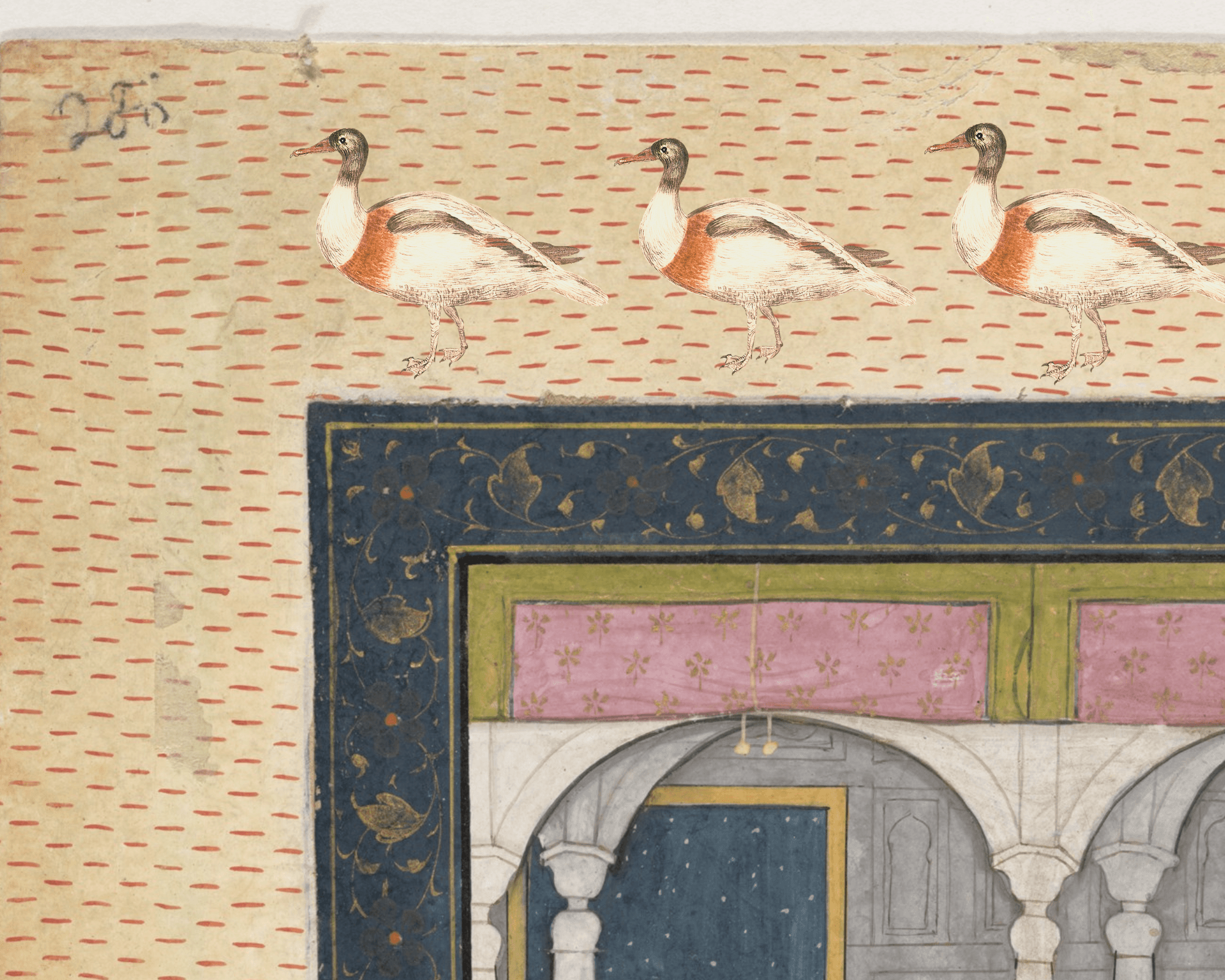

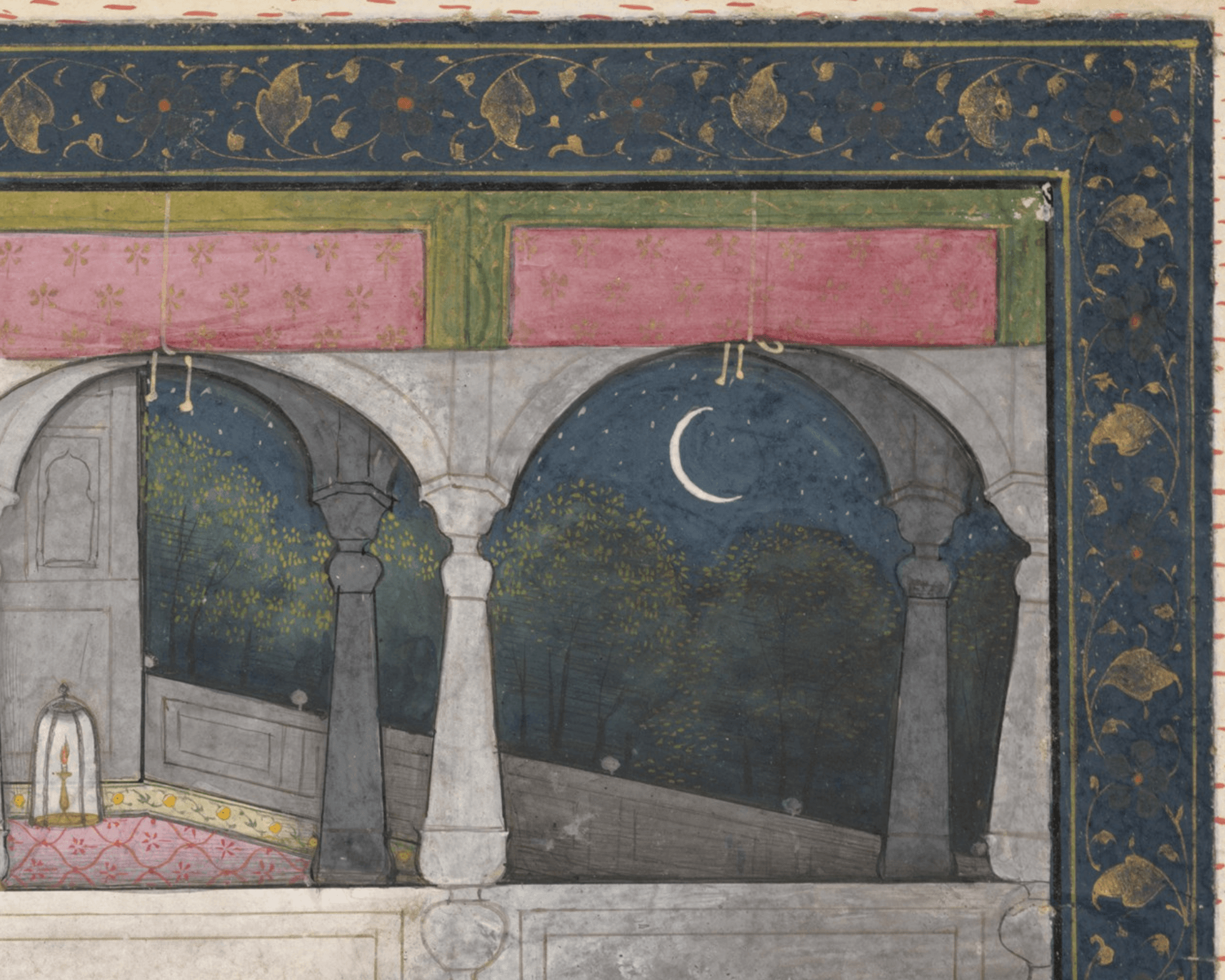

Image Credits: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Lady Holding a Sparkler, India (Punjab Hills, Kangra)

My maternal grandmother had the softest hands—large, with wide fingers and prominent lines. She was unusually tall for an Indian woman, with a husky voice and deep vibrato. Her softness was presented in the careful and deliberate coordination of her kurta with her jewellery, lipstick, and perfume, all done seated in front of her dressing table. I remember her most fondly in her batik kaftans, which she slipped into after lunch and out of just before evening tea.

We were four grandchildren, with nearly a decade between us, but she had a knack for making every one of us feel like her favourite.

We would fight to bask in the glow of her undivided attention, where she held our individuality over any other trait: inquiring about our interests, feeding our passions, and fawning over our charisma.

