The NPC: An unplayable character for unnarratable times

An exploration of a nebulous and evolving archetype

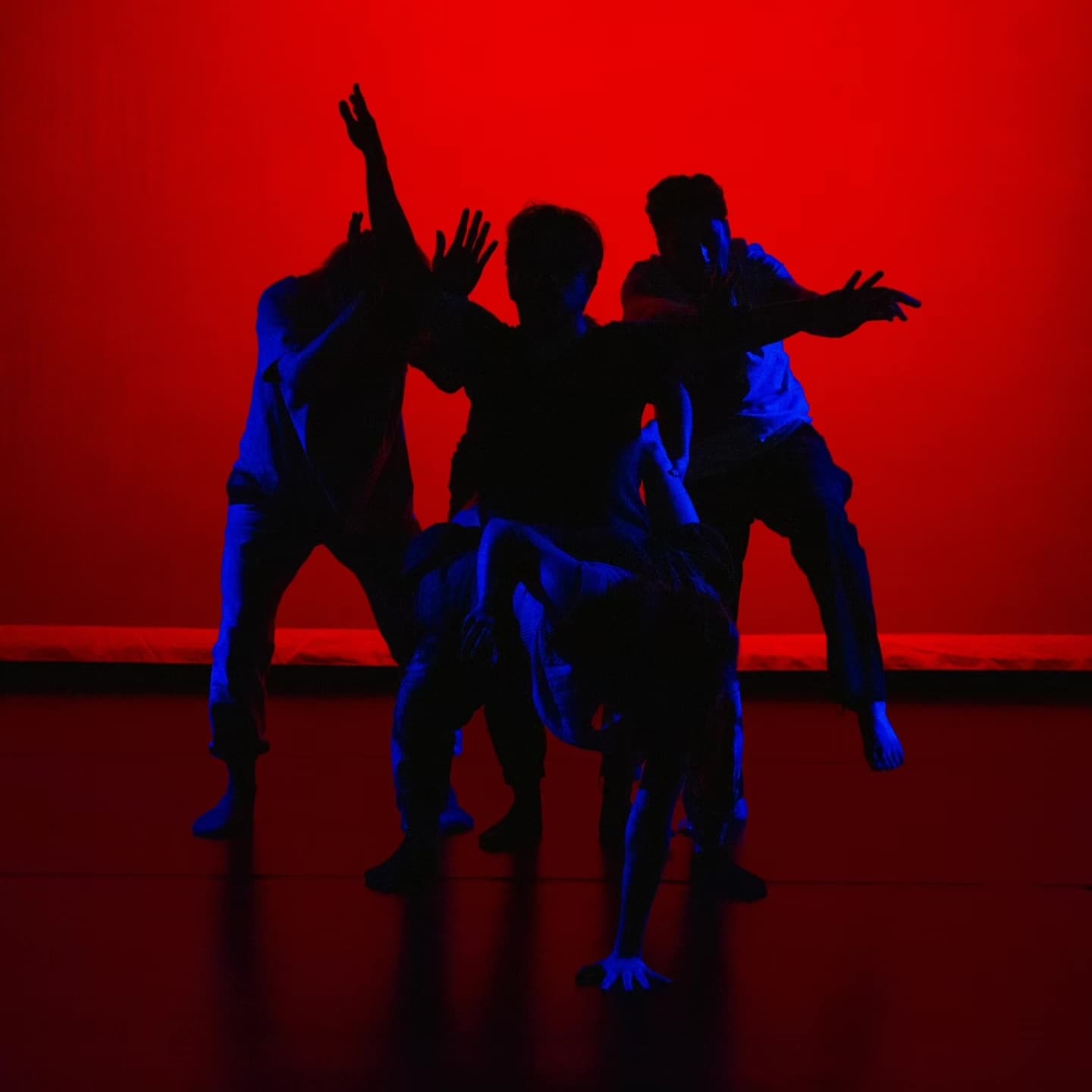

Artwork by Kadrah Mensah

My date introduced herself as an NPC. By this, she meant she knew neither the bride nor the groom; she was just with me. Recognizing myself as Player One induced the tension of a gamer trying not to die. My jaw tightened, back strained, shoulders raised. I remembered a wedding months earlier, where I was the side character, my partner’s date. How relaxed I felt under no pressure to be anything other than there, smiling, complaisant, not too drunk. Unimpaired by the anxiety of agency, a Non-Player Character (NPC).

