Of the many portals I’ve learned to step into to call upon ancestral support, translation feels like the ricketiest gateway.

The equation to interpret a word or phrase with precise accuracy has such delicate variables. As if the temperature of the air alone could fluctuate the results.

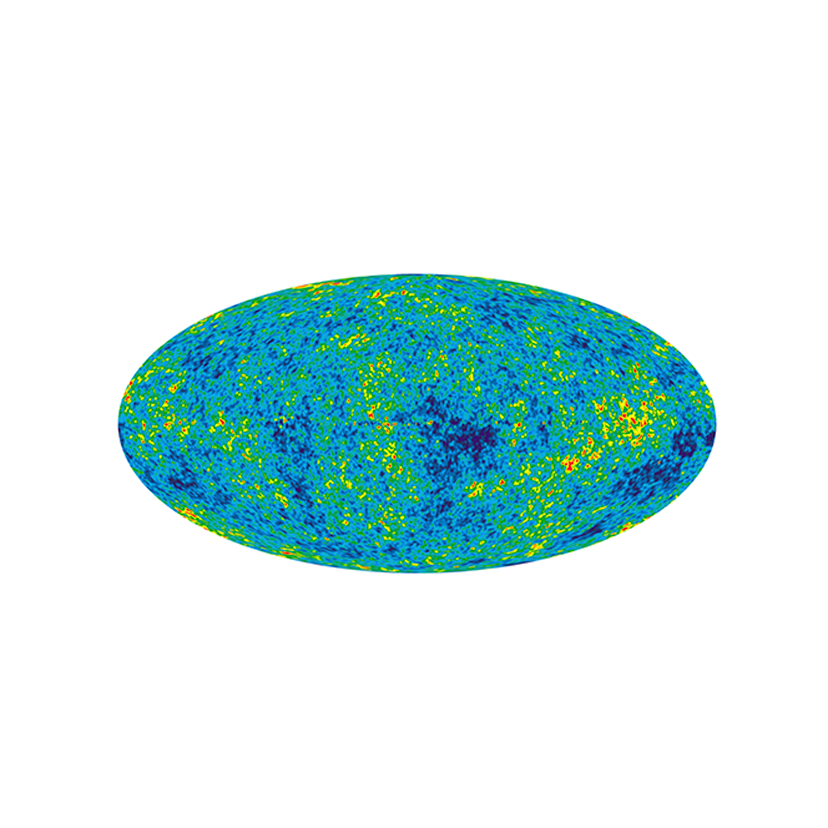

Dreams and rituals allow for abstract fluidity. We reach into these planes of existence often without our bodies: it is 11 o’clock for three straight hours; our great-great-grandmother has always known our name, the future is remembering this present.

But translation demands a certain specificity. It imports historical context, weighing 2.7 times more than the accumulation of days between its first use and the present. A method of time travel that asks you to know your destination’s coordinates down to the millisecond. And even after all this, translation is still only ever a parallel of the concept it’s trying to explain.

