes. While some have, through extensive human effort, learned a limited vocabulary and basic syntax, they never play with the sounds of language the way infants do. Their language never lifts off beyond a narrow, immediate, communicative use.

Most people become fluid language users in their adulthood. Most day-to-day use of language is for its communicative purposes. Commands, requests, expressions of state, excuses. But many mistake this destination for its origin, forgetting the open-ended enjoyment that launched us into language use. And maybe rightly so. A doctor who babbles when you want a medical diagnosis is a breach of the professional responsibility we rely on to live together.

Artists bear few such responsibilities.

derek beaulieu is a Canadian poet. He’s written a work titled Surface Tension (2022). It’s a small book. But saying it was written may confuse some readers. There are few sentences, fewer words. Even the letters will begin to vanish into syntax and semantics.

Like all great methods, beaulieu’s is simple. Take some letters, put them on a rubber sheet and bend them. Stretch and rotate them—this way or that. Spread them on the surface of water and drop a stone, rippling their surface. Put them on a metallic sheet and pound them, leaving the trace of your force encountering their resistance. When—after transformation—is a T still a T still a T still a T? When does it snap and break symmetry?

There are precursors to beaulieu’s topological variations, like sound and concrete poetry—from Russian zaum in the 1910s to American L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetry in the 1960s. Most of this poetry rejected the idea that poetry expressed a poet’s inner feelings. The poet’s job wasn’t to feel something, put it into words, and communicate it to a reader. There was more going on with how language worked, and they wanted to descend and swoop across those more molecular levels.

That doesn’t mean beaulieu’s work is unmoving, unaffective, cold, or formal. Far from it. By freeing letters from themselves, by re-placing them in a field of visual and sonic forces from which they emerged, beaulieu finds other ways of making letters move. Other ways, like Victor, to generate pleasure in the significance of their form. beaulieu experiments with what conditions the coherence of a letter, of what makes their surfaces tense or diffuse. Like a chemist dropping a surfactant in a solution, he experiments with materials and forces.

