Eaidánis & Waawaashkeshiwag in Families and Constellations

A conversation between Dr. Alex Wilson and Nova Courchene

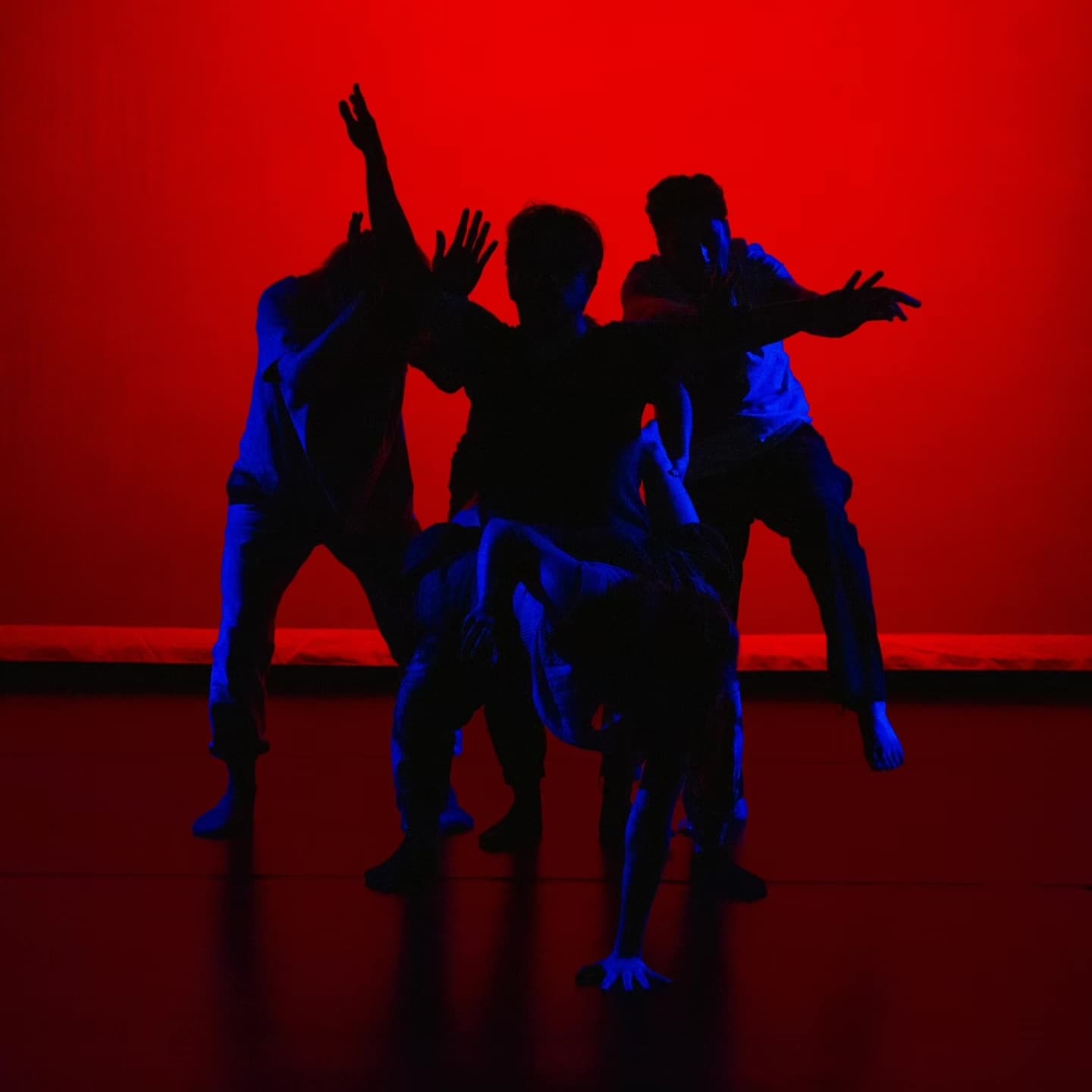

Omaagomaan

Photo credits: Kate Dalton

In the rich tapestry of Indigenous narratives across Turtle Island, animals serve as profound symbols, embodying intricate lessons, concepts, and wisdom. In creation tales, these beings precede humanity, engaging in deliberations akin to human governance, addressing resource management and problem-solving with sagacity. Within our oral traditions the use of animals in storytelling convey teachings and insights that resonate deeply with our collective consciousness.

Waawaashkeshiwag Wabano examines the Ojibwe creation story through the inner dialogue of Noozhe, the protagonist doe, who questions her place among the council of animals. Using her play as a catalyst for conversation about diversifying gender roles in a matriarchal culture interrupted by colonial patriarchy, Nova extends a gracious invitation to Dr. Alex Wilson, a distinguished educator and scholar renowned for her dedication to land-based learning and Two-Spirit identities. Together, they explore the fluidity of gender identities within Nova’s evocative theatrical work and Dr. Wilson’s concept of “queering the land.”