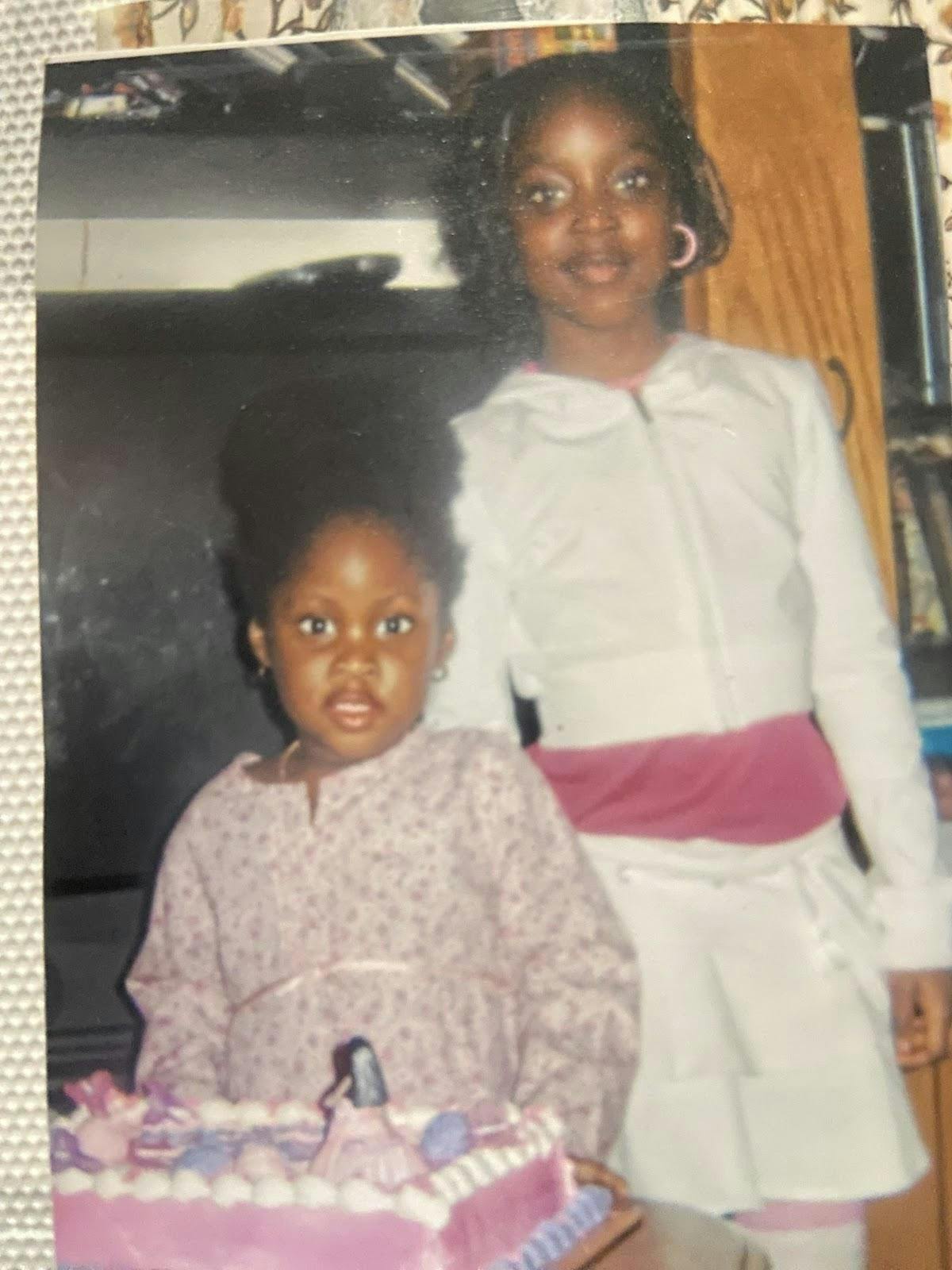

When first-generation Asian settlers and young immigrants gathered digitally to translate a letter of solidarity in support of Wet’suwet’en, it required intense calculative deliberation. For many of us with an elementary level of proficiency, online translation tools were starting points. But we soon looked to our parents to find the best interpretation for “civil unrest,” “white supremacy,” and “stolen land”—opening portals to similar times of injustice to borrow from.

Apart from being linguistically categorized as “tenseless” languages, there is very little commonality between simplified Mandarin and Bahasa Indonesia. But when my friend Chiyi Tam and I turned to each other to process this intergenerational collaboration, we found that both my mother and her father had taken issue with the same word.

Condemn: a verb here, in secularized English, that expresses public objection towards an action such as the violent invasion of Wet’suwet’en lands by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. For Chiyi’s father and my mother, this language was much “too strong.”

“Good,” I responded to my mother. “We want to speak with conviction.”

She shook her head: her eyes thinking in Javanese, her mouth struggling to find an English explanation.

“You don’t understand,” she laughed. “Only the gods have the power to condemn like this.”

Or as Chiyi’s father told her: “You are a mere mortal.”

We maintained our translations. Our letters reached our respective communities in 15 languages, including Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese. And only a few moons later, the world was halted to a standstill by three pandemics that spouted out the gears of capitalism: a global virus, an opioid crisis, and persisting, rampant anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism. Smoke began to fume from the unviable machinery of this so-called society.

As the pillars of North American imperialism began to collapse onto itself—its self-proclaimed superiority in industry, exploitative systems of labor, and colonialism repackaged as innovation—those of us who were privileged enough to, stayed indoors.

I picked up my phone and messaged Chiyi. “Do you think,” I typed from bed, the days blurring into one another. “We condemned too much?”

One debate during this intergenerational collaboration between my mother and I was which linguistic portal to open to translate the concept that our sovereignty is “inextricably linked” to the liberation of stolen land.

Merdeka: an Indonesian term which rippled across Southeast Asia, pulling from its Sanskrit roots of “rich, prosperous, and powerful” to mean freedom from colonial superpowers such as the Dutch in 1945.

When revolutionary sentiments began to gain momentum in Indonesia, our Dutch colonizers remarked that they, too, could envision a kind of “freedom” for our people—perhaps in another century or so—as a colony. In the imperialist-sanctioned imagination, our occupation was seen as a just paternalization of a people who had no idea what to do with their own land, resources, and democracy.