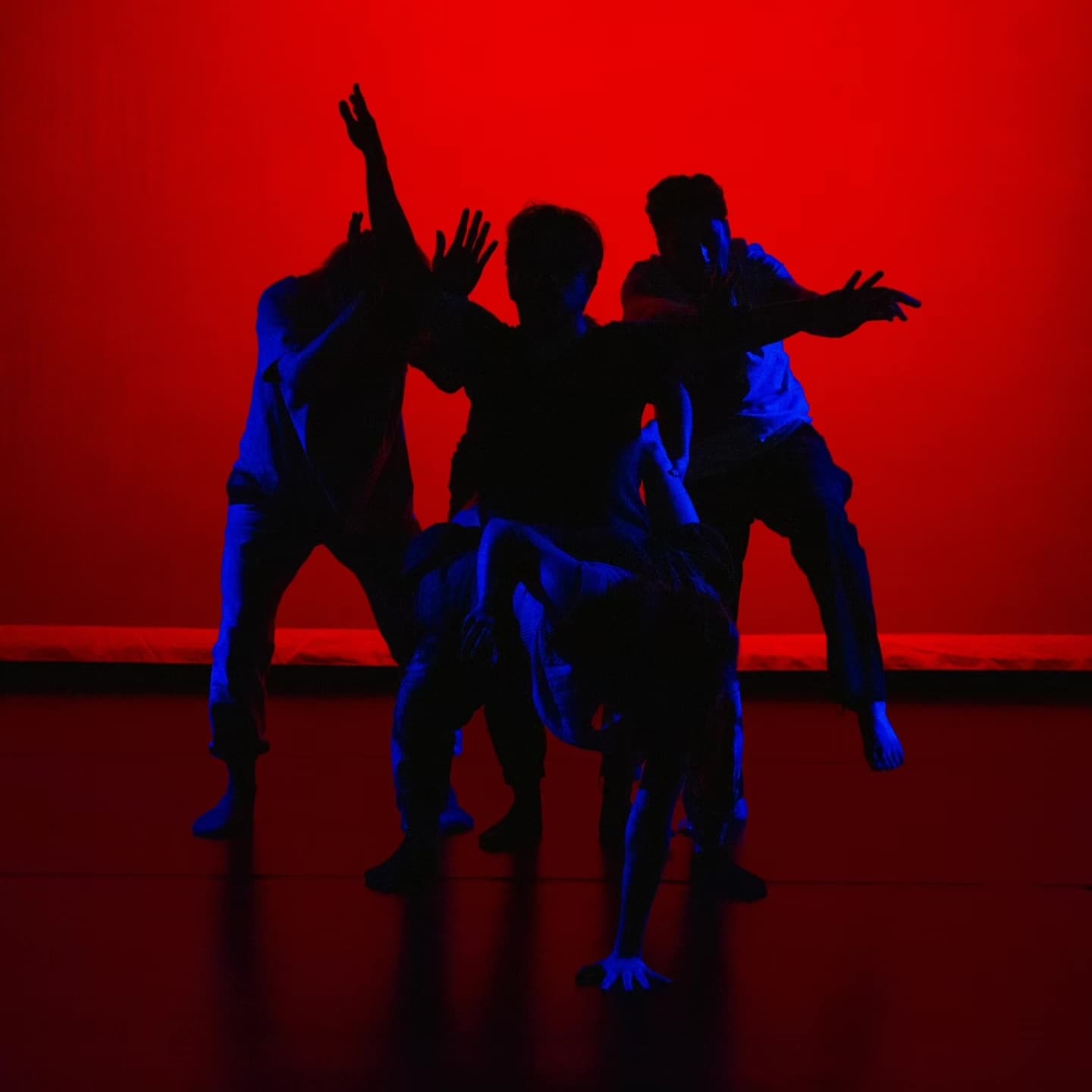

Letters and elements of letters: Dart. Flutter. Strain. Reading, we follow the movement of letters as they swoop and swerve, tremble and seize. What looks static at a glance—just marks on a page—is endlessly dynamic when perceived in time. All media is interactive, since it takes time to engage. The letters produce the semblance of movement as we trace our eyes and ears alongside it, even if the letters don’t actually move. That movement, like a baby’s babbling, is a form of feeling. It might not be as familiar as what we label as emotion, but that’s what makes beaulieu’s work work.

Page 61 from Surface Tension by Derek Beaulieu, published by Coach House Books

Letters can’t be angry or sad; but they can pulse, just as anger pulses, and they can wither, just as sadness withers. Of course, that can be reversed—anger can wither, just as sadness can pulse. That’s what makes it a form, and not a feeling.

Take the way the letter W slides and glides over a sharp crest, before hitting a second peak from which it suddenly vanishes in a void. Abstract, that oscillation could diagram any number of other experiences—sounds that rise and fall and rise before suddenly dissipating, leaving a ghostly echo, like the cliffhanger at the end of a series finale. Every letter provides a topology of variable form. Its surface can be tensed or diffused to produce a range of expressive variations. Or take how the shape of a J swings and rockets up a smoothly accelerating curve of vertical intensity. Reverse the movement and watch it fall precipitously but catch itself before impact, gently swinging inches from the ground. Vary the straightness, vary the angle of the curve, vary the more likely direction movement will be traced, and the form of feeling will vary too. All letters can do this.

Letters leave strange marks. Language is a strange tool.

We live in a time when, for many, writing makes up a large part of their professional and personal lives. A time when the pressure to produce and scale language has led to machines that can do much of it for us, however strange those machines themselves are. Most uses of writing are instrumental—we know what we want to get from using words. An aim, an end, efficiently achieved. We turn language into a habit, ingrain it in our body, and expect results when we deploy it. But maybe we assume we understand how these strange marks we’ve imbibed work a little too quickly. How these incorporeal ghosts make our bodies tremble and stutter.