After a deeply transformative experience at a 28-day Ojibwe immersion camp in Winnipeg, MB, Nova birthed Waawaashkeshiwag Wabano to process her acute awareness of societal divides in ceremonial circles, gender disparities that permeate her personal life, and parts of her familial history—marked by the attempted erasure of Anishinaabemowin through the 60s Scoop and Residential Schools. Dr. Alex Wilson expounds upon the concept of “queering” through the prism of Nova’s characters in the play including: Noozhe’s counterpart, Kiskaw, the ebullient young male; and the venerable Elders, Aaaybe, and Esereht.

Between the two, Waawaashkeshiwag Wabano undergoes a nuanced interrogation, where themes of identity, resilience, and societal transformation converge in a captivating debate of existence and being.

Nova

The Creator initiates a conversation with animals about helping the Anishinabeg [people] adapt to Earth when they first arrive. Then, all the animals come and eventually the two-legged say, “Well, we could provide our skin for shelter and for clothing, and our flesh for nutrients and nourishment.”

And that is the backdrop of these deers’ lives, because they have a commitment to reciprocity. Noozhe questions why she even participates in the rut. Being a 38-year-old female who never really wanted children, was always like, “Oh, well, maybe I do. Is that me? Or is that my body?” And so, that inner conflict has been put into Noozhe.

Alex

Yep. Yeah.

Nova

I don’t know if you know who Lance Gilbault is? He’s in ceremony circles here in Manitoba. Myra, [our Auntie] coined this term to two-Spirit: Laramee. In the play, I have a part with the deer—during the rut—where they lose whatever sense of “themself” they had and just go mad. That was another really complex theme I struggled with because Western civilization doesn’t see animals as having a personality—so, do they even have a sense of self? I had a conversation with my cousin and he’s like, “But what about when a duck gets hit by a car, and then its partner comes and sits by the side of the road after it’s been killed? Is that not emotion?”

I was really touched by the way he explained that. We’re animals, too. We also have hormones that tell us when and who we should mate with. And so in the rut, Kiska takes on the alpha buck, Ayaabe.

Alex

Yeah, I think it’s really interesting. I’m glad you’re doing it. My work is in land-based ed, specifically “queering,” but there’s a lot of variation in what people understand it to be. When it comes to our relationship with nature, often it’s like: human versus nature. Posed in a binary kind of way. So, the challenge is that we’re always trying to queer.

When I use the term queer, I mean, “transforming poison into medicine.” It's looking at things the way things are constructed and then trying to figure out, “How did this come to be and how can we intervene in that?” That's what art does, right? It intervenes in the status quo, and in that way, it's really liberatory. So, everybody can kind of see themselves, in some way, through the art.

Alex

Alex

The fact that you’re choosing deer is interesting too. I say the deer is interesting because, I’ll tell you a story. I went to Norway and I was working with some Sami people there. They took me to one of their sacred places where they do the rock etching. You might have heard this because I told the story before.

Nova

No, I haven’t heard it!

Alex

The Sami do the same etchings as [the Opaskwayak] do in the rocks. Families have special connections and responsibilities to certain animals, similar to [the Anishinaabe clan system]. The Sami are the reindeer people. The Elder that was there was saying the waterfalls are really magical to them and they hold spiritual power in a significant way. This is their ceremonial grounds where they would signify appreciation—in terms of ritual and acknowledgement—for the reindeer. So the reindeer are like their primary importance—by the way I have permission to tell the story, they asked me to share it.

There was an anthropologist there, and the anthropologists were saying, “Well, what kind of deer is this? Is this a male or a female?” That’s the anthropological lens right there: male or female.

But the Elder said, it's called eaidánis. Eaidánis: it's either a female reindeer that hasn't had a calf, or that's not going to have a calf. Or it would be like, what we would call a trans character.

Alex

Alex

[The eaidánis] was something that every herd or family wanted, because it was seen as having spiritual significance. The bones were used for the drum, the drumstick, and then for other ceremonial things. And it was that deer that would pull the medicine person’s sleigh. This article was written in the Sami language in a journal, either the late 1800s, or the early 1900s. And it was a small story about tes eaidánis reindeer. They said that it ran so fast, it almost flew, and then it pulled the sleigh of the medicine person.

Nova

Oh, yeah?

Alex

It’s a story that every kindergarten kid understands and knows. But in the queering of it, really it’s Rudolph—you know, the queer reindeer?That story is significant, because it shows the way that we understood and related with land, and interpreted it. It was always in a non-binary way. I think that’s the challenge colonization poses: that’s the poison that we have to transform that binary thinking. And it gets entrenched into everything that we do, including the way that we explain nature. So, the impact is that people who don’t fit into that binary, or that don’t ascribe to it, are forced to act a certain way.

Nova

That was another theme I included, based on a male scientist who observed male deer when defeated so badly they exclude themselves from the rut, who were coined “shirkers.” I thought it could be a powerful commentary on the toxic male experience.