It was four years of armed conflict that freed us. Four whole years of militarized action, in which the defense of our homelands included the violent ousting of our colonizers from them. While the Dutch had a stronghold of cities and towns, it was ultimately the people who liberated us: our farmers, villagers, and labor-class folk.

When I call on merdeka, it not only calls on my ancestors, but also on those who seek it today including our kin in Papua who continue to fight for their freedom. Papua’s sovereignty—much like the rest of Southeast Asia, much like the Middle East, much like Indigenous People of Turtle Island—is inextricably linked to U.S. imperialism in the form of resource extractions, marionetted by Indonesian government officials who benefit from this neo-colonialism since a U.S.-backed coup where these invisible strings were tied. From Papua to Wet’suwet’en to Palestine to Congo, our solidarities against colonial capitalism are deeply interlinked.

As my mother and I held the word merdeka, it was as if there were several other voices at the table whom I struggled to hear. Soft-spoken. Challenging me to still myself. Asking me to hear beneath the hum of reality and use my peripheral vision.

Until finally, an ancestral whisper in my right ear, telling me with absolute clarity that what we were trying to translate was not just that these lands are stolen but they are to be returned.

The act of solidarity is not just in signaling that we, too, have shared oppression. It must be embodied by also acknowledging the ways that we are surviving through neo-colonialism by settling on Turtle Island which manufactures a safe distance from our own histories. To take on a responsibility of solidarity is to remember, so we know how to call for merdeka especially on lands that are not ours.

Landback wouldn’t enter mainstream conversation until later in the pandemic. As soon as I heard it, I realized the epiphanies of merdeka were preparing me to understand this solidarity.

Solidarity: A verb here to describe coming together in community with shared values, sometimes to mobilize towards a common goal. Like when Indigenous and Japanese fishermen quietly went back and forth to drop food and other supplies to the passengers of the Komagata Maru with the shared goal of keeping its brown-bodied passengers alive. Or when Indigenous Peoples tended to sick and dying Chinese workers who built the Canadian Pacific Railway to give them dignified care. Or when, following the Quebec mosque shooting, Indigenous leaders like Wab Kinew showed up to “stand with the Ummah.”