Artificial, not intelligent, the NPC is a side character that can’t be controlled by a user. Limited to a set of predetermined behaviours and scripted remarks, an NPC is triggered by interactions with live players. Akin to the old theatre term, fifth business, NPCs hold minor roles that, nonetheless, drive the plot.

Sometime around the reality rupture that was 2016, NPC was hijacked from the worldbuilders. It became a popular way for libertarians who value maximum agency to disparage liberals who support the current thing. Soon NPC became a label you could throw at anyone lacking reflexivity or who can’t do critical interpretation. As the aesthetics of insults go, NPC was beautiful. Potent, grand and utilitarian. In three efficient letters to dismiss your detractors the way an athlete dismisses sideline hecklers: until you enter the arena your opinion counts for nothing. You’re a non-player. The NPC conceit conjured a bizarre theory of everything drawing on occult mysticism, pop psychology, and the simulation hypothesis. To summarize: Given the scarcity of souls in this video game, some of you are basically furniture.

NPCs were said to have no inner voice. To be called one was to be called not subhuman, but humanoid. It was mean. Crisply dismissive. Very funny.

A phrase’s cultural connotation moves from descriptive to pejorative to aspirational in the time it takes to cringe. A few New York Times trend pieces later and NPC is widely known, if polysemous. Though its derogatory use is still in play, NPC is no longer reserved for 4Chan types dunking on NBC News types. Instead, in a surprising feat of linguistic upcycling, NPC was repurposed as an expression of modest reserve. The term was now versatile enough that self-identifying as an NPC at a party gives a slightly self-effacing charm. The insult implying an absence of internality became a signal of self-awareness—an endearing move to acknowledge one’s role within a particular social dynamic. The appeal of this use-case is obvious. Only someone with Main Character Syndrome (the internet’s way of saying narcissistic personality disorder) wants to be centred all the time. The rest of us oscillate, taking turns between being in the mix and laying in the cut. At a public gathering, the self-identified NPC softens the atmosphere. As a personal refrain, to say, “I’m an NPC” is a gentle reminder to self that “it’s not all about me.”

So resigning to NPC status has become desirable; some say emancipatory. You give yourself a gift: temporary relief from the burden of protagonism, a chance to simply be and observe without the weight of narrative responsibility.

The connotational shift of the slang term coincided with a proliferation of NPC iconography in internet culture.

Raised Online sold a generic hoodie with “NPC” written in collegiate lettering. The concept was an exclusive sweatshirt “made for everyone” according to the brand: the three-lettered varsity applique, a coveted badge of populist detachment.

Total Refusal, a Vienna-based media collective, examines the lives of NPCs in virtual worlds. One of their documentaries follows four workers—a laundress, a stablehand, a street sweeper and a carpenter in the video game Red Dead Redemption 2—narrating their mundane lives with Herzogian solemnity. Over the course of the film, it’s revealed that these workers don’t actually get much work done in their virtual world, suggesting their idleness might be a synchronized act of resistance.

When NPC live streamers like PinkyDoll and accelgirl went viral reciting robotic responses in exchange for rose bouquet emojis, they incited real joy, confusion, and concern over the brittleness of human minds in algorithmic culture. Alex Quicho, however, in her work on technologies of girlification, says this incarnation of the NPC is an “other type of angel, the super-evolved brainless doll slurping dollar-pegged ice cream.” She tends to the machinic, which is to tend to the collective. Melded to the networked superintelligence, the individual is flattened to a node of airy thinness. This is not atrophy; it is expansion.