On the nights and school holidays we spent together, she would regale me with stories of Quick Quick, Quack Quack, and Quock Quock, three ducks who went on grand adventures, from train journeys to Kashmir and Kanoor, to bumbling caravan excursions with too many suitcases.

As the years went on, the stories became more elaborate. The ducks eventually had their own weddings, ducklings, and great-grandducklings to celebrate. My grandmother and I talked about documenting them before the memories faded, before I grew up and my parents and I immigrated to Canada; we never got around to doing that. Now, with continents between us, weekend phone calls felt like a chore. It seemed we stayed connected through a mutual yearning for closeness as comfort instead. Then, once a year, when we did visit, I would sleep in her bed just as I used to, holding those soft, silky hands until morning.

And we still had the ducks, and their endeavours seemed endless. As one of five siblings, my grandma experienced poverty that asked them to share a banana between them.

But in our story, the ducks took part in a relay race, and the winner was awarded a single prized banana. In a turn of events, they would generously split their winnings with their kin—and magically endowed with the kind consideration of each other, the banana would multiply by tens.

Quick Quick, Quack Quack, and Quock Quock were stories within stories, weaving in her childhood with dreams of abundance and hope. They were fantastical.

My mother never told me stories like these. Hers was a survivalist-driven love: involved and proud of my accomplishments with a sturdy wall when it came to affection. Where she couldn’t say or show tenderness in the way my grandmother did, she offered quality time. My interests overlapped hers in a bid for closeness, and in those moments of baking and playing piano together, I felt. I realize now that her silent disapproval when excitement for my grandmother bubbled over was, in fact, envy.

Looking back, I recognize her resentment: that we both professed love for the same woman, but one of us had a potential connection that was never actualized. It’s something I see in myself when I witness my son’s unconditional love for his grandmother.

My mum has now entered this magical phase of her life, where just the mention of her name elicits shrieks of delight and wild excitement from her grandchild. Now, as a teller of new Quick Quick, Quack Quack, Quock Quock tales to my son, I’m beginning to deal with what Bethany Webster calls the mother wound—legacies of dysfunction and pain from women who endured patriarchal cultures. As descendents of a military family, I see rejection and pain that are so intrinsically linked: my grandmother being left a widow with two teenagers after my grandfather’s health complications; my mum and her sister’s adoption in an India that was filled (and still is) with the stigma of caste. These rip through the seams of my family, pulling at the threads that should bind us.

But this commitment to look at generational trauma and work towards inner understanding and healing feels collective. I’m being initiated into the realm of holding the heaviness of mother-daughter toxicity for the many generations before me.