Alex

I think that’s the thing about posturing too. You can look at it in terms of relationality and maintaining good relations. Or it could be like, excluding themselves, because they were belittled.

And I mean, the whole [mainstream] hunting culture is really an example of toxic masculinity. I think there’s so many examples of deer as weak. I’ve heard that the deer theme in poetry represents a gay male. It’s seen as effeminate. And the whole hunting culture is about dominating nature—but it’s also about dominating women or dominating anything non-masculine. So you’re undoing that in the way that you’re narrating your play.

Nova

Yes!

Alex

This is one of the challenges too: when things are translated into English, or French, or Spanish—you know, like those binary languages—so then it’s automatically put into that framework.

Nova

Yeah, and I’d like to mention that Anishinaabemowin and Cree—is it Nehiyawak? Or Ininimowin?

Alex

That’s both, yep.

Nova

[Both languages] are not gendered! The verb is s/he, and you gain that context in the conversation.

Alex

I think another thing that happened in colonization is some of the terms we may use now for roles are actually people’s names. The language is very descriptive, so people’s names were descriptors. That’s why we didn’t have a word for gay in Cree, for example. But there were people who maybe [had that descriptor] in their name. And people have taken that on as meaning gay but, really, the language is descriptive, not definitive. So English, French, Spanish, those are all noun-based. And Algonquin languages like Cree and Ojibwe are verb-based. it’s just a different contextualization.

Nova

There’s been a little bit of pushback, in terms of me wanting to explore queer and non-binary themes. Some people don’t have the capacity to understand that it can be really complex, and really big. I’m like, “No! I don’t want it to be digestible! I want to be everything!” Because I know that audiences and younger people are able to consume, support, and identify with that level of complexity.

Alex

Absolutely. Yeah, some older people don’t get it because it threatens superiority, it threatens male supremacy, it threatens straight supremacy, white supremacy— any kind of queering or complexity that doesn’t mold to a binary threatens people.

Nova

When I was younger, I didn’t think I wanted kids. Then I got into youth theatre, just by chance. My mom has been a teacher for 35 years, so it was never like, unknown to me. But when I started working with them, I was like, “Oh, they’re just little people!”

Alex

Yeah, exactly.

Nova

The more I got into it, the more I understood that. [I learned] that our communities…. Really the family structure was just completely destroyed by residential schools. By living in two worlds, [I got to see] the ways that we hold our kids. It’s completely different from the way that the rest of white Canada holds their kids.

Life-giving doesn’t have to be about having kids. Like with the Sami people and Reindeer. There are roles for women like me, to help those kids grow in [different] ways.

Alex

Wow, that’s great.

Nova

I have a question as a disconnected native. How do you see that sort of revitalization happening with those of us who are trying to create new knowledge systems due to colonization and destruction? What does that look like to you?

Alex

That’s a good one. For people that create kinship structures out of necessity, I think the community-building aspect is really important. But also, I think of that iceberg analogy, where the stuff above the water is the physical manifestations. I think it’s really important for people that are trying to nourish their connections, to think about the things that are below the water. Those are the things that don’t just sever in one or two generations like values of belief systems. Even with language, it takes about five or six generations of no speakers for language to be extinguished because 80% of language is not spoken. So, if you don’t know the words that doesn’t mean you don’t know the language. If you understand nuances, you feel that. Some people call it blood memory.

Nova

(becomes visibly emotional)

Alex

Those are the things that are really important to nourish and continue to nourish. There’s underlying values that are passed on, that come from tens of thousands of years. They don’t just disappear.

Nova

The experiences that I had with [some] Elders is very gendered teachings. All while trying to be respectful of the knowledge that they held onto through years of degradation and cultural genocide.

Alex

It’s contradictory, for sure. I think that’s an example where the top of the iceberg doesn’t match the bottom and people are doing actions that don’t link to their worldview. What’s helpful for me is to remember that things that neatly align with hetero-patriarchy are passed on and reinforced. Things that don’t align with that—or things that break that apart—are dismissed and forgotten.

There’s probably millions of things like that. That have been so entrenched and then reinforced through the residential schools, which were operated on a binary. So, if [a teaching] doesn’t sit right with me, I move on and I find somebody else. I know that that’s not an option for a lot of people. But I think that is something that I always try to encourage people to do. For every Elder that says “you must do this,” you can find one that doesn’t do that.

Nova

I can see that problem… with some specific circles.

(laughs uncomfortably)

Alex

Yeah. I know…

(chuckles)

I don’t laugh at it, but I go, “Okay, here we go.”

Nova

You were talking about life-saving work… I think that’s what we do. I think that’s a really important part of what I do in theater. When I wrote this play, I was attempting to write for adults but it’s been perceived as [Theatre for Young Audiences]. But maybe I will revisit the fact that my play might be.

Alex

Yeah, absolutely.

Nova

So, I’m posturing.

(laughs)

Alex

Well, I’m glad you’re doing it.

(smiles)

Nova

Sometimes, I am too. But sometimes, I’m not.

(laughs)