The exhibit opens with the inversion of an archival image.

Later, when I try to describe my experience walking through it to a friend—as an exercise in thinking through this review—I tell them that I do not know how to form myself inside it. Abraham O. Oghobase creates a jet-black print with two silhouettes. They reenact a famous image from a moment in Nigeria’s independence. Titled, Colonial Self-Portrait 05, two figures are placed against a backdrop of black ink. Negative space exposes two forms, a squat Alhaji Tafawa Balewa, Nigeria’s first Prime Minister, next to the taller James Robertson.

Both have hands raised as though to wave. Here, though, their identities are indecipherable. The artist’s statement tells us, instead, what this is, and suggests what we might be expected to feel, “a gesture of farewell and triumph”.

After, when I find the original image Oghobase is referencing, I find myself dwelling on the choice of it. Why this one? Why this moment?

In it, Balewa’s face is positioned as a side profile, upturned to gaze at Robinson’s. It is difficult to decipher what he is feeling.

In their essay, “In search of African history: the re-appropriation of photographic archives by contemporary visual artists”, art historian, Erika Nimis, delineates how contemporary African photographers turn to the archive to reclaim and make meaning. Nimis argues that the figure of the artist-historian is not new, and they work at times to produce a ‘counter/alternative history’. As a historical catalyst for this increasing turn, Nimis cites the digital revolution of the 1990’s, “which has fundamentally changed our relationship to archives, by accelerating their ‘dusting off’ and their re-appropriation, particularly in the art world.” By keeping the artist-historian in mind it becomes easier to trace what Re-Mixing African Photography as an exhibition seems to be trying to center. The final sentence of its curatorial statement signals this clearly, “presented together these artists showcase unique approaches to the photographic archive in their respective practices”. That is, the exhibition attempts to delineate how each artist straddles the line between archivist, memoirist, and historian through a selection of their works.

Given the goal of highlighting photography production with or through the archive, we begin the exhibit with Oghobase’s Colonial Self-Portrait 05.

Nigeria is a well-known country, and images from an African country’s independence serve as artefacts of its national narrative formation. The work is quite clearly of the archive at its most political, if reproduced otherwise.

Oghobase’s interaction with it is much harder to decipher—its title suggests some insertion of the artist into the artwork and in the reconstitution of the hazy outlines of the central figures. Given the print’s use of negative space, it is unclear how Oghobase mimics both the portliness of Balewa’s billowing robes and the rigid military bearing of Robinson to remake the silhouettes.

To map where his body begins, and where historical figures end. Oghobase’s practice thrives in walking these lines between the self and historical-political.

His other contributions to the exhibition continue this method of reproduction. In Colonial Self-Portrait 01, a gilded 19th/20th century photo case opens to show Oghobase as a colonial administrator in characteristic side-profile. Colonial Self-Portrait 02 and 03 which bracket an antique gun achieve the same convincing effect. While these images succeed in subverting the colonial gaze, I am less sure that coloniality itself is similarly banished. Oghobase’s goal of recasting himself in the image of Nigeria’s colonial masters is successful, but in the same way that liberal artistic projects which seek to insert Black characters into iconic historical narratives are—see Bridgerton’s Queen Charlotte, Anne Boleyn, Hamilton.

An often-successful critique of such projects is that they efface the reach of white supremacy in these historical junctures by imposing Black or racially othered bodies onto colonial and imperial power structures. Oghobase’s choice to insert himself into these moments may break the colonial gaze, but the counter-history offered here falls short of emancipatory.

Where Oghobase goes to the archive to mine sociopolitical moments, Mallory Lowe Mpoka and Kelani Abass, reach into their familial histories. Abass’s pieces: Ayajo I & II, Makohun I, and Eyonu Awure are all sourced from his larger personal series, Scrap of Evidence. Like Oghobase, Abass’s titles help suggest something about his personal approach to the archive. Ayajo, for example, is a Yoruba concept that refers to incantatory poetics of citing historical/mythical precedents, to make declarations about what is to come—that is because this happened, then this too will happen. The suggestion that the past is present, bears in the old photographs Abass recovered from his family’s archives. His paintings reproduce old family photographs.

Without this knowledge, it is hard to tell which are the actual old photographs, and which are Abass’s reproduction. Slit your eyes, tilt your head just so, and the past blurs into the present.

The pieces which make use of Abass’s father’s letterpress, do not just draw on the archive, but remake it by placing the products of different material technologies—the letterpress, the camera, the paintbrush—in conflict with one another. Given the letterpress’s own sociotechnical history, Abass’s pieces which are immediately personal, also provide an entrance into larger sociopolitical commentary. Of the three artists, Abass’s works feel incredibly narratively textured.