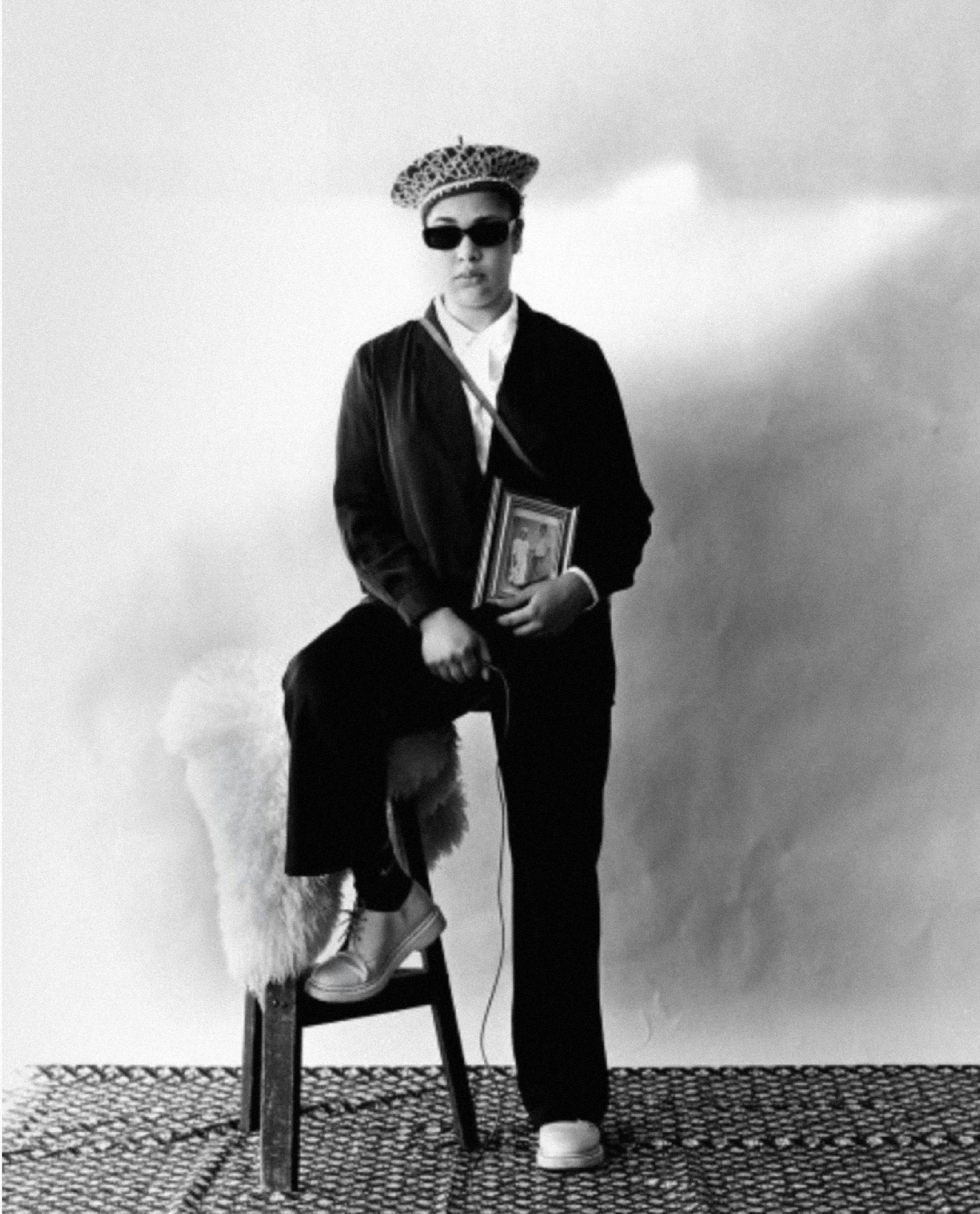

The equation to build such a trajectory includes intimate variables. It asks us to assess our current positions so that we might understand how to time-travel to a collective landing-place. Some of us are beaming from optimal conditions, while others must consider rough elements and possible sabotage. Some travel at lightspeed, while others need to recharge every other day. Some—like our trans kin who have been here before the consequences of this long twentieth century—make upgrades to their physical forms along the way.

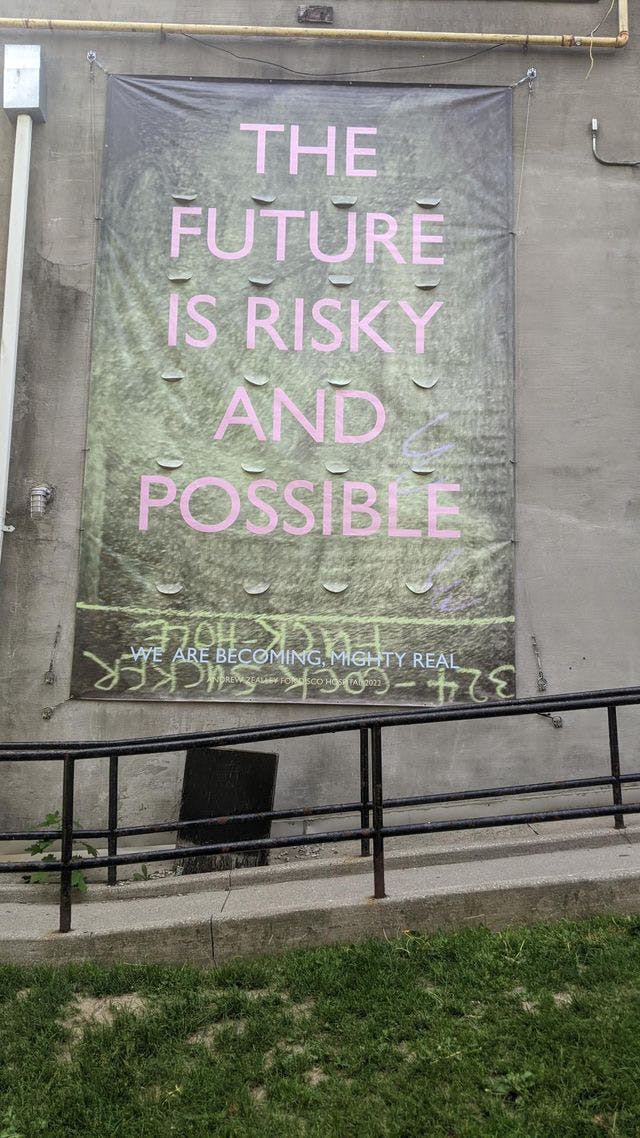

Landback is a term that has been gifted to us from its inevitable future.

Now that it has found us, we have a collective responsibility of maintaining this conversation with a future that is telling us it has already happened. We have a personal responsibility of listening to future ancestors of these soon-to-be sovereign lands. And through continued solidarity, can ensure it takes place tomorrow if we let Indigenous Peoples—of the simultaneously occurring past, present, and future—lead the way.