Somewhere between an Infowars meme contest and the latest Yeezy drop, the NPC transcended its pejorative function; it became the object of ritual embodiment. There are make-up tutorials instructing how to recreate the uncanny NPC face, quizzes you can take to find out if you’re an NPC, and online courses where you can learn how to move like one. In its many manifestations, the NPC is the archetype of an era that aspires only to be mid—a people that wish to blend in, a culture that celebrates not the hero nor the villain but the chorus.

Dancing like an NPC is now a trend on TikTok and other user-generated video platforms. Viral clips like ‘Going to Walmart as an NPC’ and ‘I went shopping with my NPC girlfriend 💀’ feature dancers, moving through the real world, emulating the gestures, gaits, postures and facial expressions of video games characters from staples like Grand Theft Auto, The Sims, Call of Duty and The Elder Scrolls. Strictly speaking, they draw on movements from playable characters too, but signify the state of automatic oblivion associated with the NPC archetype. These videos are mesmerizing:

The dancer hovers weightlessly in a T-model preparatory pose before jerking into a grammar of ungainly hand waves, sudden crouches, and exaggerated grand jetés. Their transitions are abrupt—sweeping turns on impossibly sharp pivots. The body deforms, snapping from one orientation to another. They strut, arms-swinging with a nothing-to-lose gait like a brute looking for a fight. What the choreography lacks in purpose and direction is also what makes it so resonant. The NPC keeps going, detached from the chaos surrounding them. Continuous rhythmic strides are unthwarted even by the clipping of physical obstacles. For a coda, they walk endlessly into a wall, their countenance unchanging. Marching in place, their footwork presents a familiar absurdity—exertion with inertia, effort without the possibility of achievement. Their gestures are the somatic expression of brain fog calibrated to the tone of that dull hum people report. This is a dance about persevering through stagnation, yearning for renewal. The NPC seeks what anyone seeks when they’re stuck: a reset.

Inevitably, the NPC archetype arises in response to the sustained anxiety of existing in metacrisis, a theory of everything people worry about. The underlying dynamics of the metacrisis are a Jeremiad list of global existential challenges: prolonged pandemics; climate risks; global conflict, war and genocide; economic precarity and resource scarcity.

These are compounded by crises of individual meaning, epidemic loneliness, and despair. All of which are further clouded by an epistemic crisis so normalized it’s hardly talked about anymore: information overload; eroded trust in science and journalism; meme warfare, misinformation, and engineered persuasion; psyops and cyberattacks against citizens; routine identity fraud attempts via text message.

Kadrah Mensah, a Toronto-based artist who also works as a content strategist at Snapchat, explains the NPC as a symbol or symptom of a pervasive feeling of obsolescence. The experience of being overexerted and falling further behind is “causing a circuit to break,” she says. “We’re frying.”

“We’re biological, we’re degrading,” says Kadrah. “What does it mean to be a living thing that is dying while the machine moves forward?”

Through 3D animated video works and sculpture, Kadrah’s 2023 exhibition, “surely you’re joking” attempts to “articulate the existential chaos of having a body in a technocracy.”

The exhibit’s central installation is an Air Dancer with NPC Wojak face (the way NPCs are represented according to the graphic standards of meme culture). The inflatable tube man, best known for his work promoting car dealerships, is the original NPC, an animated body subjugated to a way-finding device. However much it appears to hurl itself, the Air Dancer is stuck in place, while everything around it moves forward. Kadrah dances with the character, matching its distinct flailing pattern, as a ritual to destress while preparing the exhibit. Dancing, she says, helped alleviate her own anxiety of obsolescence as an artist who is working in a time when new ways to generate synthetic visual culture emerge daily.