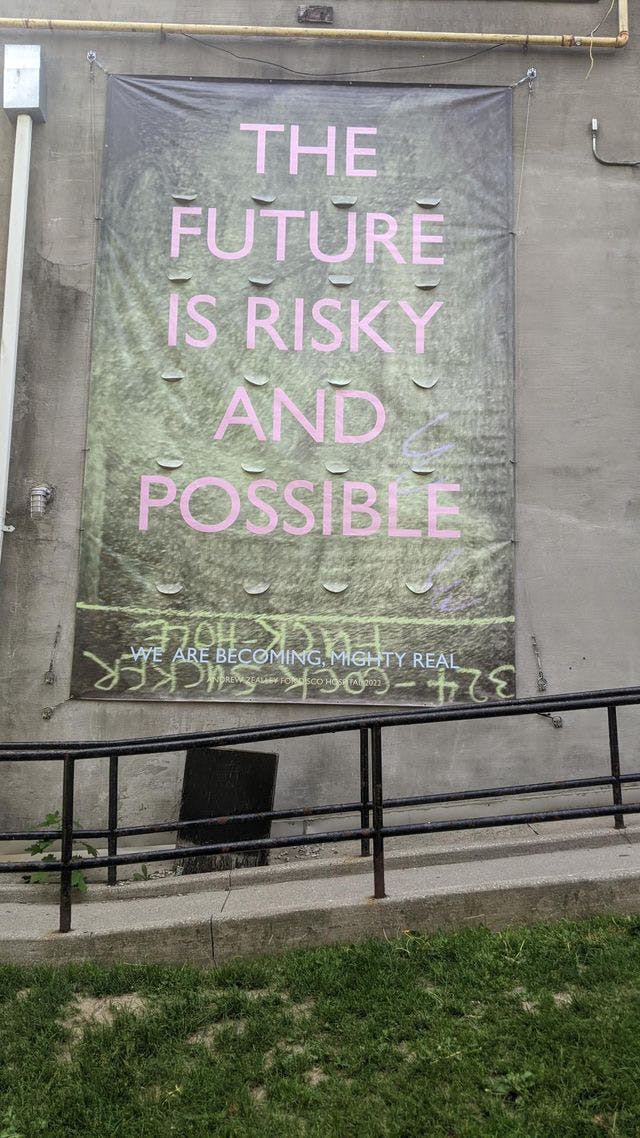

I’m taking deep sighs, inviting it all in and letting it wash over me as a kind of ancestral medicine. Part of the ritual is accepting some days are light-hearted and full of hope, while other days yearn for bedtime.

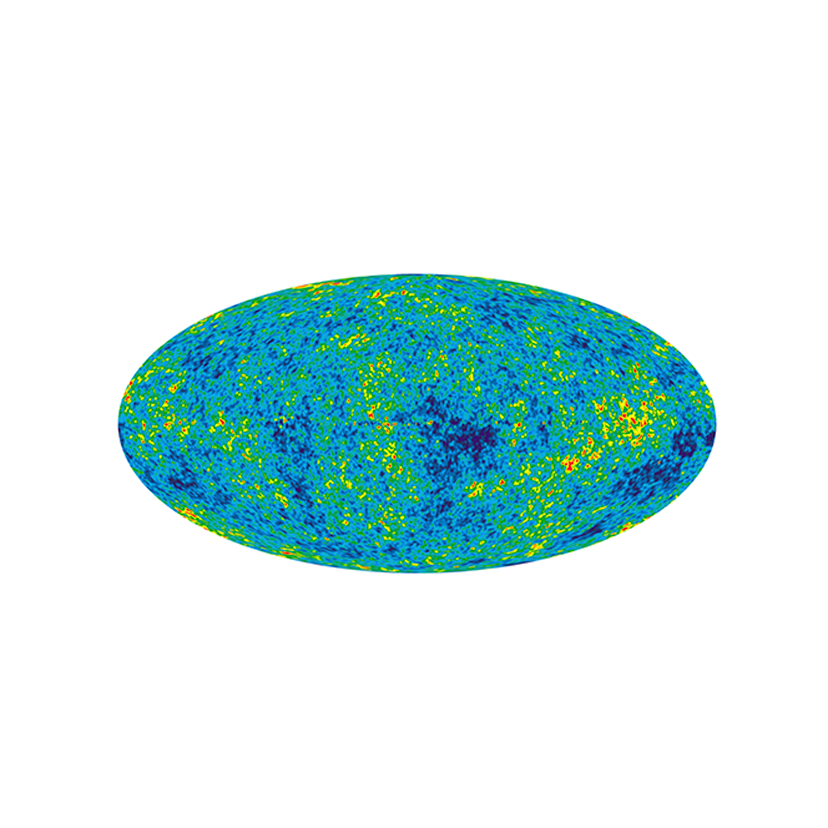

Last night, Quick Quick, Quack Quack, and Quock Quock went to the moon. I overheard my husband flying my childhood ducks on a rocketship into space, kitted out with moon boots and regulated helmets. Despite vastly different upbringings, my partner—this grounding presence who effortlessly pours patience and sees the light in me despite my shadows—embeds new stories within these stories : weaving in our memories, vacations, and love. The giddy joy I experience eavesdropping is therapeutic. The healing power of time and stories serves as a bridge between my own childhood and my son’s. My grandmother would have loved the absurdity.

These days I find myself seeking out stories in my maternal line, seeing them as unique patches before stitching them together. The whole of these many and varied pieces is greater than the sum of its parts.

As I learn to hold space for my mum and her maternal shortcomings, I’m adding my own precious scraps with new textures and colours; I’m adding my own people; I’m creating a story different from the one I was once told; and my quilt grows in size.

And like a running stitch, the ducks continue to tell a parallel tale—and it is fantastical.