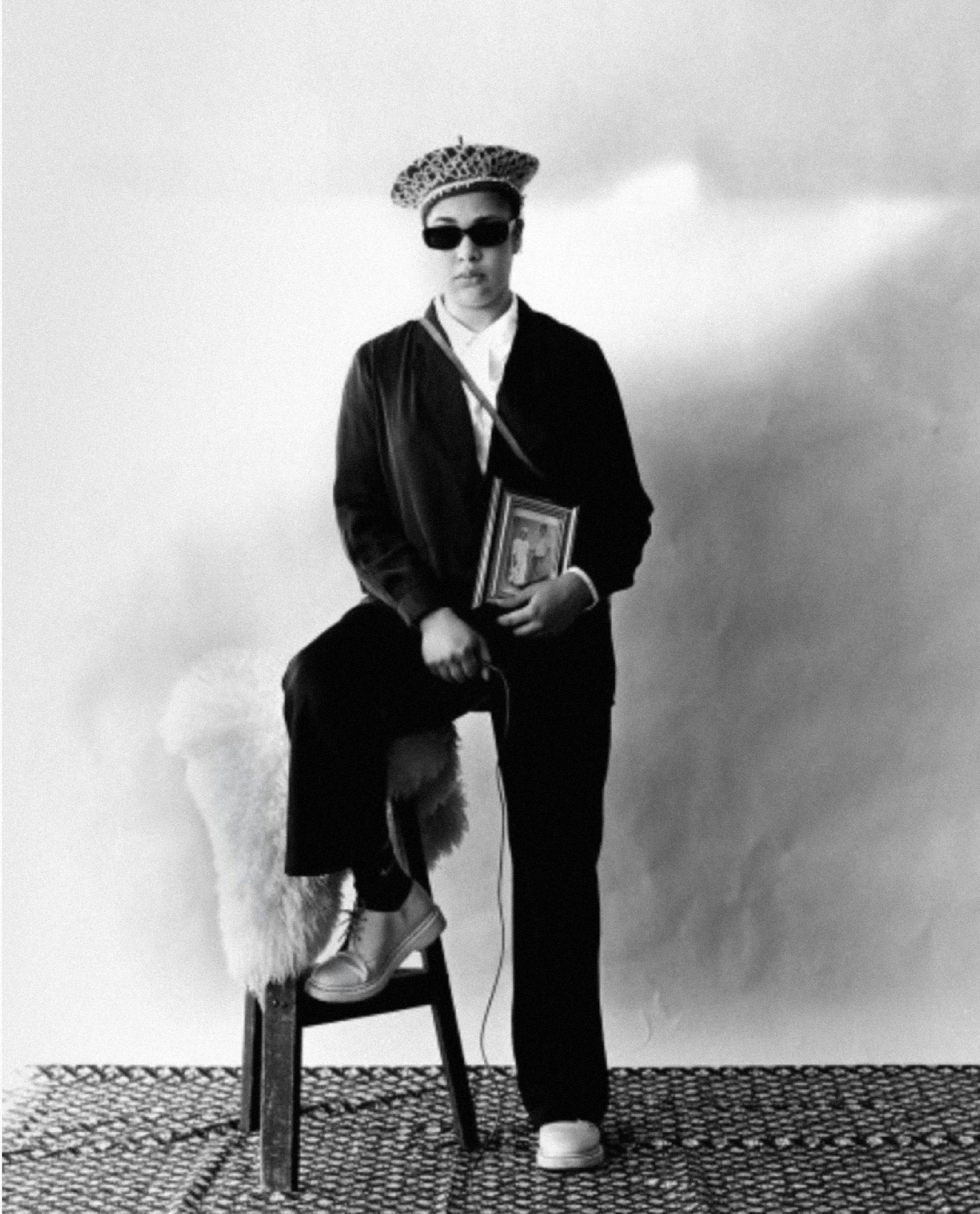

Like Abass, Mallory Lowe Mpoka also plays with the materiality of old family pictures. This is particularly borne out with her What Lives Within Us (1, 2 & 3) series. Here, however, Mpoka uses hand dyed threads from her family’s sewing workshop in Douala, Cameroon to rework her archival images. The threads’ ochre dye is drawn from the red soil of Cameroon’s highland region signifying an active and ongoing attempt of land reclamation.

Beyond their ethno-pedological implications, the threads which trail from the bottom of Mpoka’s prints also serve a utilitarian function—by weaving a mesh over the faces of Mpoka’s family members they form an anonymizing screen over their identities.

While the rationalization for this anonymization is not clarified in the artist’s statements on the pieces, the audience certainly does not need one. We lose nothing from the choice and might even gain something from it, the ability to project our own histories onto the forms of Mpoka’s family members. Where What Lives Within Us attempts to be doing something transformative with the archive, I am less sure about the inclusion of Mpoka’s diptych, The Self-Portrait Project. In these images, Mpoka stands with one leg braced upon a chair, holding an image of her father. The artist’s statements tell us that Mpoka is “attempting to perform a sense of belonging anchored in loss, commemoration and memory”. While the images are by themselves interesting, placed next to What Lives Within Us, their inclusion feels jarring and tonally inconsistent.

As an exhibit, Re-Mixing African Photography, offers important entrances into thinking about how the archive can be approached differently by artists and photographers seeking to reclaim or subvert narrative formation.

While it can be tempting to rely on the archive as a source of truth or a place to encounter our dead as authoritative oracles, Re-Mixing African Photography—perhaps inadvertently—warns us away from such follies.

Mpoka, Abass, and Oghobase’s engagements with the archive serve as a reminder of its political (re)constitution. Functioning either at the personal or the more broadly sociopolitical, each contribution points to different sensibilities and priorities in how we make sense of history. We might go to the archive to learn about our present conditions, but like so many other things, the journey/process is perhaps more important than whatever it is we hope to find.