To create the NPCs in her video works, Kadrah had to learn the fundamentals of 3D animation. She admits she chose this medium, in part, because it seemed like the skillset had a moat, separating it from the encroachment of AI art generators. But just weeks before the opening of “surely you’re joking,” Blender announced the first text-to-3D-model plug-ins.

Animating 3D virtual characters is not easy. As Kadrah says, it requires you to deconstruct movement. When you model a 3D character, its body is represented by a mesh, an empty bag sculpted to the character’s geometric form. It’s the outer surface only, without mass or physiology. “It has no concept of movement,” says Kadrah. “It doesn’t know how to walk.” Nor is it subject to the laws of physics.

The 3D character is created in a vacuum—without gravity, friction, or air resistance. This kind of inside-out physics known as kinematics, a math that describes position, velocity, and acceleration without considering the underlying forces that cause their motion.

The mesh of the body is bound to a rig, the character’s skeleton. The animator has to assign influence to specific bones and joints in a hierarchical order, so the character’s body parts connect and rotate in a cascade of motion. The results look strange because they are. You have this internally coherent body of physics that, while it appears to hold itself in relation to a universe, is unmoved by external forces.

When dancers on TikTok imitate NPCs, they’re enacting how their bodies would move if they were placed on a rig. This is key to understanding the desirability of NPC role play. It’s the fantasy that you might move through the world without feeling exhausted by its hefty pressures, unfazed by the chaotic metacrisis around you.

Just as it’s difficult to transpose the natural movements of humans into video games, so is it difficult to copy NPC mannerisms over to our physical world. Bringing this logic out of the virtual and into the real through dance is a virtuosic feat. Manipulating oneself to move within the kinetic limits of computer graphics is a show of remarkable strength and poise.

Through their lexicon of visual sleights, the NPC dancers show what it might be like to be kinematic, loyal only to your own bones, unaffected by outside information. They appear to levitate; they glitch, distorted and disjointed; they’re precise, stable and consistent, as if tethered to a rig. As a style of dance it may lack delicate finesse, but it boasts conclusive control.

The human body, as with the project of technology, has something to prove to the world—that it can manipulate physics to do what it wants. Both technology and dance are media for testing and exploiting the fundamental laws of nature.

NPC dancing belongs to a lineage of popular dance moves inspired by technology and industry. As the McLuhanian aphorism goes: “we become what we behold.” We’ve done the robot, the locomotion. The moon walk, if only in name, commemorates the technological triumph of the space race. Voguing, with its serial striking of static angular poses, evokes the camera flash at a fashion photoshoot. Popping and boogaloo draw on movements from classic cartoon animation. Each of these dances literalizes and subverts its own technocultural fantasy: to be powerful and efficient, to be glamorous and immortal, to be frivolous and fantastical, to do the impossible, to be liberated of earthly constraints.

The NPC dance performs a fantasy of ordinariness and anonymity.

The French Ballet performs a fantasy of what it is to be courtly. In its formative years, King Louis XIV, himself a dancer, established standards of technique and performance that reflected the poise and self-control valued within the Royal Court. If Ballet adopted a style and etiquette that reflected the king’s postures back to the king for the king’s pleasure, choreographing a coherent relationship of power and worship — NPC dancing for TikTok is about presenting the gestures of digital media back to the computer in ways that make our subservience to machines more legible to them.

The 3D animator’s stylus impresses itself all over GenZ’s signature dance moves. Though they may have IRL origins, moves like “the floss” got popular by way of the game Fortnite. They made their way onto TikTok as part of wider trends or challenges. Over time and iteration, the moves evolved into longer choreographies and were sometimes reincorporated back into the game. Eventually, it starts to look like a reciprocal cultural exchange is happening directly between video games and social media. Humans are relegated to intermediary status, oracular bodies and hands needed only for a brief phase of manual transmission.

As Joshua Citarella put it on an episode of the New Models podcast, “If you look at TikTok, your body is literally animated by the algorithm—it tells you how to move yourself—and you end up dancing for this abstract formulation of capital and algorithmic recommendation.”

The abstract formulation Citarella describes is what his colleagues Lil Internet and Caroline Busta call Platform Physics. These are the hard-coded workings of platforms—their inherent user interfaces, mechanics, affordances, algorithms, and incentives—that determine what kind of content is made and how it gets circulated through the network. Different kinds of physics produce not just different kinds of content, unique meme templates shaped to fit the platform’s Overton window. The platform physics also produces different kinds of audiences and criticism, and most obviously: different kinds of authors and postures.

Platform physics shaped the mode of faux-modest gratuitous narcissism that would have an artist launch their latest painstakingly created opus with a selfie and the conventional caption: “So I did a thing 😏”. These are the same physics that fashioned “Felt cute, might delete later 😜” and “Am I doing this right? 🤷♂️”. When a serious artist performs the latest TikTok dance, attaching the caption, “Had to hop on this trend 🌟”, it’s because they really had to. It’s physics.

When the physics are inscrutable, you get a corresponding mythology; folkloric divinations about how the algorithm sorts and shares content. The idea of manipulating the platform’s invisible inner workings to improve the visibility of your posts is so enticing it’s grown into a whole genre of content about content. Creators advise creators with unverified tips about how to get better engagement. They aim to decode the algorithms, reverse engineering pseudoscientific hacks to exploit the mechanics. Their guides claim to reveal occult secrets about when to post, how quickly you need to respond to comments, and why you might have been penalized or shadow banned.

The distinction between pandering to the algorithm and hacking its mechanics is trivial. One’s creative expressions become part of a nuanced tactical game. Thriving on social media without demeaning one’s own enterprise demands a sophistication with the dark arts of online irony that’s usually reserved for meme accounts.

The Montreal-based artist, Jessie-Jamz Ozaeta aka Lil Lonely, is in his “NPC era” according to a recent instagram post. It’s a joke about pivoting to take on a “normie job” to supplement his art practice. “I’m trying to do commercial work. Or something NPC-ish” he says. NPC behaviour is near-synonymous with the cheerfully automatic conventions of customer service. In professional settings, you go into NPC mode.

Artwork by lil lonely

Consistent with the platform physics of LinkedIn, you present a flattened version of yourself. Jessie makes this process literal through the construction of his virtual avatar. “I just take a low-resolution image and slap it on a 3D plane,” he says. “My work is very ephemeral. It’s just a joke on me.”

Jessie is a rare artist whose work directly confronts the problem of posturing in a time when everyone with a smartphone exists in a state of moral contradiction. He says he mocks his own “ego-related hypocrisies.” His art deals primarily with narcissism, and the inevitability of displaying narcissism in a society where the idea of celebrity is entirely elastic. Where self-promotion is simultaneously encouraged and condemned, the pattern of building people up only to tear them down is discernible even at the smallest scale. Jessie’s work exposes the trappings of platforms whose physics propel the most sociopathic and self absorbed. On social media, Main Character Energy accelerates, perpetuates, and ascends. But harnessing this dynamic involves also enduring the nadirs of despair that complete the narrative curve. As in a trampoline, it’s the lowest point of depression when potential energy is at its maximum, before the kinetic bounce back.

Swinging between grandiosity and periods of internalized shame is a feature, not a defect, of the functional human artist.

Jessie employs humour as a direct tool to dissect the tissue of his own affectation. His practice involves rendering himself as a low poly 3D character. Lil Lonely is an NPC he “imprisons in a virtual purgatory,” doing the Pinegrove Shuffle, a TikTok dance, for all eternity. That Jessie names his NPC alter ego Lil Lonely could be partly read as a response to platforms that incentivize catastrophizing. By these algorithmic measures, it’s better to have “the worst anxiety ever” than to be a bit nervous (or a little lonely). A post about depression travels further than one about sadness. Destigmatized mental health disorders, now considered identities, further reinforce their own prevalence as content. Epidemic loneliness is alleviated only by the constant feeling perceived under surveillance capitalism.

“I put myself into my work as an ironic punishment for the things I do in my daily life that I find narcissistic,” says Jessie. “The work still comes off narcissistic, but that’s kind of the point.”

The contemporary artist’s operating environment is a multi-platform entanglement of forces and lures—systems on systems on systems—a complex of felt pressures and perceived bait. And it shows in some of the postures commonly struck by artists: demure, sardonic, scatterbrain, radical, moral, cool, aloof, erudite bibliophile, glamorous, struggling, shamanic, QAnonic, shadow-banned, naive, cyborg, edgelord, wholesome, sexy, hyper-masculine, divine feminine, feminist, not-racist.

There are moments when posturing becomes explicit. The tasks of crafting artist bios and gallery didactics are ideally delegated to curators, gallerists, critics, grant writers, and chatgpt. But the artist is postured regardless of who composes these stories. The reality is that many artists handle such tasks themselves due to the lack of a supporting infrastructure. Consider grant writing, the task of striking a fine balance of what you want to do and what you imagine they want to hear. “Tell us about who you are as an artist.” You’re asked not just to present your art, but to confess yourself, or a version of yourself you’ve built to survive the gauntlet of jurors you imagine scrutinizing your answers for compliance with the zeitgeist. The irony of contorting for an institution that is itself contorted by the purse strings and political whims of donors and board members—really does feel like dancing for the algorithm. Finally, it’s time to “Describe your overall artistic practice and/or vision.” Your hands that have molded clay, coiled wires, stretched canvas, and guided brushes—will now tap out a dance for the Arts Council: “My work is an exploration of the existential melancholy of non-player characters as expressed through text-based appeals for institutional validation.”

The NPC is fortified from the structured incentives propelling playable characters to fight dragons and chase shiny objects. Existing just outside of the parameters of plot progression, the blank-faced NPC evades fluctuations of good and ill fortune. While players are subject to variable vital stats—hit points (HP), stamina, and experience (EXP)—the NPC’s body doesn’t keep score. The NPC is stable, fixed in their strength, intelligence, and allegiance. Indifferent and invulnerable to the narrative arc—the NPC, rather than the villain or the antihero, is the true opposite of protagonism.

Calling yourself an NPC is a type of negative identity formation. It doesn’t say who you are; it says who you’re not. Like a figure-ground relationship, you articulate yourself by defining the negative space around you and abstracting yourself from it. As an NPC, you are: Not Player One. You’re not any player in this game. Not the main character. Not a good guy nor a bad guy, though your sense of self is oppositional. The NPC is defined against playability.

Rather than some conformist reactionary programmed to retort predictably when triggered, the NPC takes a stance of Non-Playability—a mindset, a firm attitudinal relation to the circumstances, a kinematic posture. This NPC is internally charged, unswayable, loyal only to their rigging, a kinematic self moving through the world motivated by their own internal math.

If its mesh is a vessel, the NPC is a wastebasket to store our collective anxieties about an era marked by capitalistic pressures, digital alienation, climate damage, political division, and obsessive identity formation. The applied symbols and reenacted rituals of the NPC archetype constitute a mythology for the metacrisis, an awakening from the dull languishing deep fried brain fog with new postures, new gestures of machine vitality, and new aesthetic techniques. The mood is of detached resistance rather than disillusioned resignation. Unlike main characters who respond to command, NPCs respond to stimuli, reclaiming agency from within its glaring limitations. However deluded by free will, playable characters cannot divorce from their preordained missions and milestones; their story is all but written, a matter of degree of achievement. The NPC however defies biography, rejecting the absurd expectation of narrative coherence, in favour of staying unresolved.